The New Poor Law

Introduction

In 1832, a Royal Commission, under the chairmanship of the Bishop of London, was appointed to review the administration of the Old Poor Law - the body of legislation governing the relief of the poor founded on the 1601 Poor Relief Act and subsequent legislation. The Commission accumulated a mass of information, the bulk of which came in the form of reports from a team of Assistant Commissioners who visited parishes across the country, and via questionnaires which were returned from around 1500 parishes - around ten per cent of the total.

The Commission's report, presented in March 1834, was largely the work of two of the Commissioners, Nassau Senior and Edwin Chadwick. The report took the view that poverty was essentially caused the indigence of individuals rather than economic and social conditions. Thus, the pauper claimed relief regardless of his merits: large families got most, which encouraged improvident marriages; women claimed relief for bastards, which encouraged immorality; labourers had no incentive to work; employers kept wages artificially low as workers subsidized from the poor rate.

The report made a series of 22 recommendations which were to form the basis of the new legislation that followed in the same year. Its main legislative proposal was that:

In addition, it recommended:

- The grouping of parishes for the purposes of operating a workhouse

- That workhouse conditions should be 'less eligible' (less desirable) than those of an independent labourer of the lowest class

- The appointment of a central body to administer the new system

The report also revived the workhouse test — the belief that the deserving and the undeserving poor could be distinguished by a simple test: anyone prepared to accept relief in the repellent workhouse must be lacking the moral determination to survive outside it.

The 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act

In the wake of the Royal Commission's report came the Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834 — An Act for the Amendment and better Administration of the Laws relating to the Poor in England and Wales (4 & 5 Will IV c. 76) which received Royal Assent on August 14th, 1834.

You can read the full text of the 1834 Act

Title page of the 1834 Poor Law Act

© Peter Higginbotham.

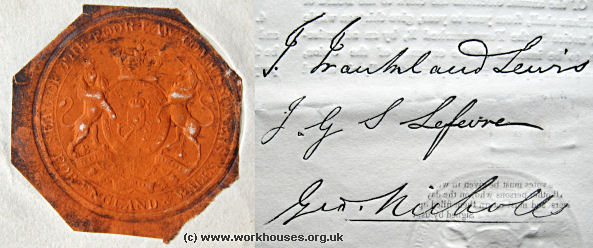

The 1834 Act was largely concerned with setting up the legal and administrative framework for the new poor relief system. At its heart was the new Poor Law Commission which was given responsibility for the detailed policy and administration of the new regime. Three Poor Law Commissioners were appointed (George Nicholls, John Shaw-Lefevre and Thomas Frankland Lewis) with Edwin Chadwick as their Secretary. The Commission was based at Somerset House in London.

The seal and signatures of the Poor Law Commissioners.

© Peter Higginbotham.

One of the Commission's first tasks was to set about dividing the 15,000 or so parishes of England and Wales into new administrative units called Poor Law Unions each run by a locally elected Board of Guardians. (Local Act Incorporations and Gilbert Unions were exempted from the new scheme, something that was to irritate the Commission and its successors for many years.) The funding of each Union and its workhouse continued to come from the local poor rate with each parish contributing in proportion to its poor relief expenditure over the previous three years. Following the principle established by the 1818 Sturges Bourne Act, ratepayers were given votes (up to six) in proportion to the value of their property.

The creation on the new unions was undertaken by a team of Assistant Commissioners visiting each area and conducting meetings with local parish officials and landowners. In some areas, landowners with large estates were able to achieve considerable influence over the groupings of parishes forming each union. Landowners generally preferred to keep their estates within a single union which would allow them the maximum of influence on its Board of Guardians. The new Potterspury union in Northamptonshire, for example, ended up with only eleven member parishes, eight of which were owned entirely or in part by the Duke of Grafton.

The overall working and implementation of the new system was put into practice by means of a large volume of orders and regulations issued by the Commission which specified every aspect of the operation of a Union and its workhouse. The Commission had the power to issue 'General Orders' which would apply to a number of unions, and 'Special Orders' which were specific to one. General Orders required parliamentary approval, while Special Orders did not. The Commission got around this restriction by repeatedly issuing identical 'special' orders to multiple individual unions. It was not until 1841 that the first General Orders were submitted for parliamentary approval. Many of the previous special orders were subsequently revised and reissued an general orders culminating in the issue in 1847 of the Consolidated General Order which became the 'bible' of the system's operation.

