Andover, Hampshire

Up to 1834

Andover had a parish workhouse from around 1733. A parliamentary report of 1777 recorded that Andover's workhouse could house up to 120 inmates.

After 1834

Andover Poor Law Union was formed on 9th July 1835. Its operation was overseen by an elected Board of Guardians, 36 in number, representing its 32 constituent parishes as listed below (figures in brackets indicate numbers of Guardians if more than one):

County of Hampshire:

Abbots Ann, Amport, Andover (5), Appleshaw, Barton Stacey, Bullington, Chilbolton, Goodworth Clatford, Faccombe, Foxcott, Fyfield, Grateley, Hurstbourne Tarrant, Kimpton, Knights Enham, Linkenholt, Longparish, Monxton, Penton Grafton, Penton Mewsey, Quarley, Shipton Bellinger, South Tedworth, Tangley, Thruxton, Up-Clatford [Upper Clatford], Vernham [Vernhams] Dean, Wherwell.

County of Wiltshire: Chute, Chute Forest, Ludgershall, North Tidworth.

The population falling within the Union at the 1831 census had been 16,481 — ranging from Foxcott (population 95) to Andover itself (4,748). The average annual poor-rate expenditure for the period 1832-35 had been £12,715 or 15s.5d. per head of the population.

Andover workhouse was erected in 1836 at the west side of Junction Road in Andover. It was design by Sampson Kempthorne who was the architect of many other early Union workhouses including those for the Basingstoke, Droxford, Lymington and New Forest unions. Andover was based on his standard cruciform design with an entrance and administrative block at the east containing the board-room, porter's quarters, a nursery and stores. To the rear, four wings radiated from a central supervisory hub which contained the kitchens, with the master's quarters above. Females were accommodated at the north side and males at the south. The west of these wings contained the dining-hall which was also used as a chapel. Girls and boys school-rooms and dormitories lay down the west side with exercise yards beyond. Along the north side of the workhouse were casual wards and female sick wards. Male sick wards were at the south. The layout of the workhouse in shown on the 1873 map below.

Andover workhouse site, 1873.

Andover from the east, c.1907.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Andover from the east, 2000.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Andover from the east, 2000.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Andover rear of entrance block, 2000.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The main accommodation blocks radiated as wings from a central octagonal hub.

Andover from the south, 2000.

© Peter Higginbotham.

In 1922, it was reported that a 'plague' of 108 bats had been found under the roof of the master's quarters, an killed.

The workhouse building was later used as an annexe for Cricklade College but has now been converted to residential accommodation.

The Andover Workhouse Scandal

Andover had a reputation for being an extremely strict workhouse, largely due its fearsome Master Colin McDougal, a former sergeant-major who had fought at Waterloo in 1815. His wife, Mary Ann, was a force to be reckoned with and was once described by the Chairman of the Guardians as "a violent lady". The McDougals ran the workhouse like a penal colony, keeping expenditure and food rations to a minimum, much to the approval of the majority of the Guardians. Inmates in the workhouse had to eat their food with their fingers, and were denied the extra food and drink provided elsewhere at Christmas or for Queen Victoria's coronation. Any man who tried to exchange a word with his wife at mealtimes was given a spell in the refractory cell.

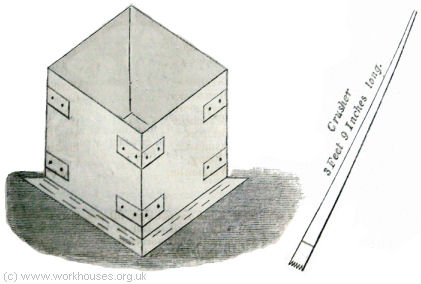

Work, too, was hard for the inmates. The workhouse's favoured occupation for able-bodied men was the strenuous task of crushing old bones to turn them into fertilizer. In 1845, rumours began to spread in the neighbourhood that men in the workhouse bone-yard were so hungry that they had resorted eating the tiny scraps of marrow and gristle attached to the old bones they were supposed to be crushing. Fighting had almost broken out when a particularly succulent bone came their way.

One of the Guardians, Hugh Mundy, was so concerned by these stories that he raised the issue at a board meeting but found little support from his fellow Guardians, apart from a decision to suspend bone-crushing during hot weather. He therefore took the matter to his local MP, Thomas Wakeley, who on Friday 1st August, 1845, asked a question in Parliament concerning the paupers of Andover who "were in the habit of quarreling with each other about the bones, of extracting the marrow... and of gnawing the meat." The Home Secretary expressed disbelief that such things were happening but promised to instigate an inquiry. The next day, Henry Parker, the Assistant Poor Law Commissioner responsible for the Andover union was despatched there forthwith to establish the facts of the matter.

