Bath, Somerset

Up to 1834

A parliamentary report of 1777 recorded parish workhouses in operation at Bath—St James (for up to 35 inmates), Bath—Saints Peter and Paul (35), Lincomb and Widcomb (10), Swanswick (8), Walcot (100), and Weston (10).

Eden, in his 1797 survey of the poor in England, reported:

Walcot in the city of Bath maintains the poor partly in a Workhouse and partly at home. At present (Oct. 1795) 101 are in the workhouse. The contractor receives an allowance of 2s. 6d a week for each person, besides an annual allowance of £40. In consideration of the dearness of provisions, the parish has lately given him an addition of six guineas a week. He provides every necessary wanted in the Workhouse. The parish pay 294 regular out-pensioners. About 10 or 12 receive casual relief. Settlements are gained principally by service. There are only two farms. Rent of land, 50s. to 60s. an acre. Land tax under 1d. in the pound. There are several friendly societies, but no information could be obtained about them. Butcher's meat costs 4d. to 5d. per lb. labourer's wages, 14d. to 18d. a day. Four sixpenny rates on the net rent were collected in 1794, each of £718 4s. 9d., but £200 remains unexpended. The rates for two or three years back have been nearly the same. A considerable part of Bath stands in this parish, and most of the houses have been built in the past 50 years.

The Walcot parish workhouse was located at the south side of the London Road and was rebuilt in 1828. It still stands and the building is now used as retail premises.

Walcot former parish workhouse, 2004.

© Peter Higginbotham.

In 1837, the parish of Walcot was involved in a much publicised settlement dispute. A man called William Withers was travelling from Bristol to London when he became stricken with severe rheumatism and had to spend six weeks in the Walcot workhouse which was still in use prior to the opening of the new Union workhouse. Eventually, Walcot decided to remove him to Clerkenwell and at 6pm he was put aboard the outside of a coach open to the wind and snow. After seven hours, at the halfway point at Newbury, he had to be lifted off the coach and revived with a little brandy and water. When he arrived in Clerkenwell, he had lost virtually all use of his hands and feet and was a bedridden invalid. A court then decided that, due to a technicality, his removal from Walcot had been illegal. However, to rectify matters, he would have to return there for removal proceedings to be reconducted. In the meantime, Clerkenwell could pass on the cost of Withers' upkeep to Walcot, and so treated him like a king, to the tune of five shillings a week. The ratepayers of Walcot had had to stump up £500 in legal costs plus the initial removal expenses and the cost of his keep until he was fit to return to Bath whereupon he could be removed again — legally — back to London.

The parish of Freshford had a workhouse on Stanley Hill. In April 1803, the building was destroyed by fire.

Batheaston had a parish workhouse building on London Road dating from 1821. Another small parish house stood on Fosse Lane.

Batheaston former London Road parish workhouse, 2004.

© Peter Higginbotham.

In 1815, a local Act was passed by parliament for building a new church and workhouse in the parish of Bathwick. The Act (which was deficient and had to be amended by a subsequent Act in 1817) provided for the expenditure of £4,000 on the new church and £1,000 on the workhouse. The workhouse is said to have been located in part of what is now Sydney Buildings.

Bath former Sydney Buildings parish workhouse, 2004.

© Peter Higginbotham.

After 1834

Bath Poor Law Union was formed on 28th March 1836. Its operation was overseen by an elected Board of Guardians, 41 in number, representing its 24 constituent parishes as listed below (figures in brackets indicate numbers of Guardians if more than one):

Somerset: Bath—St James (3), Bath—St Michael (2), Bath—St Peter & St Paul (2); Bath—Walcot (8), Bath Hampton, Bath Easton [Batheaston], Bath Ford [Bathford], Bathwick (2), Charlcombe, Charterhouse Hinton, Claverton, Combhay, Dunkerton, English Combe, Langridge, Lyncombe &, Widcombe (4), Monkton Combe, St Catherine, South Stoke, Swanswick, Twerton or Twiverton (2), Wellow, Weston (2), Woolley. Later Additions: Freshford (1883)

The population falling within the union at the 1831 census had been 64,230 with parishes ranging in size from Wooley (population 104) to the city of Bath itself (38,063). The average annual poor-rate expenditure for the period 1832-35 had been £19,928 or 6s.2d. per head.

The new workhouse was built 1836-8 to a design by Sampson Kempthorne on a site to the south of the city at Coombe Down between Warminster Road (now Midford Road) and Frome Road. It was designed to accommodate 600 people and cost around £12,300. Its was based around one of Kempthorne's Y-shaped designs. The buildings, mostly of three storeys, were faced with Bath stone. The site layout can be seen on the 1902 map below.

Bath workhouse site, 1902.

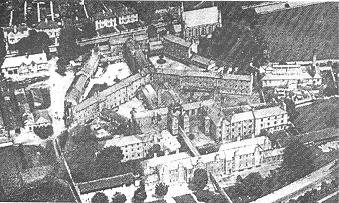

An early twentieth century aerial view from the south-west gives a good impression of the size of the site. The areas between the arms of the "Y" formed enclosed yards for the various classes of inmate.

Bath, early 20th century.

The entrance and administrative block faced onto Warminster Road. This contained offices for the porter, relieving officer and chaplain.