The 'Bastardy Clause'

One of the most controversial parts of the Act was the 'Bastardy Clause' (actually a sequence of several clauses) which made the obtaining of affiliation orders much more difficult and expensive than had formerly been the case. Previously, such orders were obtained through local Petty Sessions courts but after 1834 had to be heard at county Quarter Sessions and could only be initiated by Overseers or Guardians. Evidence of paternity claims now also had to be "corroborated in some material particular", something that was often impossible to achieve. The Act effectively made illegitimate children the sole responsibility of their mothers until they were 16 years old. If mothers of such children were unable to support themselves and their offspring, they would have to enter the workhouse. The 1834 Act, it was hoped, would make the consequences sufficiently unattractive to deter women from risking extra-marital pregnancy. Perhaps unsurprisingly, it was a highly unpopular and contentious measure and was diluted in 1839 by an Act (2&3 Vic. c.85.) which allowed affiliation claims to again be heard by local magistrates at Petty Sessions. The clause was effectively overturned by a further Act in 1844 (7&8 Vic. c.101) which enabled an unmarried mother to apply for an affiliation order against the father for maintenance of the mother and child, regardless of whether she was in receipt of poor relief.

Settlement

The 1832 Royal Commission had proposed a simplification of the settlement laws so that birth in a parish would become the only means of acquiring settlement. However, this suggestion was not taken up, although the 1834 Act removed a year's hiring and service in a parish office as options to gain settlement. A provision to allow a union, rather than its individual parishes, become the area of settlement was only taken up by one parish, Docking in Norfolk.

Following the 1834 Act, a illegitimate child now took its mother's settlement until it reached the age of sixteen or acquired settlement in its own right. The previous system, where such a child gained settlement from its place of birth, had sometimes led parishes to try and remove from within their borders heavily pregnant single women so that their children would not be a burden on the ratepayers.

In 1846, the already complex settlement laws were further complicated by an Act which introduced the new concept of 'irremovability'. Amongst other things this gave protection against removal to anyone who had been resident in a parish for five years. This privilege was not, however, available to those living outside their home parish and who were in receipt of non-resident poor relief from that parish. In order to prevent a flood of new relief claims from those poor who discovered that they were now irremovable, 'Bodkin's Act' was passed shortly afterwards to place the cost of such claims on the union's common fund rather than on individual parishes. From 1865, one year's continuous residence in a union would qualify a person as being irremovable.

Despite these changes, issues of settlement and removal continued to occupy a significant amount of unions' time and money. In 1907, more than 12,000 individuals were removed from one union to another in England and Wales, the larger number of these being from London and other large cities.

Opposition to the New Act

The 1834 Act received much criticism, including from The Times which on 30th April 1834 (prior to its enactment) claimed that bill would "disgrace the statute-book."

Within weeks of its opening, the first new workhouse built under the new law at Abingdon was in the news when its master had been the subject of a murder attempt.

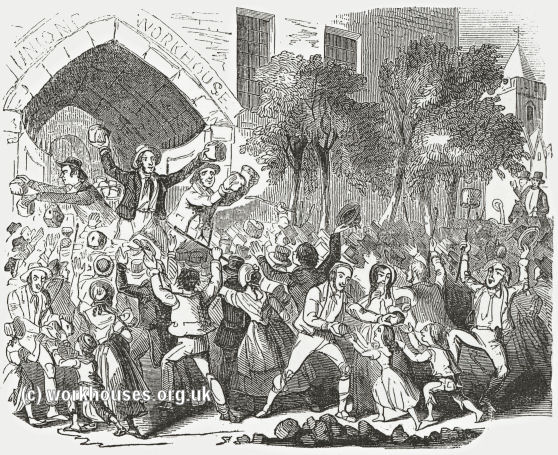

In the north of England, partly fuelled by economic depression, an Anti Poor Law movement took hold. In places such as Huddersfield, led by Richard Oastler, its supporters even included members of the Board of Guardians who obstructed the operation of the new Act by refusing to elect a Union Clerk, without whom no business could take place. In August 1842, the Stockport union workhouse was the subject of an attack by a mob of unemployed workers.

Stockport workhouse under attack, 1842.

© Peter Higginbotham.

In Wales, particularly in the central and north-western regions, resistance to the building of workhouses was strong. By 1847, seventeen out of 47 unions had still not opened workhouses. One union, Rhayader, held out against erecting one until 1877. Attacks also took place on the workhouses at Llanfyllin where the Montgomeryshire Yeomanry prevented a mob from destroying the building, and at Narberth where special constables were employed to protect the site after a mob attempted to burn down the new workhouse.

