South Dublin, Co. Dublin

Up to 1838

In 1703, an Act of the Irish Parliament provided for the setting up of a House of Industry in Dublin 'for employing and maintaining the poor thereof' (O'Connor, 1995). A workhouse was subsequently erected south of the River Liffey on land at the south of (Saint) James's Street and was administered by a body called 'The Governor and Guardians of the Poor' whose members included the Lord Lieutenant, the Lord Mayor, the Lord Chancellor, the Protestant Archbishop of Dublin, sheriffs, Justices of the Peace, and members of the Corporation. This body, which met monthly, had powers to place people in the workhouse, and to discipline those already there if they disobeyed workhouse regulations. Punishments could include flogging, imprisonment or deportation.

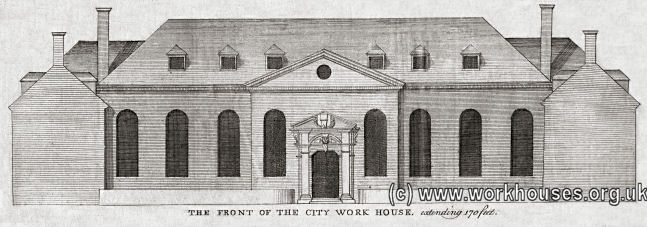

Dublin City workhouse, 1762

The main classes of inmate were 'sturdy beggars', 'disorderly women', the old and infirm, and orphan children. Up to 100 men and 60 women slept in bunk-like beds crammed into the workhouse cellars which were 240 feet (75 metres) long by 17 feet (5 metres) wide. The diet was made up of bread, milk, porridge, gruel, and 'burgoo' which was oatmeal in cold water seasoned with salt and pepper.

The Governors also provided care for abandoned children aged between 5 and 16, and could apprentice them out. A further Act in 1730 extended this role to cover all foundling children and a substantial part of the workhouse was allocated to this, with the workhouse being renamed the Foundling Hospital and Workhouse of the City of Dublin.

In 1772, the establishment's functions of the House of Industry and Foundling Hospital were separated and placed under separate management. A new House of Industry was set up on a site at the north side of the Liffey, leaving the existing premises continuing to operate as a Foundling Hospital.

The subsequent growth of the Foundling Hospital is illustrated by the following figures:

- 1702 - 260 children were admitted, and the number increased annually, especially after 1740.

- 1757 - 700 infants had been taken in yearly in the three previous years.

- 1796 - in the six years ending 1796, 12,786 infants were admitted.

- 1797-1818 - in twenty-one years, 43,254 infants were admitted.

The Foundling Hospital's popularity was no doubt due, at least in part, to its no-questions-asked policy. At one of its gates, there was a basket fixed to a revolving door. Someone wishing to leave a child anonymously could place it there, ring the porter's bell, and then depart. However, in the mid-1790s, the fate of the children left the Hospital started to come under scrutiny. The very large proportion of the children admitted who shortly after admission died attracted attention on several occasions. In the period 1791-1796 a total of 5,216 infants were sent to the infirmary with a solitary one recovering. In the March quarter of 1795, of the 540 children received into the Foundling Hospital, no less a number than 440 died. In 1797 a Committee of the Irish House of Commons was appointed to inquire into the management of the establishment. The Report was a most damning document.

It appears the children were "stripped" when sent up to the Infirmary (to die), and had the old clothing that they came into the House in put on them. That they were then laid, five and six huddled and crushed together, in the receptacles called cradles, "swarming with vermin," and they were then covered over with filthy and dirty blankets, which had been "cast" as unfit for use.

The particular feature in the working of this institution, it appears, was "The Bottle." The Hospital Nurse deposed when examined on oath by the Committee that a medicine called significantly "The Bottle" was handed round to them all at intervals indiscriminately. She did not know what was in it, but supposed it was a "composing draught," for "the children were easy for an hour or two after taking it." The surgeon, when he did come, always asked if she had given them "The Bottle," but asked no other questions. The surgeon knew all too well what the bottle was made up of, and that the children derived assistance from its contents. They were being assisted to die.

The Irish House of Commons adopted the recommendations of the Committee to reform the government of the Foundling Hospital. The new Corporation of Governors came into office in 1798, under a special Act of Parliament, and the Foundling Hospital was "reformed." However, things appeared to improve little. In 1829, the English House of Commons received information of continuing malpractices. Of 52,150 children admitted during 30 years ending January, 1826, 14,613 died in hospital while infants, 25,859 were returned as dead at nurse in the country, 730 died in the infirmary, 322 more who had been sent into the country for their health. In all, 41,524 died. The House unhesitatingly recommended the closing of the hospital and new admissions ceased in 1831. During the 1830s, the Hospital continued in operation supporting its existing inmates until they left, mostly through completion of an apprenticeship. By 1839, some 4,258 children, apprentices, and adult invalids were still counted as being dependent on the institution.

South Dublin workhouse site, 1836

After 1838

South Dublin Poor Law Union was formally declared on the 6th June 1839 and covered an area of 69 square miles. Its operation was overseen by an elected Board of Guardians, 33 in number, representing its 9 electoral divisions as listed below (figures in brackets indicate numbers of Guardians if more than one):

Co. Dublin: South City (18), Clondalkin (2), Donnybrook (2), Palmerstown (2), Rathfarnham (2), Rathmines (2), Tallaght (3), Whitechurch (2).

