Gateshead, Durham

Up to 1834

A parliamentary report of 1777 recorded township workhouses in operation at: Crawcrook (with accommodation for up to 20 inmates), Gateshead (50), Nether Heworth and High Heworth (15), Ryton Woodside (20), Stella (10), Whickham (60), and Winlaton (36).

In the seventeenth century, Gateshead built a poor house in St Mary's churchyard. Another poor house was acquired in 1750. It was located on the east side of the High Street in what had been built as an almshouse in 1731 through a 1728 bequest of Newcastle merchant, Thomas Powell. In 1750, the building was converted into a poor house and then later a workhouse. Under the terms of the bequest, this change was illegal but was not questioned for almost a century. It reverted to being an almshouse in 1841 after an inquiry. The workhouse's rules in 1813 required clean blankets every six months, clean sheets every three weeks and a daily wash for the inmates. Powell's Almshouses were finally demolished in 1947 and replacement homes were built in Cross Keys Lane in 1962.

After 1834

Gateshead Poor Law Union formally came into existence on 12th December, 1836. Its operation was overseen by an elected Board of Guardians, 30 in number, representing its 9 constituent townships as listed below (figures in brackets indicate numbers of Guardians if more than one):

County of Durham: Crawcrook, Gateshead (10), Heworth (6), Ryton, Ryton Woodside, Stella, Whickham (4), Winlaton (5).

The population falling within the Union at the 1831 census had been 31,017 with parishes ranging in size from Chopwell (population 254) to Gateshead itself (15,177). The average annual poor-rate expenditure for the period 1834-36 had been £9,011 or 5s.10d. per head of the population.

The first Gateshead Board of Guardians' meeting took place in the Justice Room of the Goat Inn, Bottle Bank, on 14th December, 1836. The new union inherited five existing workhouses from its member townships and it was initially decided to retain those at Gateshead and Heworth and sell off the others at Swalwell, Winlaton, and Ryton Woodside. However, at a Board meeting in January, 1838, it was decided that the old buildings were inadequate and that a new workhouse was required.

The Rector's Field / Union Row Workhouse

The site of the new building was at Rector's Field, off what became Union Row, and the new workhouse for 276 inmates was completed on 13th July 1841. The original intent was to include a hospital in the plans, but rising costs led to this being dropped. The final building had a simple T-shaped plan. Its location and layout are shown on the 1855 map below.

Gateshead Rector's Field workhouse site, 1855.

According to an 1890 directory, the workhouse occupied "a large range of stone buildings standing on rising ground called the Windmill Hills".

Nearby residents of the fashionable Claremount Place repeatedly complained against offensive smells emanating from the workhouse but an investigation in 1848 revealed that these were caused by sewage from Claremount place itself entering the workhouse grounds.

The workhouse was regularly overcrowded for which the solution was to sleep inmates two to a bed, and to slacken the strict separation of adults and children. Small additions were made to the buildings including a small sick ward in 1851, and a 'temporary' fever hospital in 1866 (still in use in 1887). In 1868, a special committee drew up extensive development plans which included new hospitals, school rooms, refractory wards, a dining hall, staff quarters, a permanent fever hospital, and a board room. However, obtaining the required land in the vicinity of the workhouse was by now impossible and the Poor Law Board recommended that a completely new workhouse be established at a new site. However, the cost-conscious Guardians refused to contemplate such a move and the overcrowding continued with the result that by 1874 children were sleeping three to a bed. In the same year, two instances were discovered of girls in the workhouse having been made pregnant by inmates. By 1879, the workhouse had 550 inmates in residence.

The next few years saw numerous unsuccessful attempts at obtaining a new site — those considered included ones at Deckham Hall, Carr Hill, Heworth, Low Fell, Saltwell, and Windy Hill Farm, Whickham. Eventually, the Board was offered High Teams Farm at Bensham which it accepted in 1885.

The Union Row site was sold off in the early 1890s and Woodbine Street erected on the site.

The High Teams Workhouse

In 1885, a competition was held for plans for the new workhouse and the joint winners were Messrs Newcombe and Knowles of Newcastle-upon-Tyne, and JH Morton of South Shields who also designed the workhouse at South Shields. The new workhouse was to accommodate 922 inmates, with a school for 300 children, at an estimated cost of £40,110. The architects provided a "bird's-eye view" of their proposed design.

Gateshead proposed workhouse design from the north-west, 1886.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Gateshead proposed workhouse plan, 1886.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Much of the preparatory work on the High Teams site, such as levelling and brick-making, was done by unemployed men under a 'labour test' scheme, where poor relief was given in return for the performing of manual labour. The new workhouse was occupied in June, 1890.

