Workhouse Food

|

For an in-depth exploration of workhouse food, including lots of original menus and recipes, and every other aspect of workhouse life, check out The Workhouse Cookbook by Peter Higginbotham. ISBN 978-0-7524-4730-8 — Order via your local bookseller or online from Amazon UK. |

Food in the Parish Workhouse

The diet fed to workhouse inmates was often laid down in great detail. For example, the rules for the parish workhouse of St John at Hackney in the 1750s stipulated a daily allowance of:

2 Ounces of Butter,

4 Ounces of Cheese,

1 Pound of Bread,

3 Pints of Beer

Weak or "small" beer was widely consumed by both adults and children, both for its flavour and also as an alternative to water whose quality could be very variable. Many workhouses made their own beer and had a brewhouse specifically for this purpose.

More often than not, meals followed a weekly rota, with meat featuring on only a limited number of "meat days". The weekly menu at Hertford in 1729 comprised:

| Breakfast | Dinner | Supper | |

| Sunday | Bread & Cheese | Meat | Broth |

| Monday | Broth | Pease-Porridge | Bread and Cheese |

| Tuesday | Bread & Cheese | Hasty-Pudding | Bread and Cheese |

| Wednesday | Bread & Cheese | Meat | Broth |

| Thursday | Broth | Frumety | Bread and Cheese |

| Friday | Bread & Cheese | Ox-Head | Broth |

| Saturday | Broth | Hasty-Pudding | Bread and Cheese |

N. B.. None are Stinted as to Quantity, but all eat till they are satisfy'd.

Workhouse diets are often thought of as being very plain and meagre but this was often far from the truth. At Brighton in 1834, the 336 workhouse inmates were provided with three meals a day with no limits on quantity. Men received two pints of beer a day, children one pint, and women a pint of beer and a pint of tea. There were six meat dinners in the week and the inmates were served at table with the governor carving for the men and boys, and the matron for the women and girls. The full diet is shown below.

| BREAKFAST | Women: One pint of tea, with bread and butter. Men, boys and girls: Bread and gruel (of flour and oatmeal) excepting some old men, who are allowed a pint of tea, with bread and butter. |

| DINNER | Monday: Pease soup, herbs, &c. with bread; men and women a pint of table-beer; boys about half a pint. Tuesday: Beef and mutton puddings, with vegetables; the beer, &c., same as Monday. Wednesday: Boiled beef and mutton (sometimes pork with it), hard puddings, bread, vegetables, &c.; beer same as before. Thursday: Mutton and beef-suet puddings; beer same as before. Friday: Beef and mutton puddings, with vegetables; beer same as before. Saturday: Irish stew-meat, potatoes, herbs, &c.; beer same as before. Sunday: Boiled beef and mutton (sometimes pork with it), hard puddings, bread; vegetables, &c.; beer same as before. |

| SUPPER | Women: One pint of tea, with bread and butter or cheese. Men and boys: Bread and butter or cheese; men, one pint of beer or tea each; boys, about half a pint. Girls and small children: Bread and butter; drink, milk and water. |

In 1899, an official of the Scottish Local Government Board, William Penney, suggested that the excessive consumption of tea amongst female workhouse inmates was to blame for the number of pauper lunatics.

Food in the Union Workhouse

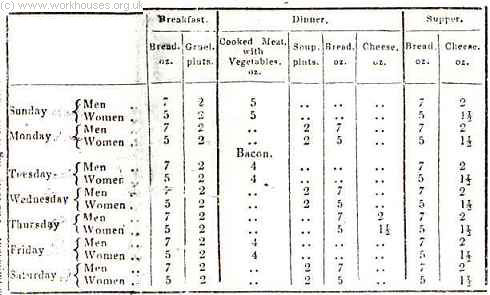

In 1835, the Poor Law Commissioners issued six sample dietary tables for use in union workhouses. Each Board of Guardians then used one of these tables as the basis for the particular diet in their own workhouse, with any variations subject to the agreement of the Commissioners. Here is the dietary used at Abingdon workhouse:

Abingdon workhouse dietary, 1836

Children and the aged or infirm had a slightly different diet, usually with more meat-based meals, and with inclusion of milk or tea. From 1856, special diets could also provided for children aged from two to five, and from five to nine. Special or medical cases might require extra or alternative food. Thus, each workhouse had to cope with at least seven classes of diet for the various categories of inmate, each carefully measured to comply with the regulations.

