St Asaph, Flintshire

Up to 1834

No information.

After 1834

St Asaph Poor Law Union was formed on 10th April, 1837. Its operation was overseen by an elected Board of Guardians, 24 in number, representing its 16 constituent parishes as listed below (figures in brackets indicate numbers of Guardians if more than one):

Denbigh: Abergele (2), Bettws yn Rhos, Bodfary (in the counties of Denbigh and Flint), Cwn or Combe, Denbigh (4), Dremeirchion, Dyserth, Henllan (2), Llandulas, Llanfair Talhaiarn, Llansannan, Llanyfydd, Meliden with Prestatyn, Rhuddlan and Rhyl (2), St Asaph (3), St George.

The population falling within the Union at the 1831 census had been 22,017 with parishes ranging in size from Llandulas (population 307) to Denbigh (3,786). The average annual poor-rate expenditure for the period 1834-36 had been £11,431 or10s.5d. per head.

St Asaph Union workhouse was erected in 1838-9 on the east side of the Denbigh Road to the south of St Asaph. The Poor Law Commissioners authorised an expenditure of £5,499.16s.8d. on construction of the building which was intended to accommodate 200 inmates. Its location and layout in 1914 are shown on the map below.

St Asaph workhouse site, 1914

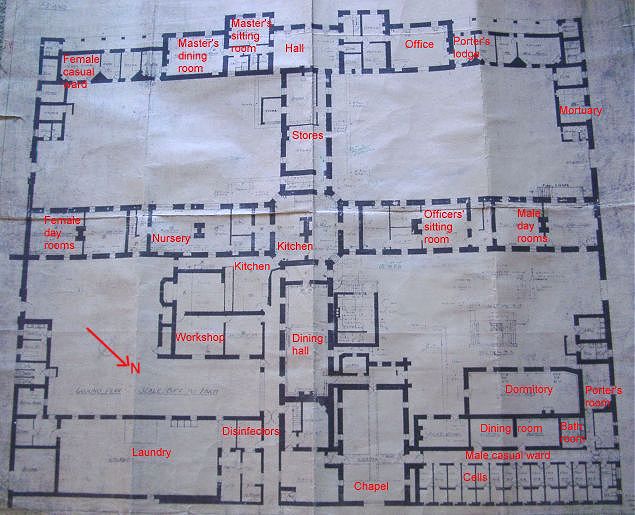

The workhouse design, by John Welch, followed the popular cruciform or "square" layout with separate accommodation wings for the different classes of inmate (male/female, infirm/able-bodied etc.) radiating from a central hub.

The entrance at the south-west comprised an entrance hall flanked by the Master's quarters to one side, and the porter's lodge and offices to the other.

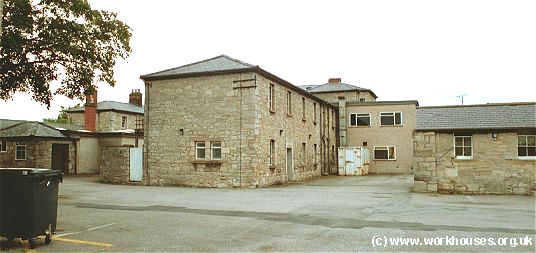

St Asaph workhouse from the south-west, 2000.

© Peter Higginbotham.

St Asaph workhouse entrance block from the west, 2000.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Males were accommodated at the north and west of the site, with females at the south and east. The female side included a nursery and laundry.

St Asaph workhouse south-east wing from the east, 2000.

© Peter Higginbotham.

St Asaph workhouse central hub and nursery from the south, 2000.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The dining-hall, at the rear of the hub, linked to the north-east side of the workhouse and included a laundry, bakehouse, mortuary and refractory cells, where miscreants could be placed

In 1890, a chapel was erected next to the dining-hall. In 1903-5, a separate pavilion-plan infirmary was built to the rear of the workhouse and later linked to it via a corridor. The laying of the infirmary's foundation stone was reported by The Builder:

St Asaph workhouse 1905 Infirmary from the north-west

© Peter Higginbotham.