The new workhouse had four main areas. There was an entrance block with porter's lodge and casuals' and receiving wards on Workhouse Lane at the west. The main building at the centre of the site included administrative offices, kitchens, and male and female wards. A hospital was at the south-east of the site, having a central administration block flanked by pavilion wards for male and female patients. Finally, there was the school at the north of the site, also arranged with a central administrative block and separate pavilions for boys and girls. After the building of the union's cottage homes at Shotley Bridge in 1896-1901, the school block was presumably converted to other uses. The site layout in 1914 is shown below.

Gateshead workhouse site, 1914.

The site later became High Teams Institution. In 1938, the Institution's hospital facilities separated to become Bensham General Hospital. The remainder of the establishment was renamed Fountain View after 1948 and provided hostel accommodation for the homeless. Most of the workhouse buildings were demolished in 1969. All that now remains is the administrative block and the northern pavilions of the original hospital building.

High Teams Hospital Pavilions and Administrative block from the west, 2001.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The former workhouse site is now known as Bensham Hospital, providing care mainly for the elderly.

Shotley Bridge Cottage Homes

In 1896, the Gateshead Union began the construction of a cottage homes site at Corbridge Road, Medomsley, near Shotley Bridge. The homes were intended to remove pauper children, formerly residing at the workhouse, to accommodation that was free from the 'workhouse taint'. Over the following five years, six double cottages was erected to designs by W. Lister Newcombe of Newcastle-on-Tyne. The boys' cottages were given the names of trees (ash, oak, etc.) and the girls ' homes those of flowers (rose, lilac, etc.) Each home housed a "family" group of fifteen to twenty children looked after by a house mother. A total of 120 boys and 90 girls children could eventually be accommodated at the site which was also known as the Medomsley Cottage Homes.

A report of the scheme appeared in Building News in 1897:

THE site of these buildings is at Shotley Bridge, near Newcastle-upon-Tyne, and commands a fine view of the surrounding country. Gas and water-mains are in the road fronting the site. The waste-water drainage will be disposed of by irrigation upon the land. Earth-closets are used throughout. The walls are to be built of Tow Law stone—a very hard and close light-coloured local stone; external walls, 18in. thick, internal 9in., and lesser walls of brick. The roofs are covered with New York green Vermont slates. All joinery and fittings are of the best description in deal. The walls of cottages, administrative house, and porter's lodge are plastered internally. The hospital walls are plastered with Adamant, and the wards, lavatories, and bath-rooms of this building have glazed brick dadoes, all angles rounded, and special rounded. skirtings next floors. All the joinery in this building has been specially designed, free from all mouldings of a character to collect dust, and attention has been given to the internal finishings, and especially to the light and ventilation, while the arrangement of the hospital generally has been planned in accordance with the latest ideas. The drainage scheme has received special attention ; patent glazed channeling has been introduced to the manholes, in which the benching and piping are in one. The drainage is arranged so that at a future time the system may be connected with a sewer. The accommodation is for 120 boys and 90 girls in semidetached cottages, three cottages being for boys and three for girls. The cottages consist of living and dining-room, mother's room, kitchen, lavatory and bath-room on ground-floor, and upon the first floor two bedrooms, mother's bedroom, and linen-room. At the rear of the cottages are placed washhouse, w.c.'s, coal, wood, and earth-stores in a detached building. The workshops are for the technical training of the boys in various trades, and are planned and fitted for this purpose. With this group of buildings is placed the general stores for grocery, haberdashery, &c., and in front of this is the superintendent's quarters and office, committee-room, and. surgery. The porter's lodge consists of an office and living-room and bedroom over, and out-offices. The hospital is situated upon the highest part of the site, and is planned to be available either for general sick or isolation cases. The probation, or receiving, home for children is situate near the porter's lodge, and has every convenience. It is so placed that children, when admitted, are taken direct to the home without passing any other building, and it has a separate drive to the hospital for the same purpose. The contract drawings and general scheme have been somewhat modified in execution to meet the requirements of the Local Government Board. The number of cottages has been increased, and, exclusive of the receiving home, which has been removed to another site, will cost something like £21,000. Mr. Cecil A. Sharp, A.R.I.B.A., of Newcastle and London, is the architect of this work, which was obtained in competition.

The homes were opened in 1901.

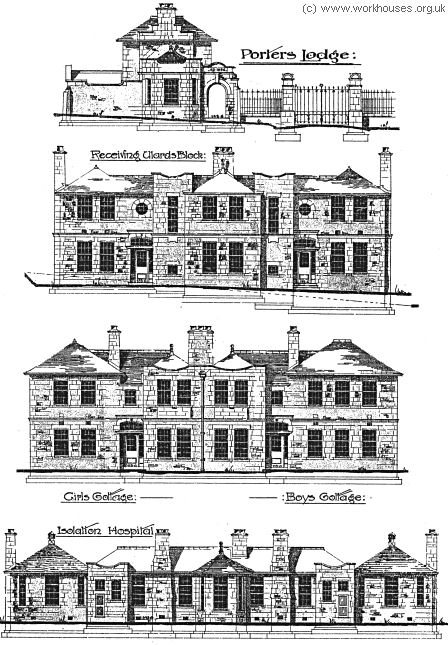

Gateshead cottage homes architect's designs, c.1897.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Gateshead cottage homes architect's designs, c.1897.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The site layout is shown on the 1923 map below.