The Board also included 11 ex-officio Guardians, making a total of 44. The population falling within the Union at the 1831 census had been 182,767 with Divisions ranging in size from Whitechurch (population 2,921) to South City (140,000).

The part of Dublin to the north of the River Liffey was formed the separate North Dublin Poor Law Union.

The Poor Law Commissioners published a map of the new South Dublin union in their 1840 Annual Report:

The existing House of Industry and Foundling Hospital were adapted under the supervision of the Commissioners' architect George Wilkinson. The building work cost £5,608 plus £4,591 for fittings etc. It was intended to accommodate up to 2000 inmates as follows:

- 250 aged and infirm males

- 200 able-bodied and partially infirm males

- 350 boys

- 350 aged and infirm females

- 300 able-bodied and partially infirm females

- 350 boys

- 200 sick in the hospitals and violent lunatics in cells

The new workhouse accommodation was formally declared fit for the reception of paupers on 25th March, 1840, with the first admissions taking place on April 24th. The layout of the site soon after its conversion is shown on the 1849 map below:

The workhouse hospital facilities gradually expanded at the south of the site as shown on the 1907 map below.

South Dublin workhouse site, 1907.

In 1895, the workhouse was visited by a "commission" from the British Medical Journal investigating conditions in Irish workhouse infirmaries. Their report noted that South Dublin had separate infirmaries for Roman Catholic and Protestant patients, staffed respectively by nuns (Sisters of Mercy) and deaconesses, with a large number of pauper inmates acting as nursing assistants. Although some of the deaconesses had been trained at Tottenham Hospital, the nuns lacked any formal nursing training. The nuns also only worked during the daytime, and acted only in a supervisory role in the male wards. A total of thirteen nuns and around half a dozen deaconesses had charge of more than a thousand patients, with some wards being "distinctly overcrowded". Further details are available in the full report. The BMJ's revelations contributed to the introduction of significant improvements in the standard of Irish workhouse nursing, with the employment of pauper inmates as nurses ending ending after the passing of 1898 Local Government Act.

In 1916, the workhouse was occupied by rebel forces and during the subsequent fighting a member of the nursing staff was accidentally killed.

In 1918, the North Dublin union was amalgamated with South Dublin, the joint union being named the Dublin Union and based at the former South Dublin site. In 1920, the old North Dublin workhouse was taken over for military use.

Following the creation of the Irish Free State in 1922, boards of guardians were abolished except for those in Co. Dublin, which continued in operation until 1931. The James's Street site continued to develop as a municipal hospital and was renamed St. Kevin's. Up until 1935, the hospital was the main provider of maternity hospital facilities for women at the St Patrick's Mother and Baby Home at Pelletstown.

In 1971, St Jevin's was amalgamated with some of the smaller voluntary hospitals in the city and a new hospital was built at the James's Street site, which became known as St. James' Hospital.

The northern part of the original South Dublin workhouse site is now occupied by Trinity College, with St James' Hospital lying at the south. One block of the original buildings, dating from about 1750, still survives at the west of the site. It comprises a three-storey block at its northern end, said to have been used as the workhouse Master's residence. This is linked to a long two-storey block running north south.

South Dublin former Master's house from the north-east, 2002

© Peter Higginbotham.

South Dublin former workhouse buildings from the south-east, 2002

© Peter Higginbotham.

Some of the older hospital buildings remain at the north-east of the St James' Hospital site.

South Dublin hospital buildings from the north-west, 2002

© Peter Higginbotham.

Excavations for new buildings on the older part of the site now occupied by Trinity College have revealed the existence of the original Foundling Hospital basement. It is planned to preserve this historic structure under the new buildings.

In 2018, the new National Paediatric Hospital was being built at the western end of the original site, where the Kilmainham Sheds and RC Church are marked on the above 1907 map.

Pelletstown School

The South Dublin union operated a separate poor law school at Pelletstown, on the north side of the Navan Road, alongside Dublin's Phoenix Park. The North Dublin union's school, St Vincent's Home, stood a few hundred yards away to the south-east. In 1914, the two schools housed a total of 635 children.

South Dublin workhouse school site, 1907.

In 1910, the operation of the Pelletstown School was taken over by the Daughters of Charity. In 1919, in the wake of the merger of the two Dublin unions, the Pelletstown site took on a broader role. It was to cater for all mothers and infants; motherless children; all healthy children under the age of five; and all sick children such as the medical officers considered would be suitably treated there. It was at this point that it began to become a home for mothers and babies, though not necessarily confined to unmarried mothers, and adopted the name of the St Patrick's Home. The care of the older children was transferred to former North Dublin Union School, a short distance away on the opposite side of the Navan Road, also run by the Daughters of Charity.

Inmates

Records

Note: many repositories impose a closure period of up to 100 years for records identifying individuals. Before travelling a long distance, always check that the records you want to consult will be available.

- National Archives of Ireland, Bishop Street, Dublin 8.

- The South Dublin workhouse admission/discharge registers are now searchable online on [an error occurred while processing this directive] (subscription required).

Bibliography

- Corrigan, Frank (1976) Dublin Workhouses During the Great Famine (Dublin Historical Record, XXIX, No. 2, 59-65.

- Crossman, V (2006) Politics, Pauperism and Power in Late Nineteenth-century Ireland

- Gray, P (2009) The Making of the Irish Poor Law, 1815-43

- O'Connor, J (1995) The Workhouses of Ireland

Links

Unless otherwise indicated, this page () is copyright Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.