St Martin-in-the-Fields, Middlesex, London

Up to 1834

St Martin's Vestry erected a workhouse in around 1665 in St Martin's Churchyard. In 1672, the parish authorities were found guilty of the "scandalous offence" of letting the vaults as wine cellars, possibly by the parish-owned King's head alehouse in St Martin's Lane. The Bishop of London ordered an end to this "prophane use" and that the vaults should be "solely made use of for the burying and interring of Dead bodies." The workhouse appears to have been little used and in 1683 it was let until such time as demand justified the parish opening a new workhouse. This seems to have happened in 1724 when £607-10s. was allocated for a new establishment.

In 1732, An Account of Several Workhouses... included the following report on St Martin in the Fields:

They neither Brew nor Bake in the House, being furnished with the Convenience of having in the Neighbourhood

Beer by the Barrel at - 00 06 00

Baking a large Pudding for 00 00 01 and

Good Bread at the Market Price.

A Committee of the Vestry inspect the House Accounts every Fortnight and when approved sign them. The first Wednesday after every Quarter Day, all the Fortnights Accounts for the preceeding Quarter, are again examined, and passed by a Quarterly Meeting of the Vestry.

The Expence of the House is generally 5 or 600 Pounds a Quarter.

The Profits of the Labour is kept in a Book by itself, and all the Gains applied towards buying more Materials for employing the Poor.

A Surgeon attends the House gratis, and an Apothecary furnishes them Annually with Advice and Medicines at a moderate Rate.

Three sides of the building had street frontages — Hemmings Row at the north, Duke's Court at the south, and Castle Street at the east, and at various times all of these were given as its name or location.

The premises, which were enlarged in 1772, also incorporated a parish charity school originally endowed by Archbishop Tenison (vicar of the parish from 1680-92). A parliamentary report of 1777 recorded that the workhouse could then accommodate 700 people, making it one of the largest in the country.

In 1797, St Martin in the Fields was the subject of a report in Eden's survey of the state of the poor in England:

Early in the year 1796, when flour was 12s. a bushel, the churchwardens and overseers of the Poor came to a resolution to substitute rice instead of flour for puddings and other uses in the house. The following table will show the difference of expense in the two articles per week: Plum pudding—4 bush. flour, £2 8s. ; 4 bush. barley at 7s., £1 8s. ; 42lbs. raisins, 12s. ; 30lbs. suet at 6d., 15s. ; 8 gallons milk at 1s. 4d., 10s. 8d. ; allspice and ginger, 3s. 9d. Total, £5 17s. 5d. Rice pudding—l00lbs rice, 19s. ; 18 gallons milk, £1 4s. ; 14lbs. sugar, 8s. 2d. ; 10lbs. butter, 6s. 8d. ; 1lb. spices, 3s. 6d. Total, £3 1s. 4d. Difference in cost, £2 16s. 1d. This quantity will dine 600 people. Admitted into the house in the year 1795-6, 797 persons. Discharged, 710 persons. Died, 112 persons.

After 1834

On 29th April, 1835, St Martin's became a Poor Law Parish under the 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act. Its poor relief activities were then overseen by an elected Board of Guardians, 24 in number.

The layout of the workhouse is shown on the 1871 map below. As can be seen, the workhouse was built around an old and apparently well-stocked burial ground.

St Martin's workhouse site, 1871.

By the 1860s, conditions in the workhouse were appalling. St Martin's was the subject of one of the detailed reports that were published in 1865 in the medical journal The Lancet. Extracts from the report are presented below.