Gateshead cottage homes site, 1923.

Gateshead cottage homes from the north, c.1905.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Gateshead cottage homes from the north-east, c.1905.

© Peter Higginbotham.

By 1914, the cottage homes children were attending the Benfieldside council schools.

The homes no longer exist and the Hassockfield Secure Training Centre now occupies the site.

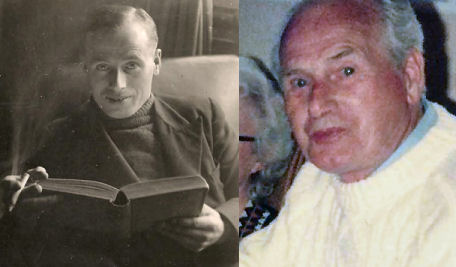

Charles Harrison was a resident of the cottage homes from approximately 1916 to 1924. His daughter Sonja has kindly contributed her father's memories of the home (below), which he recounted near the end of his life in 1997.

There were four of us: William, me, John and our sister, Harriet. Our mother died in just before Christmas 1916 and we didn't have a very good father. Often we were left on our own and sometimes in trouble. We were very hungry in those days. Our lives were sad, we had to go in queues, waiting for soup or what ever we could get.

My father married again but things did not go right with our stepmother and we children were sent to a children's home in Medomsley Edge, near Consett. The other village was Shotley Bridge. The home was good for us, we had to do what our foster mothers told us. The foster mother was very good to us. Her name was Mrs Jeffery. Everyone called her Mother. I cried when leaving her, she was good as a mother.

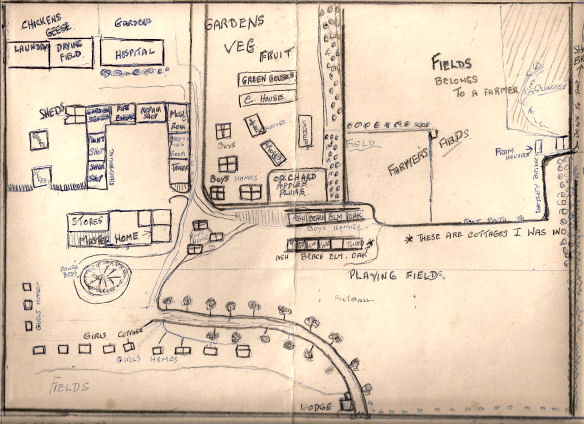

The cottages were built so that when the master and the mistress started inspection they first inspected the bedrooms. (The cottages were named Ash, Beech, Elm and Oak. I was in Oak.) They started by going upstairs in Ash Cottage, a master key through the cottages so on to Beech and so on, coming downstairs in Oak. Then back through the ground floor. That was done every week. Any complaints were written in the foster mother's book which she kept.

The other cottages were in twos and, of course, there were cottages for the girls. It was a massive place. But everything was very strict ruling. No-one said "I will not do it." You had to do what was required from the foster mother. For all the years I was there, I did learn a lot. My best was shoemaking. Starting from the uppers, cutting out the leather for the heels and soles, until I could do the shoes. These were for the children at the homes.

Of course, I learned the proper way in making beds, washing and scrubbing and polishing. Everything was very clean, even the long wooden tables had to be scrubbed. Everyone had a turn in all the rooms, even the outside toilets had to be cleaned.

Up early in the morning, wash and clean before breakfast and if you were 13½ years or more, you were taught a trade. Such as shoemaking, tailoring, gardening, painting and the girls made frocks , dresses and did knitting etc and cooking, but not in the boys' cottages. We were taught cooking too. But we were not always working, we could go out to play etc. In the dark evenings we read, did drawing or what ever games there were, we did not have many.

There were sometimes 12 or 14 in each cottage and on the dark evenings we were in bed by 8pm, but before that everyone had to clean their boots; give themselves a good wash and show the foster mother how clean you were before going to bed.

All the time I was there I got a good smacking if I was rude. Some of the mothers were shocking to the children. But we got by knowing that there was good food waiting for us. I remember being sent to bed for being cheeky or told to scrub the floor or do polishing. Or get sent to the master for the cane, or what ever came to hand...