On admission, each inmate was assigned to a particular class of diet. The designations varied over the years — the one shown below was in use in the 1860s at the East Ashford Union workhouse:

| Class 1 | Able-bodied men |

| Class 2 | Old and Infirm Men |

| Classes 3 and 4a | Youths from 6 to 16 years |

| Class 4b | Boys from 2 to 6 years |

| Class 5 | Able-bodied women |

| Class 6 | Old and infirm women |

| Classes 7 and 8a | Girls from 6 to 16 |

| Class 8b | Girls from 2 to 6 years |

| Class 9 | Infants |

From 1900, the following scheme was generally used:

| Class 1 | Men not employed in work |

| Class 1A | Men employed in work (as 1 but with an additional meal on weekdays) |

| Class 2 | Infirm men not employed in work |

| Class 2A | Infirm men employed in work (as 1 but with an additional meal on weekdays) |

| Class 2B | Feeble infirm men (as 1 but with an additional meal on weekdays) |

| Class 3 | Women not employed in work |

| Class 3A | Women employed in work (as 1 but with an additional meal on weekdays) |

| Class 4 | Infirm women not employed in work |

| Class 4A | Infirm men employed in work (as 1 but with an additional meal on weekdays) |

| Class 4B | Feeble infirm men (as 1 but with an additional meal on weekdays) |

| Class 5 | Children aged from 3 to 8 |

| Class 6 | Children aged from 8 to 15 |

| Class 7 | Children under 3 |

| Class 8 | Sick diets |

The main constituent of the workhouse diet was bread. At breakfast it was supplemented by gruel or porridge — both made from water and oatmeal (or occasionally a mixture of flour and oatmeal). Workhouse broth was usually the water used for boiling the dinner meat, perhaps with a few onions or turnips added. Tea — often without milk — was often provided for the aged and infirm at breakfast, together with a small amount of butter. Supper was usually similar to breakfast.

The mid-day dinner was the meal that varied most, although on several days a week this could just be bread and cheese. Other dinner fare included:

- pudding — either rice-pudding or steamed suet pudding. These would be served plain. In later years, suet-pudding might be served with gravy, or sultanas added to make plum pudding particularly when served to children or the infirm.

- meat and potatoes — the potatoes might be grown in the workhouses own garden; the meat was usually cheap cuts of beef or mutton, with occasional pork or bacon. Meat was usually boiled, although by the 1880s, some workhouses served roast meat. There was some scope for local variation, for example some unions in Cornwall were allowed to substitute fish for meat. From 1883, all workhouses could if they wished serve a fish dinner once a week.

- soup — this would usually be broth, with a few vegetables added and thickened with barley, rice or oatmeal.

Although healthy in some respects, for example sugar was rare in the workhouse diet until the 1870s, it was often created from the cheapest ingredients. Milk was often diluted with water. Fruit was a rarely included.

The Quality of the Food

The quality and quantity of food in the workhouse diet was the subject of regular comment and debate. In 1841, Baxter condemned the workhouse diet as being inferior to that given to transported convicts. He also criticized the variability in the diets of different Unions, for example men in the Cirencester workhouse received a much smaller weekly allowance than men in the London workhouses.

The reputation of workhouse food suffered a blow in 1845 when, due to an administrative error, the inmates at Andover workhouse were receiving less than the amount specified in their dietary. As a result, a scandal erupted after male inmates were discovered to have been fighting over scraps of decaying meat on the bones they were meant to be crushing.

Will Crooks, a workhouse inmate in his childhood, later rose to become Chairman of the Poplar Board of Guardians. In 1906, he recounted his first visit as a Guardian to the Poplar workhouse:

It was not only the inmates who criticised the food. A local surgeon visiting the kitchens of the Sheffield union workhouse in 1896 was bold enough to sample the day's menu:

Research by the Poor Law Board's Medical Officer, Dr Edward Smith, found wide differences in the recipes used by workhouses for even basic foods such as gruel. In an effort to increase standardization, Smith published "formulae" for a number of common dishes. The examples below are from around 1870, by which time more milk and sugar and even luxuries such as "sweet dip" were included.

- Pea-soup, to make a pint—

- Meat (as shin of beef), 3 oz; bones, 1 oz; peas, 2 oz; potato and other fresh vegetables, 2 oz; dried herb and seasoning; meat liquor.