Bath workhouse front block, 2000.

© Peter Higginbotham.

From the centre rear of this runs one arm of the "Y" which contained further offices, the Guardians' board-room, a provisions store. The central hub of the "Y" contained the workhouse kitchens. The western arm contained men's day room, dormitories etc. while the southern arm contained the women's accommodation.

Bath women's block from south, 2000.

© Peter Higginbotham.

To the south of the "Y" stand some additional accommodation blocks which were added to the original buildings at a later date. Further south, facing on to the Frome Road is an infirmary block.

Bath workhouse from south, 2000.

© Peter Higginbotham.

At the north of the site, now home to the hospital's buildings department, is the original workhouse bakery which employed the services of two full-time bakers. In addition to producing its own bread, the workhouse had five acres of vegetable gardens, orchards and a pigsty all looked after by the inmates. The workhouse also had its own shoe-makers's shop.

Bath workhouse bakery, 2000.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Originally, a room in the north-eastern arm of the "Y" would have served as a chapel. However, a separate chapel bearing the date 1846 was erected to the east of the main building. Its foundation stone was laid at a ceremony on 10th February 1843 by Tristan Whitter, Esq. M.D., with the workhouse children singing a hymn. The remarkable work of the chapel's builder is commemorated by a plaque on the wall:

"To record the services of John Plass, an inmate of the workhouse who, at the age of 78, working with much zeal and industry, laid all the stone of this building. Died 5th June 1849 aged 82, and buried in the adjoining ground."

In 1924, the chapel was dedicated to St Martin of Tours who, it is said, cut his military cloak in half, giving one part to comfort a beggar.

Bath workhouse chapel, 2000.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Bath workhouse appears to have suffered from overcrowding — by 1845, a total of 758 adults and 374 children were crammed into accommodation designed for 600 (Dunbar Cross, 1989).

Despite the cramped conditions, education of the workhouse children seems to have achieved some successful results. As well as the standard three daily hours of schooling required by law, the Guardians decided that every child should acquire basic skills in knitting, tailoring and shoe-making. The boys also learnt hair-cutting. In 1846, the Inspector of Schools, Mr Clarke, reported that he had spent three hours of great satisfaction in the schools of Bath Union Workhouse. The boys were smart, intelligent and well-informed. The girls also deserved praise except in their arithmetic.

The younger children did not always fare so well as indicated by the Visitor's report of 21st January 1847:

In 1894, the British Medical Journal set up a "commission" to investigate conditions in provincial workhouses and their infirmaries. Following a visit to Bath, the commission's report catalogued the establishments' shortcomings. The ground-floor wards in the infirmary were "dark and squalid"; the staircases were steep and narrow; the water supply was inadequate, with all hot water for the infirmary needing to be carried from a boiler across a courtyard; no hot water was available at night except by boiling a kettle. The infirmary's sole night nurse up to 230 beds to supervise, and the medical officer lived a mile away and was not in telephone contact with the workhouse. The commission strongly recommended that the nursing staff be increased and placed under the control of a qualified nursing matron. It was also suggested that new infirmary buildings be provided since "no amount of patching and remodelling would overcome the stubborn facts of structure". Further details are available in the full report.

For many elderly paupers, the workhouse was where they would spend their final days. Most of the workhouse dead were buried in unmarked graves on the other side of the Frome Road, opposite the Red Lion — a total of 4,289 between 1839 and 1899.

In 1905, the workhouse became known as Frome Road House, and later as Frome Road House Poor Law Institution. During the Second World War, an EMS (Emergency Medical Service) hospital operated on the workhouse site. In 1948, with the inauguration of the National Health Service, it became St Martin's Hospital.

Scattered Homes

For its pauper children, Bath adopted a scattered homes scheme, which by 1919 comprised six homes in and around the city: Five Way House, Fosse Lane, Batheaston; 15 Lambridge Place; 1 Larkhall Place; 3-4 Butty Piece Cottages, Park Street Mews, Portland Road; 32 Thomas Street; and 1-2 Bridge Road, Twerton. The total capacity of the homes was then 120 places.

Five Way House, Batheaston, 2013.

© Peter Higginbotham.

15 Lambridge Place, Bath, 2013.

© Peter Higginbotham.

1 Larkhall Place, Bath, 2013.

© Peter Higginbotham.

A headquarters home known as Three Ways House (later Threeways Cottages) was located near the workhouse, at the south side of the Frome Road. The headquarters home provided a receiving home for new arrivals and an administrative centre for the scheme.

Bath Headquarters Homes site, 1933.

Three Ways House, Bath, 2013.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Staff

Inmates

Records

Note: many repositories impose a closure period of up to 100 years for records identifying individuals. Before travelling a long distance, always check that the records you want to consult will be available.

- Bath and North East Somerset Record Office, Guildhall, High Street, Bath BA1 5AW. A wide variety of records survives including: Guardians' minute books (1836-1930); Workhouse admissions (1914-1934); Baptisms (1847-1922); burials (1847-99); Bastardy order registers (1844-85); Relief order books (1886-1928); Ledgers (1836-1909); Cottage Homes administrative records; etc.

Bibliography

Links

Unless otherwise indicated, this page () is copyright Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.