It was home to me. I wondered how I would have been if my father and stepmother had kept us with them. But I thank God they sent to the children's home, although the strict ways were harsh, but it made us children wanted. You begin to have feelings for your foster mother, I am sure I did.

When the time came for me to leave and go somewhere else, they made arrangements for me to have some sort of job, I picked shoemaking which I liked. I left school at 13½ years and did my training in the shoe shop at the home. One day the master and the mistress, that's what we had to call them, said to come over to the big house. They said "You are fourteen years old now, and we shall soon send you to a training farm." A while later the home sent me to a place on a farm near Haverhill, I could not argue... but that is another story.

Charles Harrison c.1939 (left) and mid-1990s (right).

© Sonja Lightfoot.

Charles also sketched out a plan of the homes (below) as he remembered them — his memory proved remarkably accurate some seventy years later. (Click on the picture for a larger version.)

Charles Harrison's plan of Gateshead Cottage Homes.

The Whinney House Workhouse and Sanatorium

In the early 1900s, a scheme was proposed to set up a tuberculosis (TB) sanatorium jointly run by several unions in the north-east, including Gateshead. In 1906, after the scheme was abandoned, the Gateshead Guardians began to pursue their own plans. In 1909, after weathering opposition to their scheme from the Local Government Board, they acquired the Whinney (sometimes spelt Whinny) House estate at Shotley Bridge for the purpose of erecting a tuberculosis sanatorium.

The 56-bed sanatorium, designed by Newcastle architects Newcombe and Newcombe, cost around £4,500 and opened in 1912. The building was a simple two-storey structure on elevated ground at the east of the site, facing to the south-west.

In addition to the sanatorium, it was also decided to erect additional workhouse buildings on the site, designed by the same architects, and accommodating around 400 inmates. This facility was probably intended to relieve pressure on the High Teams workhouse by removing elderly and infirm inmates and allowing High Teams to develop its function as a hospital. On maps from this period the buildings are described as 'Home for the Aged and Infirm'.

Shotley Bridge site, 1923.

The workhouse/home buildings followed a typical pavilion-plan layout with a central administrative block, also containing a nurses' home, with large three-storey ward blocks to each side, connected to the centre by a single-storey enclosed corridor. A laundry and boiler-house were located to the north of the complex.

Shotley Bridge workhouse/home building from the south-east, 2005.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Shotley Bridge administration block / nurses' home from the north-west, 2005.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Shotley Bridge administration block / nurses' home, 2005.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Shotley Bridge connecting corridor, 2005.

© Peter Higginbotham.

From 1919, the site was leased to the Ministry of Health to house military casualties, and in around 1922 was taken over by the Ministry of Pensions for ex-servicemen who still required medical treatment.

In 1926, the site became a Mental Deficiency Hospital for the city of Newcastle-on-Tyne. The site layout is shown on the 1939 map below.

Shotley Bridge hospital site, 1939.

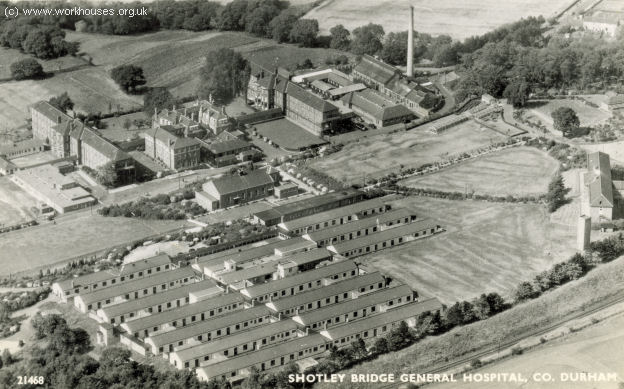

In 1941, the institution became the Shotley Bridge Emergency Hospital and sixteen hut blocks were erected on the eastern part of the site. In 1948, the hospital joined the National Health Service as Shotley Bridge General Hospital.

Shotley Bridge aerial view from the south-east.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Major new buildings have now been erected at the south of the site. The workhouse buildings are now (2005) no longer in use and are awaiting redevelopment. The sanatorium and hut blocks have been demolished.

Staff

Inmates

Records

Note: many repositories impose a closure period of up to 100 years for records identifying individuals. Before travelling a long distance, always check that the records you want to consult will be available.

- Tyne and Wear Archives, Discovery Museum, Blandford Square, Newcastle upon Tyne NE1 4JA. Few local records survive. Holdings include Guardians' minutes (1836-1930); Register of children in homes (1908-49).

Bibliography

- Manders, FWD (1973) A History of Gateshead (Gateshead: Gateshead Corporation).

Links

- None.

Acknowledgment

- Thanks to Sonja Lightfoot for kindly providing the reminiscences and pictures of her father.

Unless otherwise indicated, this page () is copyright Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.