Leeds, West Yorkshire

Up to 1834

The first Leeds parish workhouse was opened in 1638 at the north-east corner of the junction of Lady Lane and Vicar Lane. It appears to have fallen out of use, and from 1705 to 1726 the building was used by the Leeds Charity School.

Leeds Lady Lane workhouse site, 1847.

In March 1725, the Leeds Vestry decided to re-establish the workhouse under a new, stricter regime, with Robert Milnor as the workhouse master. Poor relief intended to be offered only to those entering the workhouses, and hard work being required of the inmates. All the town's 'Charity Children' in receipt of poor relief were also to be taken into the workhouse. The Vestry employed Shubaal Speight, his wife, and their two sons at £50 a year to attend the workhouse and to 'teach the Children and others to spin with the dutchwheel and to card to it.' Work was also to be sought from outside employers. However, difficulties in finding suitable contracts, and the refusal of inmates to work, soon put the workhouse into debt and it closed in January 1728.

The table below shows the workhouse dietary in October 1726.

| Breakfast | Dinner | Supper | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sun | Bread and Beer | Beef and Broth | Milk Porridg |

| Mon | Beef broth | Rice milk | Milk Porridg |

| Tue | Milk Porridg | Plumb Puddings | Milk Porridg |

| Wed | Bread and Cheese | Beef and Broth | Milk Porridg |

| Thu | Beef broth | Potatos | Milk Porridg |

| Fri | Bread and Beer | Rice milk | Milk Porridg |

| Sat | Water porridg and treacle | Peas Porridg |

In September 1738, the workhouse re-opened again under a more benign management. The Vestry Committee Minutes list typical cases: Mary Scholfield was to be admitted 'till she be well'; George Coare, who was 'aged over seventy', was taken into the workhouse after 'having the misfortune in Breaking his Ribs and Never likely to recover'.

The workhouse buildings were extended in 1740 with the addition of a workroom, granary, washhouse, brewhouse, infirmary and, by 1771, lunatic cells. A separate page lists the Leeds workhouse rules from 1771.

Eden, in his 1797 survey of the poor in England, reported of Leeds that:

Table of diet: Breakfast—every day, milk pottage and bread. Dinner—Sunday, mutton, potatoes, broth, bread and beer; Monday, Friday, rice milk, bread and beer; Tuesday, flour dumplins and beer; Wednesday, bread, cheese and beer; Thursday, potatoes, broth, bread and beer; Friday, rice milk, bread and beer; Saturday, drink pottage and bread. Supper—Sunday, bread and broth; Thursday, bread and broth or beer only; other days, milk pottage and bread. Of wheaten cake 3lbs. are divided into 8 parts, viz., 2 parts of 7oz. each for 2 men, 4 of 6oz. for 6 women, and 2 of 5oz. for 2 children. 1lb. of rice, with 10oz. of sugar, with cloves, pepper, salt, etc., are allowed to 20 persons. Each adult has 14oz. and each child 8oz. of paste for dumplins. 20 persons have 1 gallon of milk for milk pottage, and each person has one-third of a quart (ale measure) of beer at dinner except on Saturdays. Adults have 6oz. of cheese each, children 4oz. The cheese is worth about 4½d. per lb. At Easter and Whitsuntide veal and bacon are provided for dinner and roast beef at Christmas, and at each of these seasons each pauper receives 1lb. of spiced cake. The prime meat is purchased for the house; every person finds his own knife and fork, and is served with dinner in the dining room. In general, the stores when delivered are carried up to the lodging rooms. No.24, however, of the rules observed in the Workhouse, adopted on May 9th, 1771, requires "that all the Poor in this house who are able to attend prayers, sit decently at their meals, avoid talking and make no attempt to go out of the dining-room till thanks are returned; and, in default of any of these particulars, to lose their next meal"; and No.29 provides for the punishment of any person carrying any bread, cheese, or other provisions (without leave from the master) out of the common dining-room. It is but justice to add that Mr. Linsley, the master of the Workhouse, is in every respect highly qualified for the very arduous and complicated duties of his important office, in the discharge of which he has happily been able to render those under him contented, without permitting them to be idle, and to provide for their wants without losing sight of economy. His humane disposition, and firm, even temper, make him beloved, respected and obeyed with cheerfulness, and (what is seldom to be met with in houses of this description) the Poor under his care live in perfect harmony among themselves. Their earnings amount to about £150 a year, exclusive of work performed for the immediate use of the house. The following other persons also receive relief, viz.: Regular Out-Poor, 415; casual Out-Poor, 251; militia men's families, 158.

The operation of poor relief in Leeds was by a body of overseers appointed under a provision in a Local Act of 1755 for lighting and cleansing the town.