The faults which are evident in the arrangement of the sick wards are repeated throughout the house. Like most of the metropolitan workhouses, St. Martin has a population which, without reckoning the nominal "sick," who are housed in the infirmary, really consists almost entirely of diseased or infirm persons who require more or less of medical attendance. Thus in June last, on the occasion of our first visit, out of a total population of 368, 114 were entered as "sick ;" but there was a total of 256 names on the medical relief books as requiring extra diets, and besides these there were numerous other patients. In short, the condition of the inmates generally is such as demands particular attention to ventilation, and this is precisely the subject which is treated with the most reckless neglect. This fault is universal, ward after ward, which we carefully measured, being greatly below even the Poor-law standard as to the allowance of cubic space ; and the attempts at subsidiary ventilation which have from time to time been made are ridiculous. The lying-in-ward, the nursery, and the casual wards, may be selected as examples—the badness of the arrangements following a crescendo scale. The lyingin department is contained in a single ward on the third story of the main block of the workhouse. The room is awkwardly shaped, a large piece being taken out of its width, at the lower end, by a projection of the wall : but as there are seldom more than six inmates, it happens that there is a much snore liberal allowance of cubic space than in most of the other wards. This advantage, however, is utterly neutralized by the fact that there are but two windows and one ventilator : the windows are blocked up by massive wooden screens, which the sapience of the guardians has devised in order to protect the modesty of the gentleman-paupers in the court-yard from possible demonstrations on the part of the unfortunate creatures who are expecting or recovering from their confinement ; the one ventilator is a large square hole in the wall, leading into a shaft which goes out through the roof, and the only conceivable use of it is to pour a down-draught of cold air upon the luckless occupant of the labour bed, which is conveniently placed below it. At night, of course, the windows are snugly closed and the flap of the ventilator turned up, if it be anything like cold weather; and we observed that the nurse had, with careful forethought, papered over some meagre ventilating slits in the window panes which might still have permitted some trifling ventilation to go on. With the atmosphere thus produced, and with the additional infliction of being forced to hear the groans of any patient who may be actually in labour, the inmates of the St. Martin's lying-in ward endure a state of things which we suppose no man of the commonest sense or feeling could bear to inflict, unless he were a "guardian of the poor." After all, there is a certain feeling of the ludicrous inspired by the stupidity of these arrangements for it does not appear that they have yet provoked any such tragical Nemesis as the outbreak of a puerperal fever. It is a very different matter, however, when we come to consider the results of the neglect of ventilation in the nursery. The allowance of cubic space in this apartment is much less ample than in the lying-in ward, and the subsidiary arrangements for ventilation are of the same kind ; the atmosphere is extremely foul. Into this room, a few months since, there accidentally came a woman bearing with her the infection of measles, and the result of this, in such a vitiated atmosphere, was a most disastrous outbreak of the disease, in which eight children died : the malady assumed a very virulent type, which must doubtless be referred to the sanitary deficiencies of the apartment. As for the tramp-wards, the only epithet which call be applied to them is — "abominable." The male tramp-ward, in particular, struck us with horrified disgust. We scarcely had a fair glance at it on the occasion of our first visit, being accompanied by the visiting committee (for whose edification, by the way, we strongly suspect it had been furbished up in an unusual manner) ; but a few days since we revisited it, and the impression produced on our minds is that we have seldom seen such a villanous hole. It is situated completely underground, and is approached by an almost perpendicular flight of stone steps, leading to a grated iron door, through which one passes into an ill-smelling watercloset, which forms the antechamber of messieurs the tramps. The apartment at the moment of our entrance (about mid-day) was being ventilated and cleaned by a very nasty-looking warder. The ventilation-business seemed difficult, for there is but one window, closely grated, to this apartment, in which some sixteen or twenty people sleep, and that is quite close up to the watercloset end. From the other part of the room, in which the beds (or shelves) for the tramps are situated, and in which the nasty-looking man was making feeble movements with a brush, there arose a concentrated vagrantstink which fairly drove us out, not without threatenings of sickness. The bath-room, in which the "casuals" are facetiously supposed to wash before retiring to rest, is a still-more dungeon-like place; or rather (to use a less dignified and more appropriate phrase) it is like a very bad beer-cellar, through the obscurity of which one may dimly perceive a tin bath, while one's nose is assaulted by new and more dreadful stench. Both bath-room and sleeping-room were extremely dirty ; and considering that the allowance of cubic space for each sleeper is but 294 feet under the most favourable circumstances, it is really a marvel that typhus does not spontaneously arise among the temporary inhabitants of this disreputable ward. If any of the tramps fall sick, they are taken up into a miserable ward in a onestoried building at the east end of the premises, and closely adjoining the dead-house, in which they are greatly over-crowded when the place happens to be full, and the bedfurniture of which is squalid and mean.