- Barley-soup, or meat broth, to make a pint—

- Meat, 3 oz; bones, 1 oz; Scotch barley, 2 oz; carrots, 1 oz; seasoning and meat liquor.

- Broth, to make a pint—

- Meat liquor, 1 pint; barley, 2 oz; leeks or onions, 1 oz; parsley and seasoning.

- Suet-pudding (baked or boiled), to make one pound—

- Flour (good seconds), 7 oz to 8 oz (according to the quality of the flour and the thickness desired); suet, 1¼ to 1½ oz; skimmed milk, 2 oz; salt.

To be served with gravy or sweet dip. - Rice-pudding, to make one pound—

- Rice, 3oz; suet, ½ oz; sugar ½ oz; skimmed milk, ½ pint; spice and salt.

- Rice-milk, to make one pint—

- Rice, 2oz; new milk, ½ pint; sugar, ½ oz; allspice and salt.

- Meat-pudding, to make one pound—

- Flour, 6 oz; suet, 1 oz; uncooked meat, 4 oz; meat liquor and seasoning.

- Meat and potato-pie, to make one pound—

- Flour, 3½ oz; suet or other fat, ½ oz; uncooked meat, 3 oz; potato 7 oz; onions, seasoning and meat liquor.

- Potato hash or Irish stew, to make one pint—

- Uncooked meat, 3 oz; potatoes, 12 oz; onions, 1½ oz; meat liquor and seasoning.

- Gruel, to make one pint—

- Oatmeal, 2 oz; treacle, ½ oz; salt and sometimes allspice; water.

- Oatmeal-porridge, to make one pint—

- Oatmeal, 5 oz; water and seasoning. To be eaten with milk.

- Milk-porridge, to make one pint—

- Oatmeal, 2 oz; milk 2/3 pint; water, salt.

- Tea, to make ten pints—

- Tea, 1 oz; sugar, 5 oz; milk, 1 pint.

The Workhouse Cookbook

By the 1890s, there were increasing complaints about the fixed-ration dietary system. By this time, most workhouse inmates were the elderly or sick who were found the food difficult to eat. Bread, in particular, was being thrown away in large quantities since the regulations required that each inmate had to be given their full serving, whether they wanted it or not.

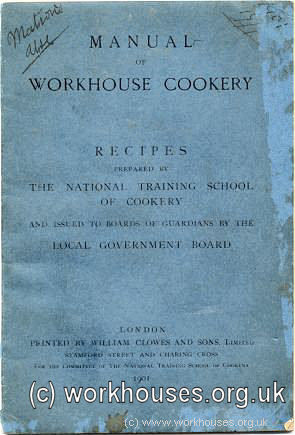

In 1900, the Local Government Board conducted a major overhaul of the workhouse dietary. It enabled unions to compile their own weekly menus from a range of about fifty dishes or "rations". In 1901, an official workhouse cookery book was compiled by the National Training School of Cookery to show workhouse cooks how to produce the new dishes to a uniform standard. The new recipes included dishes such as batter pudding, bread pudding, plain cake, seed cake, dumplings, fish pie, fruit pudding, golden pudding, pasties, potato pie, pease pudding, rice pudding, roly-poly pudding, sago pudding, semolina pudding, sea pie, shepherd's pie, haricot soup, lentil soup, pea soup, and... gruel.

Workhouse cookery book, 1901.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Haricot soup recipe, 1901.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The Manual of Workhouse Cookery is reproduced in its entirety in The Workhouse Cookbook.