In 1912, vagrant cells were constructed on the north-east side of the workhouse, adjacent to the chapel . A small female casual ward lay at the southern corner of the workhouse.

St Asaph workhouse chapel and male vagrants' cells from the north, 2000.

© Peter Higginbotham.

A ground-floor plan of the building from around 1926 is shown below (click on the picture for an enlarged version).

St Asaph workhouse ground-floor plan, c. 1926.

courtesy of Huw Thomas

In 1847, the five-year old orphan John Rowlands became an inmate of the workhouse. In later life in the USA, Rowlands adopted the name Henry Morton Stanley and, as a journalist for the New York Herald, tracked down the missing explorer Dr David Livingstone, greeting him with the famous words "Dr Livingstone, I presume?"

Stanley had been placed in the workhouse by his foster parents Richard and Jenny Price after his uncles had refused to pay them an increase in the boy's maintenance. Stanley's autobiography vividly recalls his memories of St Asaph workhouse.

The way seemed interminable and tedious, but he did his best to relieve my fatigue with false cajolings and treacherous endearments. At last Dick set me down from his shoulders before an immense stone building, and, passing through tall iron gates, he pulled at a bell, which I could hear clanging noisily in the distant interior. A sombre-faced stranger appeared at the door, who, despite my remonstrances, seized me by the hand, and drew me within, while Dick tried to sooth my fears with glib promises that he was only going to bring Aunt Mary to me. The door closed on him, and, with the echoing sound, I experienced for the first time the awful feeling of utter desolateness.

The great building with the iron gates and innumerable windows, into which I had been so treacherously taken, was the St. Asaph Union Workhouse. It is an institution to which the aged poor and superfluous children of that parish are taken, to relieve the respectabilities of the obnoxious sight of extreme poverty, and because civilisation knows no better method of disposing of the infirm and helpless than by imprisoning them within its walls.

Once within, the aged are subjected to stern rules and useless tasks, while the children are chastised and disciplined in a manner that is contrary to justice and charity. To the aged it is a house of slow death, to the young it is a house of torture. Paupers are the failures of society, and the doom of such is that they shall be taken to eke out the rest of their miserable existence within the walls of the Workhouse, to pick oakum.

The sexes are lodged in separate wards enclosed by high walls, and every door is locked, and barred, and guarded, to preserve that austere morality for which these institutions are famous. That the piteous condition of these unfortunates may not arouse any sympathy in the casual visitor, the outcasts are clad in fustian suits, or striped cotton dresses, in which uniform garb they become undistinguishable, and excite no interest. Their only fault was that they had become old, or so enfeebled by toil and sickness that they could no longer sustain themselves, and this is so heinous and grave in Christian England that it is punished by the loss of their liberty, and they are made slaves.

At one time in English history such wretches were left to die by the wayside; at another time, they incurred the suspicion of being witches, and were either drowned or burnt; but in the reign of Queen Victoria the dull-witted nation has conceived it to be more humane to confine them in a prison, separate husband from wife, parent from child, and mete out to each inmate a daily task, and keep old and young under the strictest surveillance. At six in the morning they are all roused from sleep; and at 8 o'clock at night they are penned up in their dormitories. Bread, gruel, rice, and potatoes compose principally their fare, after being nicely weighed and measured. On Saturdays each person must undergo a thorough scrubbing, and on Sundays they must submit to two sermons, which treat of things never practised, and patiently kneel during a prayer as long as a sermon, in the evening.

The scourge of the workhouse was a one-handed schoolmaster called James Francis whose cruelty seemed to know no bounds. Francis appeared to have been implicated in the death of a classmate of Stanley called Willie Roberts. On hearing of Willie's death, Stanley and several other boys sneaked into the workhouse mortuary and discovered his body covered in scores of weals. Stanley finally left the workhouse in 1856 after a violent showdown with Francis.

'Very well, then,' said he, 'the entire class will be flogged, and, if confession is not made, I will proceed with the second, and afterwards with the third. Unbutton.'