As might be expected in an establishment the managers of which are so neglectful of such important matters as ventilation and the supply of proper water-closets, the nursing arrangements are very insufficient. There is but one paid nurse, a very intelligent and active woman, who confesses that it is impossible for her, even with the most fatiguing exertions, to keep up a really efficient supervision of the house. Her apartment is placed next to the lying-in ward, and far away from the infirmary proper. There is a pauper day-nurse to each ward, and extra nurses are supplied for night duty. The master, who is a very active and conscientious officer, does his best to superintend the ward management generally ; and he reports that, in his opinion, the pauper nurses, on the whole, do their duty fairly. But we saw great reason to doubt whether this is the case with regard to the administration of medicines, nor could this be expected, by those who know hospital requirements, from the character and appearance of these females. A good instance of their inefficiency is supplied by the way in which they manage, or rather neglect, the few imbecile patients in the house (who, by the way, are scattered through several different wards) ; these poor creatures have no suitable employment at all, and it is clear that the attendants of the wards in which they may happen to be have no notion of any such management as might tend to improve their mental state. It must be confessed, however, that the guardians are primarily to blame in this matter, since they have organized no arrangements calculated to be useful to their insane inmates, and seem to consider them as of no consequence.

The medical attendance on the sick appears to be performed in an exemplary manner by Mr. Skegg, the medical officer ; far better, indeed, than the guardians have any right to expect, seeing that they give him only the miserable salary of 120l. a year, and out of this sum require him to find drugs of all kinds, and to dispense them.

The outcry that The Lancet articles provoked was a significant factor leading to the passing of the Metropolitan Poor Act in 1867. The Act introduced major changes in the provision of care for London's sick poor and also resulted in the creation of the Metropolitan Asylums Board.

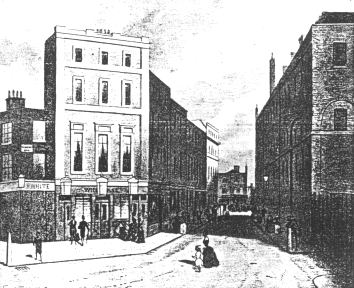

In 1868, St Martin's parish was incorporated into the Strand Poor Law Union. The St Martin's workhouse was demolished in 1871 to make way for an extension to the National Gallery.

St Martin's workhouse (at right) from north-west.

Records

Note: many repositories impose a closure period of up to 100 years for records identifying individuals. Before travelling a long distance, always check that the records you want to consult will be available.

- City of Westminster Archives Centre, 10 St Ann's Street, London SW1P 2DE. Extensive holdings include: Churchwardens' and overseers' minutes (1755-64,1772-1892, indexed 1774-84, 1856-63); List of churchwardens and overseers (1755-1856, indexed); Churchwardens' and overseers' accounts (1598-1844); Lists of the poor in churchwardens' accounts (1741-42,1758-61); Workhouse building minutes (1770-83); Workhouse sub-committee reports (1817-22); Workhouse admission and discharge registers (1725-29, 1741-1846); Workhouse admission registers (1818-33); Workhouse day books including admissions and discharges (1737-1826); Workhouse selling books [forfeits of food in return for day out] (1826-35); Workhouse building accounts (1770-1830); Workhouse accounts (1725-50); List of lunatics in workhouse day book (1744-8); Lists of nurses and children (1762-3,1768-9,1779-95); etc.

-

The

Ancestry UK

website has two collections of London workhouse records (both name searchable):

- Westminster workhouse records are available on FindMyPast, .

- London Metropolitan Archives, 40 Northampton Road, London EC1R OHB. Holdings for St Martin-in-the-Fields workhouse: Admissions and discharges (1824-70); Births and deaths (1848-57); etc. Other holdings: Guardians' minute books (1836-68).

Bibliography

- Higginbotham, Peter Workhouses of London and the South East (2019)

- Poor Law Records (Information Sheet 13, Westminster City Archives, 2003).

- The Lancet, September 9, 1865.

Links

- The Pauper Lives in Georgian London website includes much information on the workhouse and on some of the individual inmates, plus some images of the building.

Unless otherwise indicated, this page () is copyright Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.