After 1834

Leeds initially adopted a policy of non-cooperation with the New Poor Law. Its Local Act status exempted it from many of the provisions of the 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act. However, on 21st November 1844, the Poor Law Commissioners placed the township's poor relief administration under the control of a body called the Leeds Guardians. The Board assembled for the first time on 23rd December and elected John Cawood as Chairman and John Beckwith as Secretary.

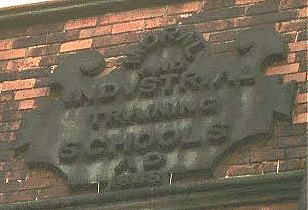

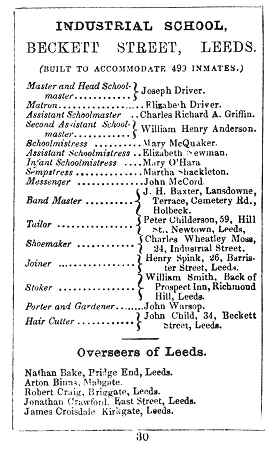

Moral and Industrial Training Schools

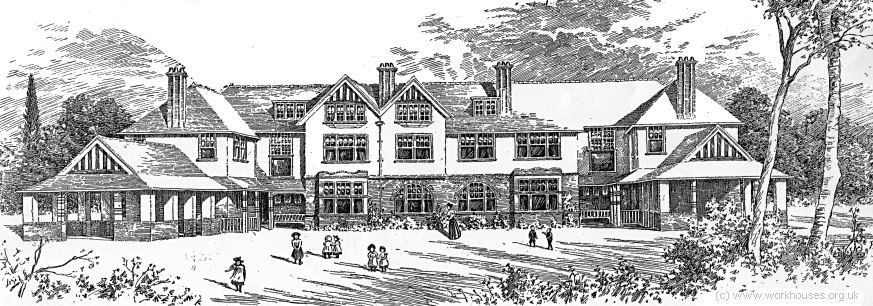

One of the first acts of the Leeds Guardians was the erection, in 1846-8, of the Moral and Industrial Training Schools, located on the north side of Beckett Street in Leeds

Leeds Moral and Industrial Training Schools, 1848.

© St James Hospital, Leeds.

Leeds Moral and Industrial Training Schools from the east, c.1865.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Leeds Moral and Industrial Training Schools, 2002.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Leeds Moral and Industrial Training Schools, 2002.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The school experienced early problems because of the ineffectualness of its headmaster, the Revd William Taylor Dixon, and also the Guardians' insistence that children should work at shoe-making for nine hours a day. Dixon resigned but his successor, the Revd Charles H Nicholls, fared little better. It was reported that he "allowed himself to get in such a state with the children that he foamed at the mouth." In October, 1853, another master of the school, Joseph Linsley Kirk, was accused of habitual drunkenness, swearing and fighting. After an inquiry, the schools rules and regulations were overhauled but Kirk and his wife remained in post.

The Beckett Street Workhouse

In the late 1840s, the old Lady Lane workhouse, which was still in use, was unable to cope the with the increasing demands being placed on it. This was exacerbated by an influx of Irish vagrants in the wake of the Great Famine.

Eventually, the Leeds Guardians agreed to erect a new workhouse, which was built in 1858-61 on a site adjoining the Training School. The architects were William Perkin and Elisha Backhouse who also designed Ripon workhouse.

The workhouse comprised a main block, infirmary, chapel, and "idiotic" wards. A large new infirmary was added to the site in 1872-4, followed by a nurses' home in 1893-4, an imbecile block in 1896-1900, casual ward in 1901-2, and a receiving block in 1905. The layout of the site is shown on the 1906 map below.

Leeds workhouse site, 1906.

Leeds workhouse from the south, c.1865.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The entrance block with its arched gateway stood on Beckette Street.

Leeds workhouse entrance block, early 1900s.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The long main block faced south-east towards Beckett Street.

Leeds workhouse infirmary.

© St James Hospital, Leeds.

Leeds main block from the east, 2001.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The dining-hall and kitchen were located at the centre rear of the main block. A laundry block lay just to the south.

Leeds dining-hall and kitchen block from the south, 2001.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The chapel at the south of the main building was part of the original workhouse construction.

Leeds chapel from the south, 2001.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The original infirmary, to the north of the chapel, had up to 140 beds, including some for the mentally ill.

Leeds workhouse infirmary.

© St James Hospital, Leeds.

A separate "idiotic" block was built in 1862-3 to the north-west of the chapel. Designed by Perkins and Backhouse, it was similar in appearance to the original infirmary. It was two storeys high, with male and female wards each having twenty beds, plus two for attendants. The ground floor on each side contained a day-room, and a small room, not padded, was adapted for dealing with violent cases. The walls of the wards were decorated with brightly coloured wallpaper to give a cheerful appearance. No running water or washing facilities were installed, however. The attendants on these wards were pauper inmates who received an evening ration of bread, cheese and beer on top of the ordinary diet of the 'idiotic' wards.