However, at the heart of opposition to the new law was the hardship and brutality it engendered. In 1841, GR Wythen Baxter published his famous The Book of the Bastiles — a somewhat lurid compilation of newspaper reports, court proceedings, correspondence and so on, which graphically illustrated some of the horror stories relating to the New Poor Law. For example:

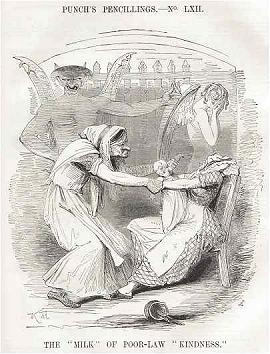

Two years later, in 1843 the satirical magazine Punch reported how in Bethnal Green "An infant, only five weeks old, had been separated from the mother, being occasionally brought to her for the breast."

In the Huddersfield Union, where five small old workhouses were still in use, there was public outcry in 1848 at conditions in the Huddersfield township workhouse. Conditions in the workhouse were appallingly cramped and unhygienic, with up to 10 children sharing a bed. The inmates' diet was miserable, even by workhouse standards. Conditions in the infirmary were even worse — a living patient occupied the same bed with a corpse for a considerable period after death, and the sick were left unwashed for days on end, in some cases besmeared in their own excrement.

The most notorious scandal was that at Andover Workhouse in 1845 where, it emerged, conditions were so harsh that inmates had resorted to scavenging for decaying meat from the bones that they had been set to crush. This case received enormous publicity and the fall-out from this was considerable.

Outdoor Relief

The Poor Law Commission devoted much energy to the abolition of outdoor relief to the able-bodied, which was a lynch-pin of the 1834 Act. This had proved particularly difficult in the industrial north. Outdoor relief was the subject of two important General Orders issued by the Commission:

- The Outdoor Labour Test Order of April, 1842, allowed relief (at least half of which was to be in food, clothing etc.) to be given to able-bodied male paupers who satisfied a Labour Test i.e. physical work, usually stone-breaking or oakum picking.

- The Outdoor Relief Prohibitory Order issued in December, 1844, prohibited all outdoor relief to able-bodied men and women apart from in exceptional circumstances.

The Labour Test Order was alone in force in 32 unions, mostly in the industrial north. The Prohibitory Order was alone in force in 396 unions. In 81 unions, both Orders were in force, allowing the Guardians some discretion in how to administer out-relief.

The Poor Law Board

In 1847, following the Andover scandal and other bad publicity, reports of internal quarrels and divisions, together with a desire by the government to make the poor law administration more directly accountable to parliament, the Poor Law Commission was abolished and replaced by a new Poor Law Board, with George Nicholls as its permanent secretary for the first three years of its life.

In 1852, the Poor Law Board attempted to standardise the regulations relating to the provision of out-relief. In August, it issued an Outdoor Relief Regulation Order which, unlike previous orders on the subject, included restrictions relating to the sick, aged and widows. Following numerous protests from Boards of Guardians who felt their discretionary powers were being interfered with, a revised Order was issued in December. This reverted to dealing with able-bodied males, but extended the conditions under which out-relief could be given in such cases.

In 1865, the Union Chargeability Act shifted the cost of poor relief from the parish to the union — each parish now contributed to a union fund based on its rateable value not on the number of paupers it had. The union, rather than the parish, became the area of settlement and the period of residency required for irremovability was reduced to one year.

The Metropolitan Asylums Board

In the 1860s, increasing concern about the state of London's workhouses, and in particular their medical facilities, led to pressure for changes in their management. In 1865, things came to a head when the medical journal The Lancet published revealed the appalling conditions in many workhouse infirmaries. Two years later, in 1867, the Metropolitan Poor Act was passed and the care on London's sick poor was brought under the care of a new body, the Metropolitan Asylums Board. Some reorganisation of London's unions was carried out, and all unions were now required to provide hospital accommodation on sites separate from the workhouse. The MAB erected a number of its own institutions for the care the city's fever, smallpox, and tuberculosis patients, and for what were then termed "imbeciles". The MAB's institutions were effectively England's first state hospitals.

The Local Government Board

In 1871, the Poor Law Board was replaced by the Local Government Board which included a much broader range of responsibilities such as sanitation and public health.