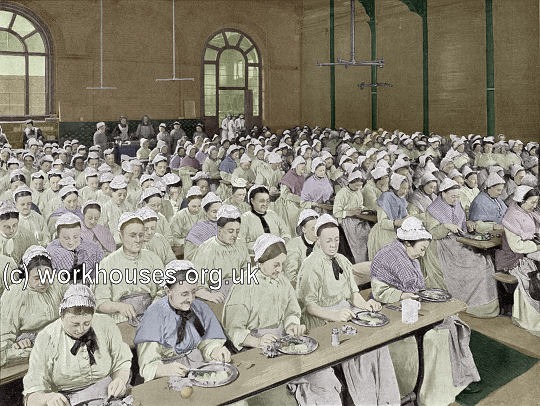

Workhouse Dining Halls

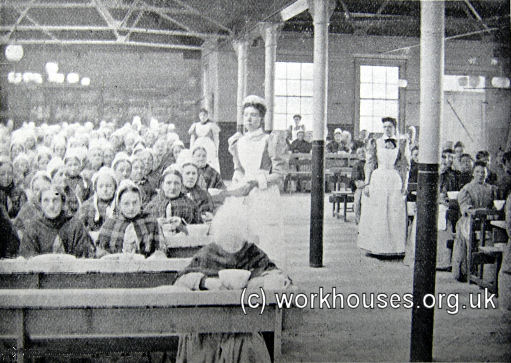

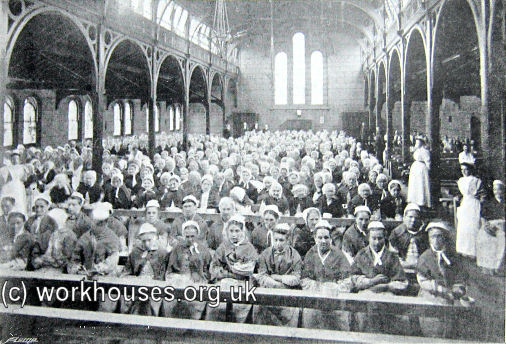

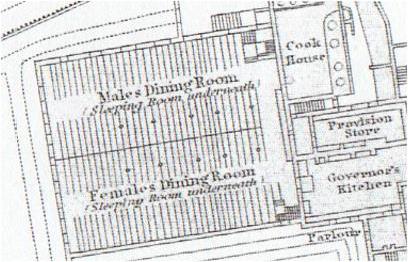

In larger workhouses, inmates commonly sat in rows all facing the same way, in some cases with separate men's and women's dining halls.

St Marylebone workhouse men's dining room, 1900.

© Peter Higginbotham.

St Pancras workhouse women's dining room, 1897.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The picture below shows the St Pancras workhouse kitchen, which lay at the other side of the dining room's rear wall. The food was cooked in industrial quantities.

St Pancras workhouse kitchen, 1897.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Poplar workhouse dining hall, c.1903.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Holborn Mitcham workhouse old women dining, 1896.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Map of Manchester workhouse dining room, 1848

Dining halls were equipped with scales so that inmates could get their food weighed in front of witnesses if they thought it was below the regulation weight. Inmates who took advantage of this provision were presumably not too popular with the workhouse staff.

Until the 1860s, workhouse food was often served on wooden trenchers - wooden boards with a shallow, hollowed-out area to hold the food. The supply of eating utensils was variable, though from the 1860s a knife, fork and spoon were usually provided. Earthenware tableware eventually became the norm - the illustration below shows a typical bowl and mug, each able to hold up to two pints. Crockery and cutlery were usually marked with the name of the union to deter theft.

Workhouse bowl, spoon, and mug.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Workhouse Kitchens

The kitchen in a parish workhouse would be a fairly typical domestic affair, perhaps with an open range over which pots were hung.

By the 1830s, however, the new generation of union workhouse buildings would normally be fitted with a closed range or 'kitchener' where an enclosed fire heated a hotplate above and one or more ovens to each side which could be used for baking bread or roasting meat.

For workhouses with large numbers of inmates, fairly elaborate kitchen facilities were required. A visitor to Manchester's Chorlton union workhouse in 1881 recorded:

The technology used in workhouse kitchens also evolved. The coal and wood used to fire the traditional kitchen range were joined by gas and steam which both offered clean and efficient sources of heat. Steam was particularly versatile — not only did it provide heat for cooking and for warming the building, but could also power mechanical devices such as pumps, laundry equipment, and dynamos. By the 1860s, the Victorian talent for mechanical and engineering inventiveness was beginning to make its mark on institutional kitchens such as those found in larger workhouses. All manner of novel machines for preparing and cooking industrial quantities of food were devised and heavily advertised in the trade press of the day.

Kitchen equipment advertisement, c.1870.

© Peter Higginbotham.

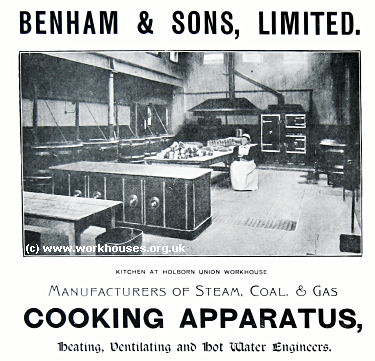

Benham & Sons advertisement, c.1901.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Unless otherwise indicated, this page () is copyright Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.