Leeds 'idiotic' block from the south, 2001.

© Peter Higginbotham.

In 1869, following the abolition of the Carlton and Barwick-in-Elmet Gilbert Unions, there was a reorganisation of poor law administration in the Leeds area. On 21st June, 1869, a new Leeds Poor Law Union came into being, replacing the Leeds Guardians. The new Union included the parishes of Chapel Allerton (represented by 2 guardians), Headingley-cum-Burley (6), Leeds (18), Potter Newton (2), Roundhay (1) and Seacroft (2), and had a total population of 117,566.

In 1872-4, a new 216-bed three-storey infirmary was erected at the west of the main workhouse. The building was extended in around 1878, with the addition of a further 139 beds. In 1892-4, an E-shaped nurse's home housing up to forty nurses was added at the west of the infirmary; it was heightened in 1903 and extended to the south-west in 1923-5.

A new laundry was erected in 1899 at the east of the dining-hall. It cost £12,000 and was designed by Thomas Winn, with machinery supplied by Messrs Bradford and Messrs Summerscales.

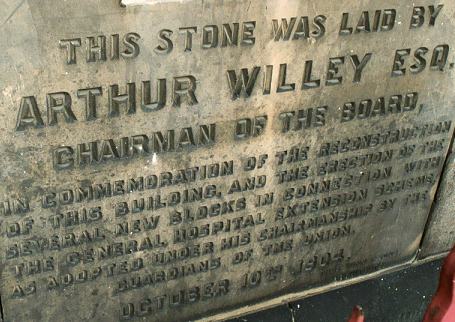

Winn was also the architect of a new casual ward block erected in 1901 on the Gledhow Road frontage at the north-west corner of the site. The foundation stone was laid on 22nd July 1901 by Tom Atkinson, Chairman of the union's Vagrant Wards Committee. The complex included men's and women's shelters, receiving rooms, examination rooms, and observation room, thirty sleeping cells for men and twenty for women, twenty stone-breaking cells, and a receiving officer's quarters. The official opening of the facility, by the Chairman the Guardians, Arthur Willey, took place on 14 July 1902, as reported at the time:

The members of the Board of Guardians and officials, accompanied by ladies, drove an open conveyances from the offices in South Parade to the new vagrant wards. In the planning of building isolation from other portions of the premises has been an important consideration, so the new structure occupies the extreme corner the estate, facing Gledhow Road. In another sense isolation is secured. To the confirmed tramp the society of kindred souls is a great attraction Of the ordinary vagrant ward. Here, however, the adoption of what is known as the "cell" system prevents communication.

On his arrival the tramp gets a bath — a luxury which he does not always appreciate. His dormitory is a clean cell, lined with white glazed bricks, and fitted up with a hammock. On the opposite side of a passage running through the suite of cells is a stone-breaking cell, in which he is obliged to break a certain quantity of stone in consideration of his night's shelter and food. The Board are about to adopt the "two nights" system, and for the care and attention bestowed upon him he will have to account for at least 12 hundredweight of stone. And there is no shirking of the work either. The stones have to be put through a perforated iron plate, and the size of the perforation is an adequate guarantee that the stones have been reduced to sufficiently small pieces.

Not all the Nomads are required to break stones. For a gentleman of delicate constitution or more refined upbringing there is the alternative of wood-cutting and oakum-picking. Women tramps, too, are set to the latter kind of work. That is accommodation for 44 males and 14 females, with separate entrances. A large one-storey labour shed has also being built at the rear of the vagrant block for the purposes of wood-cutting and other general work. The entire buildings have been provided at a cost of less than £13,000 pounds

Leeds casual wards from the north-west, 2009.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Leeds casual wards, 2009.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Leeds casual ward cell windows, 2009.

© Peter Higginbotham.

At the rear of the casual ward complex, the workhouse had its own small fire station. It was operated by members of the workhouse staff who were given training by the local fire brigade.

Leeds workhouse fire brigade, early 1900s.

© Peter Higginbotham.

In 1904, the Training Schools building underwent a "reconstruction" to convert it for use as a hospital block, as commemorated by a foundation stone, again laid by Chairman of the Guardians, Arthur Willey.

Leeds 1904 foundation stone, 2002.

© Peter Higginbotham.

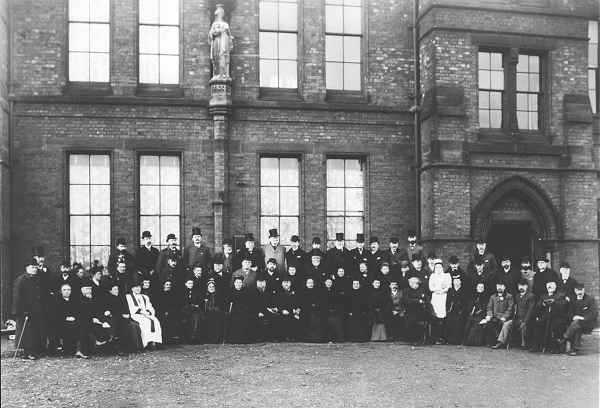

Leeds Union Board of Guardians.