Parker soon established that the allegations were largely true. In addition, he had discovered that the inmates had apparently regularly been given less than their due ration of bread. Parker, under pressure from his superiors to complete the investigation as soon as possible, had a difficult task, made harder by the close attention the case was receiving from the press. There was significant development on September 29th when McDougal resigned as Master. Trying to be helpful, Parker, recommended as a replacement an acquaintance of his own, the unemployed former Master of the Oxford workhouse. Unfortunately, it transpired that the man had been dismissed for misconduct. In October, the beleaguered Parker was asked to resign by the Poor Law Commissioners who, under attack from Parliament, the press, and the public, needed a scapegoat for the affair.

This was not the end of the matter, however. Parker published a long pamphlet defending himself, and his cause was quickly taken up by a group of anti-Poor Law MPs. Support, too, came from William Day, another recently dismissed Assistant Commissioner who had been given the difficult task of introducing the workhouse system in South Wales, where opposition to the New Poor Law was particularly strong. A further ally came in the form of Edwin Chadwick, Secretary to the Poor Law Commissioners, who had always been resentful at not being made a Commissioner himself.

On 8th November, 1845, the Commissioners implicitly acknowledged the validity of the outcry against bone-crushing by forbidding its further use. The disquiet rumbled on until, on 5th March, 1846, a Parliamentary Select Committee was set up to "enquire into the administration of the Andover union... and the management of the union workhouse... the conduct of the Poor Law Commissioners and... all the circumstances under which the Poor Law Commissioners called upon Mr Parker to resign his Assistant Commissionership."

A fortnight later, a fifteen-strong "Andover Committee" began work. It emerged that, due to some administrative error, inmates had been given short or inferior rations, even though the union had in 1836 adopted the least generous of all the Commissioners' suggested dietaries. A succession of witnesses revealed the grim and gory details of bone-crushing — it was heavy work with a 28-pound solid iron "rammer" being used to pummel the bones in a bone-tub. Apart from the appalling smell, it was back-breaking and hand-blistering work, yet even boys of eight or ten were set to it, working in pairs to lift the rammer. Men also suffered scarred faces from the flying shards of bone. Bone crushing could, however, make a good profit for the workhouse with old bones being bought in at 20 shillings a ton and the ground bone dust fetching up to 23 or 24 shillings a ton. It was embarrassingly revealed during the inquiry that the some of Andover Guardians had themselves bought the ground bones at a bargain price of 17 to 19 shillings a ton.

Bone-crushing equipment, 1840s.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The witnesses at the inquiry included former workhouse inmates such as 61-year Samuel Green:

Colin McDougal was also revealed to have been regularly drunk and having had violent and bloody fights with his wife who had threatened suicide. McDougal had also attempted to seduce some of the young women inmates (as, too, had his 17 year-old son who had been taken on as a workhouse schoolmaster).

McDougal's treatment of the dead was no better than that of the living. On one occasion, a dead baby was buried with an old man to save on the cost of a coffin. Babies born in the workhouse were rarely baptised as this cost a shilling a time. Any that subsequently died in infancy were declared to have been stillborn to avoid any awkward questions arising about their lack of baptism. Another revelation concerned Hannah Joyce, an unmarried mother whom the McDougals knew had previously been accused of infanticide. While at Andover, her five-month child died suddenly, although according to medical evidence, this was apparently from natural causes. However, a few days afterwards, the McDougals presented Hannah with with her baby's coffin and forced to carry it a mile on her own to the churchyard for an unceremonious burial.

The Select Committee's report, published in two huge volumes in August 1846, criticized virtually everyone involved in the scandal. The McDougals were found to be totally unfit to hold such posts; the Guardians had failed to visit the workhouse and had allowed the inmates to be underfed; Assistant Commissioner Parker, although competent in his everyday duties, had placed too much confidence in the Andover guardians; the Poor Law Commissioners had dismissed Parker and Day in an underhand manner and had mishandled the whole affair. Although no direct action was taken against the Commissioners as a result of the report, it undoubtedly led to its abolition the following year when the Act extending its life was not renewed. In its place, a new body — the Poor Law Board — was set up, which was far more accountable to Parliament.

The Andover Guardians appear to have come out of the affair little the wiser. The master appointed as successor to McDougal was a former prison officer from Parkhurst gaol. After only three years in the post, he was dismissed for atking liberties with female paupers.

Staff

Inmates

Records

Note: many repositories impose a closure period of up to 100 years for records identifying individuals. Before travelling a long distance, always check that the records you want to consult will be available.

- Hampshire Record Office, Sussex Street, Winchester SO23 8TH. Relatively few records survive — holdings include Guardians' minute books (1835-1930); Ledgers (1835-1930); Letter books (1846-1930); Papers relating to the workhouse scandal (1845-6); etc.

Bibliography

- The Scandal of the Andover Workhouse by Ian Anstruther (1973).

- The Workhouse by Norman Longmate, (2nd edition) 2003.

Links

Unless otherwise indicated, this page () is copyright Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.