He commenced at the foot of the class, and there was the usual yelling, and writhing, and shedding of showers of tears. One or two of David's oaken fibre submitted to the lacerating strokes with a silent squirm or two, and now it was fast approaching my turn; but instead of the old timidity and other symptoms of terror, I felt myself hardening for resistance. He stood before me vindictively glaring, his spectacles intensifying the gleam of his eyes.

'How is this?' he cried savagely. 'Not ready yet? Strip, sir, this minute; I mean to stop this abominable and barefaced lying.'

' I did not lie, sir. I know nothing of it.'

'Silence, sir. Down with your clothes.'

'Never again,' I shouted, marvelling at my own audacity.

The words had scarcely escaped me ere I found myself swung upward into the air by the collar of my jacket, and flung into a nerveless heap on the bench. Then the passionate brute pummelled me in the stomach until I fell backward, gasping for breath. Again I was lifted, and dashed on the bench with a shock that almost broke my spine. What little sense was left in me after these repeated shocks made me aware that I was smitten on the checks, right and left, and that soon nothing would be left of me but a mass of shattered nerves and bruised muscles.

Recovering my breath, finally, from the pounding in the stomach, I aimed a vigorous kick at the cruel Master as he stooped to me, and, by chance, the booted foot smashed his glasses, and almost blinded him with their splinters. Starting backward with the excruciating pain, he contrived to stumble over a bench, and the back of his head struck the stone floor; but, as he was in the act of falling, I had bounded to my feat, and possessed myself of his blackthorn. Armed with this, I rushed at the prostrate form, and struck him at random over his body, until I was called to a sense of what I was doing by the stirless way he received the thrashing.

I was exceedingly puzzled what to do now. My rage had vanished, and, instead of triumph, there came a feeling that, perhaps, I ought to have endured, instead of resisting. Some one suggested that he had better be carried to his study, and we accordingly dragged him along the floor to the Master's private room, and I remember well how some of the infants in the fourth room commenced to howl with unreasoning terror.

Terrified of the consequences of his actions, Stanley absconded over the workhouse wall and subsequently ran away to sea.

HM Stanley, 1890

HM Stanley commemorative plaque

© Peter Higginbotham.

After 1930, the workhouse became St Asaph Public Assistance Institution. From 1910 until 1948, the St Asaph Infectious Diseases Hospital also operated on the site.

The HM Stanley Hospital closed in around 2010 and redevelopment of the site is anticipated.

Children's Home

In 1913, the union opened a children's home at The Roe, St Asaph. In 1924, the home could accommodate 30 children, with A.M. Palmer as the Superintendent.

Staff

Inmates

Records

Note: many repositories impose a closure period of up to 100 years for records identifying individuals. Before travelling a long distance, always check that the records you want to consult will be available.

- North East Wales Archives (Hawarden), The Old Rectory, Rectory lane, Hawarden, Flintshire, CH5 3NR. The extensive holdings include: Guardians' minute books (1841-1915, 1918-1930); Admissions and discharges (1842-1933); Births (1866-1947); Deaths (1866-1913); Creed register (1869-1928); etc.

Bibliography

- The Builder 6th June, 1903.

- Davies, Dawn et al (2012) A History of H.M. Stanley Hospital

- Parry-Jones, Edward (1981)From Workhouse to Hospital: The Story of HM Stanley Hospital, St Asaph 1840-1980 (Clwyd Health Authority)

- Stanley, Sir HM (ed. Stanley D) (1909) The Autobiography of Sir Henry Morton Stanley, G.C.B. (London: Sampson, Low, Marston & Co.Ltd)

- NEW! Workhouses of Wales and the Welsh Borders. The story of the workhouse across the whole of Wales and the border counties of Cheshire, Gloucestershire, Herefordshire and Shropshire. More...

Links

- A History of H.M. Stanley Hospital (Free download)

Acknowledgment

- Thanks to Huw Thomas for the plan of St Asaph.

Unless otherwise indicated, this page () is copyright Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.