In the 1870s, the Local Government Board mounted a campaign to reduce the levels of out-relief expenditure. It also increased the pressure on the few remaining unions such as Todmorden, Rhayader and Presteigne who had held out against the building workhouses. It was assisted in this by The Divided Parishes and Poor Law Amendment Act, 1876 (39&40 Victoria c.61). The primary aim of this Act was to enable the Board to tidy up the boundaries of unions, particularly those that had parishes detached from the main area of the union or that crossed county borders. However, the Act also empowered the Board to dissolve any union "when it is expedient to do so for the purpose of rectifying or simplifying the areas of management, or otherwise for the better administration of relief...". Under the threat of dissolution, Todmorden and Rhayader finally agreed to build workhouses, with Rhayader taking in its first inmates in August 1879, making it the last union in the whole of England and Wales to do so.. Presteigne, however, was dissolved in 1877 and its constituent parishes distributed to adjacent unions.

The Local Government Board Offices, Whitehall.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Ireland

On 31 July 1838, following a report by George Nicholls, an Act for the more effectual Relief of the Destitute Poor in Ireland was passed. It was based for the most part on the same model that existed for England and Wales with relief centred on the workhouse. Initially, 130 Irish unions were created, with an additional 33 being added in 1848-50. For more information see the separate page on Ireland.

Scotland

In January 1843, a Commission of Enquiry was appointed to consider the operation of poor laws in Scotland. Their report, delivered on 2nd May 1844, noted that poor relief in Scotland was generally confined to the old, infirm, disabled, mentally ill and so on. Relief to the able-bodied was rare. They therefore proposed to broadly keep relief organized at the parish level although parishes, particularly in urban areas, should be united for settlement and poor-relief purposes, including the establishment of united poorhouses. They also proposed the creation of a Board of Supervision to oversee the management of each parish's poor relief. These proposals were put into effect on 4th August 1845 in an Act for The Amendment and better Administration of the Laws Relating to the relief of the Poor in Scotland (8 & 9 Vic. c. 83). For more information see the separate page on Scotland. You can also read the full text of the 1845 Act.

Poor Relief Disfranchisement

Prior to 1918, acceptance of poor relief disqualified the recipient from voting. However, from the 1870s there was an increasing use of workhouse medical facilities by those for whom admission to the main institution was not appropriate. In 1885, the Medical Relief Disqualification Removal Act (48&49 Vic. c.46) meant that anyone who was in receipt only of poor-rate-funded medical care no longer lost their vote.

The 1905 Royal Commission

By the start of the twentieth century, change was in the air. Two factors contributed to this. The first was the election of a significant number of women as Guardians - since the 1860s women had been active in improving workhouse conditions, particularly through bodies such as the Workhouse Visiting Society. The second, in 1892, was the lowering to £5 of the property rental value qualifying for Guardian election which enabled the election of working-class people as Board members.

In December 1905, a Royal Commission on the Poor Law and the Unemployed was appointed:

"To inquire: (1) Into the working of the laws relating to the relief of poor persons in the United Kingdom; (2) Into the various means which have been adopted outside of the Poor Laws for meeting distress arising from want of employment, particularly during periods of severe industrial depression; and to consider and report whether any, and if so what, modification of the Poor Laws or changes in their administration or fresh legislation for dealing with distress are advisable."

Over the next four years it carried out the most extensive investigation since the Royal Commission of 1832. Its 18 members included: C.S. Loch (Secretary of the London Charity Organization Society), William Smart (Professor of Political Economy at Glasgow University), Octavia Hill (campaigner for housing reform and co-founder of the National Trust), socialist reformers George Lansbury and Beatrice Webb (wife of Sidney Webb), former Guardians, Poor Law officials and clergymen.

The Commission was famously split and its recommendations were published as:

- A Majority Report, endorsed by fourteen of its members, which recommended the creation of a new Poor Law authority in each county or county borough, together with the replacement of workhouses by more specialized institutions catering for separate categories of inmate such as children, the old, the unemployed, and the mentally ill.

- A Minority Report, signed by four members (Beatrice Webb, George Lansbury, Mr F Chandler, and The Revd Russell Wakefield) was more radical and advocated the complete break-up of the Poor Laws and the transfer of its functions to other authorities to provide care for various groups. Its emphasis was on the prevention of destitution rather than its relief.

The Report was also published in a modestly priced Fabian edition and had a spectacular sale. A great propaganda campaign was organized by Sidney and Beatrice Webb in support of its recommendations for the prevention of destitution by the break-up of the Poor Law.

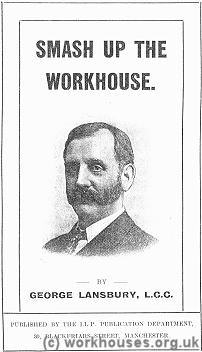

In 1911, George Lansbury, who in 1892 had become one of the first working-class Guardians in Poplar, wrote a pamphlet provocatively entitled Smash up the Workhouse. This argued that few, particularly able-bodied, people should need to be in workhouses. For those who had no alternative, there should be a softening of the workhouse regime.