© St James Hospital, Leeds.

Leeds Union Board of Guardians.

© St James Hospital, Leeds.

Leeds Union Diary.

© St James Hospital, Leeds.

Leeds Workhouse Female Inmates.

© St James Hospital, Leeds.

In March 1915, the Leeds Guardians offered the workhouse and infirmary to the War Office for the accommodation of sick and wounded soldiers. The existing workhouse inmates were transferred to the Hunslet workhouse and the Leeds premises became the East Leeds War Hospital. Wounded soldiers from the battle-front in France arrived in Leeds by train and were transferred to the hospital by a fleet of army and Red Cross Ambulances.

East Leeds War Hospital, c.1915.

© St James Hospital, Leeds.

The former workhouse later became part of St James' Hospital but is now the home of the Thackray Medical Museum.

Leeds workhouse from the cemetery opposite where many paupers were buried.

© St James Hospital, Leeds.

Leeds Scattered Homes and Central Home

To accommodate its pauper children, the Leeds Union adopted the scattered homes system pioneered in the 1890s by the Sheffield Union. Under this system, children were placed in "family" groups of fifteen to twenty children under the care of a house-mother in ordinary suburban houses.

The list of the premises used as homes varied a little over the years but included: 62 Belle Vue Road, 15 Banstead Terrace, 55 Brudenell Mount, 11 Claremont Grove, 19 Cross Green Crescent, 61 East Park Parade, 34 Hamilton Avenue, 24 & 43 Hartley Avenue 43 Hartley Crescent, 25 Hessle View; Leopold House, Leopold Street; 103 Markham Avenue, 12 Osmandthorpe Lane, 22 Seaforth Avenue, 24 Stanmore Place, 28 Strathmore Drive, 310 York Road, and 'Southfield' at Halton.

These homes were generally just ordinary terraced houses, such as the one at 11 Claremont Grove, shown below.

Leeds scattered home at 11 Claremont Grove, 2009.

© Peter Higginbotham.

A probationary home and administrative centre for the system was provided by the Central Home which was erected in 1901 on Street Lane in north Leeds. The Central Home, which could accommodate up to forty children, was designed by Percy Robinson. Its construction cost around £7,000.

Leeds Central Home site, 1906.

The ground floor included offices, kitchens, dining-room, children's day rooms, and covered playgrounds at the rear.

Leeds Central Home ground floor plan, 1900.

Girls's dormitories were located on the first floor and boys' on the second.

Leeds Central Home from the south — architect's drawing, 1900.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Leeds Central Home entrance from the east, c.1905.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Leeds Central Home from the south-east, 2006.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Leeds Central Home from the north, 2006.

© Peter Higginbotham.

A separate superintendent's house, office and stores stood near the entrance gates.

Leeds Central Home Superintendent's house, 2006.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The Street Lane premises are now used for commercial and residential purposes.

As well as the Central Home on Street Lane, a receiving home for new admissions operated for some years in a house at 113 Beckett Street, near the workhouse. It appears to have closed by 1911 and the building no longer exists.

Staff

- 1861 Census — Leeds Workhouse

- 1881 Census — Leeds Workhouse

- 1881 Census — Leeds Workhouse Vagrant Wards

Inmates

- Long-term workhouse inmates (1861)

- 1861 Census — Leeds Workhouse

- 1881 Census — Leeds Workhouse

- 1881 Census — Leeds Workhouse Vagrant Wards

Records

Note: many repositories impose a closure period of up to 100 years for records identifying individuals. Before travelling a long distance, always check that the records you want to consult will be available.

- West Yorkshire Archive Service (Leeds Office), Nepshaw Lane South, Morley, Leeds LS27 7JQ. Holdings include: Guardians' Minutes (1844-1930); Admissions and discharges (1843-7); Adoptions register (1895-1948); Bastardy register (1844-1930); etc.

Bibliography

- Anderson, Philip (1981) The Leeds Workhouse under the Old Poor Law, 1726-1834 (in The Thoresby Miscellany Volume 17, Part 2)

- Pennock, Pamela (1984) Leeds Moral and Industrial Training School, Leeds Union Workhouse and Leeds Union Infirmary (in The Thoresby Miscellany Volume 18, Part 2)

- Bedford, Paul and Howard, David N (1985) St James's University Hospital, Leeds - A Pictorial History.

Links

Acknowledgment

- Thanks to St James's Infirmary, Leeds, for use of archive pictures.

Unless otherwise indicated, this page () is copyright Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.