Changing Times?

Despite the picture that is often painted, life in the workhouse was not entirely bad and slowly got more tolerable as time went on. Some of the changes were brought about by the efforts of organisation such as the Workhouse Visiting Society and the election of female and working-class members to the Boards of Guardians which ran each union.

Relaxations very gradually began to creep in from the 1880s including the allowance of books, newspapers and snuff for the elderly, toys for the children, and tea-brewing facilities for deserving inmates. Living conditions were often healthier than existed in much poor housing of the time. Although monotonous, the food was regular and reasonably wholesome and improved considerably after the dietary reforms in 1900. The staff in many institutions were kindly, and the brutal treatment that was sensationalized in the press was probably much the exception. The treatment of elderly inmates in particular had become much more relaxed. From the 1890s, elderly inmates at the Macclesfield workhouse could wear their own clothes, leave the workhouse for daily afternoon walks, have friends to visit in the afternoon, and even keep their own pets. In Abingdon, in the late 1920s, the inmates had a wireless in their day room, and supervised weekly excursions to the local cinema.

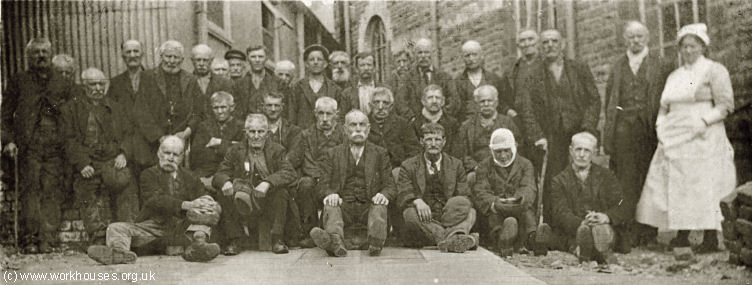

Swansea workhouse inmates, date unknown.

© Peter Higginbotham.

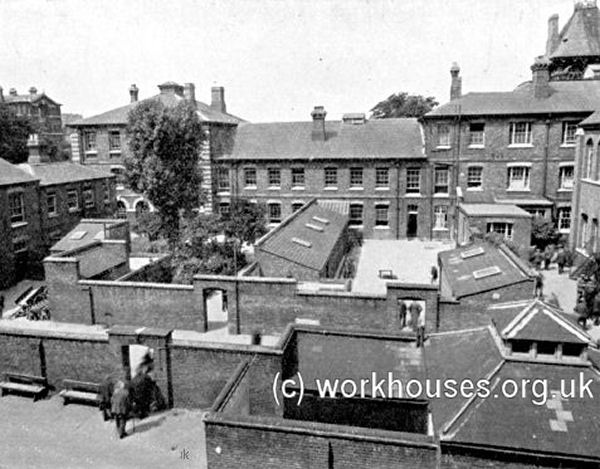

St Marylebone men's yard, c.1901.

© Peter Higginbotham.

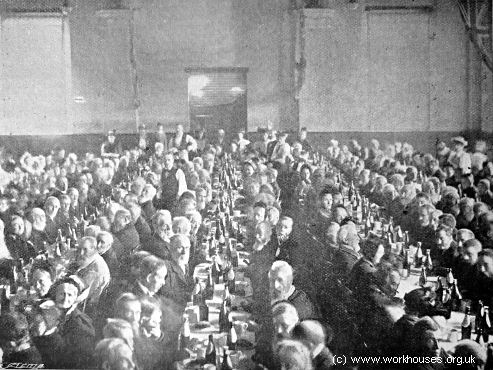

At many workhouses, children and aged inmates had occasional outings to the country or the sea, although these were not always the sedate affairs that might be expected. From 1891, inmates from Camberwell's Gordon Road and Constance Road workhouses had an annual summer excursion to the seaside. For their 1896 day out to Bognor Regis, a special 650-seat train was chartered and at around 9a.m. the party set off. The group consisted mostly of elderly inmates aged 60 to 90, together with a number of young children from the workhouse. Dinner and tea were provided at the Bognor Town Hall after which the men were given tobacco, and the women and children sweets. However, many of the group had apparently obtained money from their friends and after being liberated from the workhouse had headed straight for the nearest public house before boarding the train. On arrival at Bognor, they had continued drinking and had then gone for their dinner at which beer was also served. After dinner, there were more visits to the local public houses. It was later reported that a number of cases had occurred of disorderly conduct and indecent behaviour on secluded parts of the beach. A photograph of the inmates at their official dinner shows that beer was indeed served.

Camberwell workhouse inmates' outing to Bognor Regis, 1896.

© Peter Higginbotham

After 1930, when Boards of Guardians were officially abolished, many former workhouses became "Public Assistance Institutions" — continued to provide care for the elderly and infirm and the destitute. Such establishments were often given idyllic-sounding names such as "The Laurels" but continued to be referred to by local people as "the workhouse" for several decades and still carried the same stigma. The fact that PAIs invariably inherited their premises, staff and inmates from the workhouse era meant that real change was slow to come. For many years, the "superintendent" of the Institution would still be referred to as "Master" by the former "inmates", now called "residents". Internal changes often meant little more than the supposed abolition of uniforms (now replaced by "suitable clothing") and a little more freedom to come and go.

One highly visible change that did often take place was the removal of the walls that had divided the external yards for the different classes of workhouse inmate. The two views below of the Woolwich workhouse show the same area before and after the removal of these walls.

Woolwich rear of main block from the east, late 1920s.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Woolwich rear of main block from the east, 1930s.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The few changes that did take place were often as a result of pressures from outside such as the campaign led by Olive Matthews to give elderly PAI inmates a weekly pocket money allowance. As a result, the 1938 Poor law Amendment Act enabled local authorities to give each inmate up to two shillings a week to spend as they wished. However, the fact that this was an option rather than an obligation meant that not all local authorities made this payment.

In some respects, the elderly poor were actually worse off in the years after 1930. Many former workhouse infirmaries were "appropriated" by local authority public health committees. Although facilities in these hospitals often benefited from their new role as public health hospitals, the change in status meant that the sick poor no longer had a right of entry as had previously been the case. The resulting shortage of beds for the elderly sick meant that many had to be be admitted to the remaining and increasinly overcrowded PAI infirmaries, or even occupy non-hospital beds and so lose their pension rights.

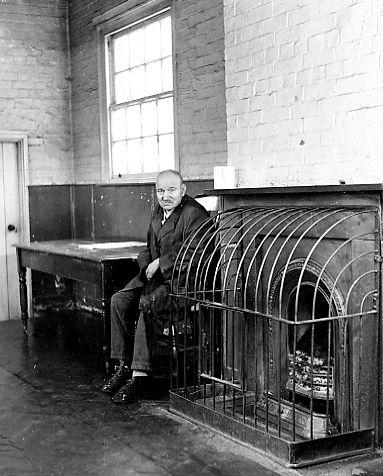

"Man by Fire" - Wantage, 1946

© Oxfordshire Photographic Archive.

Unless otherwise indicated, this page () is copyright Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.