In 1911, George Lansbury, who in 1892 had become one of the first working-class Guardians in Poplar, wrote a pamphlet provocatively entitled Smash up the Workhouse. This argued that few, particularly able-bodied, people should need to be in workhouses. For those who had no alternative, there should be a softening of the workhouse regime.

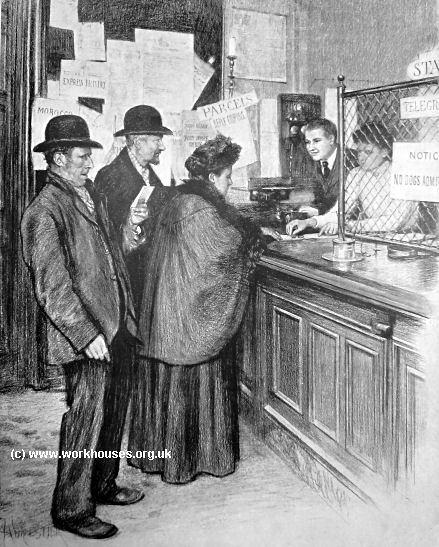

Although no new legislation directly resulted from the Commission's work, a number of significant pieces of social legislation took place in its wake. Jan 1st 1909 saw the introduction of the old age pension for those over 70 (up to 5s. a week for a single person, 7s.6d. for a married couple) although until 1911, anyone who had received poor relief in the previous twelve months was denied a pension. In 1911 unemployment insurance and health insurance began in a limited form.

Some of the first receipients of the old age pension, 1909.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The End of the Workhouse

From 1913 onwards, the term "workhouse" was replaced by "poor law institution" in official documents but the institution itself was to live on for a good many years yet.

During the First World War, many Boards of Guardians offered workhouse premises for military use, mostly as hospitals (for example at Bristol and Birmingham) but also for accommodating military personnel, prisoners of war (for example Banbury) and "aliens" (for example Islington).

The general depression in the years following the First World War, culminating in the miners' strike of 1926, put a tremendous strain on the system with some unions effectively becoming bankrupt. In some areas, where colliery owners also had influence with local Boards of Guardians, there were allegations that relief was deliberately reduced to break the strike. Conversely, where miners and union officials dominated a Board, there were complaints that the rates were being used to supplement strike funds.

Neville Chamberlain, Health Minister in the 1925 Conservative government, believed that that the poor-law system needed reforming and in 1926 pushed through a Board of Guardians (Default) Act which enabled the dismissal of a Board of Guardians and its replacement with government officials. This was followed by a further Poor Law Act in 1927, and in 1928 he introduced The Local Government Act which would in many respects bring about many of the measures proposed by the Royal Commission's Report in 1909. Essentially, this would abolish the Boards of Guardians and transfer all their powers and responsibilities to local councils. These were required to submit administrative schemes to end "poor relief" as such — "as soon as circumstances permit" — and provide more specific "public assistance" on the basis of other legislation such as the Public Health Act, the Education Act, and so on. The Act was passed on 27th March 1929 and came into effect on 1st April 1930 — a day which supposedly marked the end of the road for 643 Boards of Guardians in England and Wales.

Although some workhouse sites were closed, many institutions carried on into the 1930s virtually unaltered. Objections from Boards of Guardians and councils meant that changes were very slow in taking place. Ultimately, the 1929 Act did not succeed in abolishing the Poor Law — it merely reformed how it was administered and changed a few names. Poor Law Institutions became Public Assistance Institutions and were controlled by a committee of "guardians". However, physical conditions improved a little for the inmates, the majority of whom continued to be the old, the mentally deficient, unmarried mothers, and vagrants. Despite the official change in name, the Institutions often continued to be be referred to as workhouses.

The National Health Service Act of 1946 came into force on 5th July 1948. Even the sweeping changes that came with this had less impact than might be imagined. Institutions now came under the control of Hospital Management Committees under Regional hospital Boards but many still carried the stigma from their workhouse days. Many of these new "hospitals" also maintained "Reception Centres for Wayfarers", i.e. casual wards for vagrants, until the 1960s.

Bibliography

- Slack, Paul. The English Poor Law, 1531-1782, 1990, CUP.

- Webb, Sidney and Beatrice English Poor Law History, 1927, Longmans, Green & Co., London.

- Webb, Sidney and Beatrice English Poor Law Policy, 1910, Longmans, Green & Co., London.

Links

Unless otherwise indicated, this page () is copyright Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.