Christmas in the Workhouse

In the era of the parish workhouse, prior to 1834, Christmas Day was the traditional occasion of a treat for most workhouse inmates. In 1828, for example, inmates of the St Martin-in-the-Fields workhouse received roast beef, plum pudding, and one pint of porter each. In the Bristol workhouse in the 1790s, the Christmas Day (and Whit Sunday) dinner included baked veal and plum pudding. At the same date, Leeds workhouse inmates were given veal and bacon for dinner at Easter and Whitsuntide, roast beef at Christmas, and 1lb. of spiced cake each at each of these festivals. At Carlisle on Christmas Day the workhouse inmates were allowed roast mutton, plum pudding, best cheese, and ale.

However, in the new union workhouses set up by the 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act, things were rather different, at least to begin with. The Poor Law Commissioners ordered that no extra food was to be allowed on Christmas day (or any other feast day). The rules also stated that "no pauper shall be allowed to have or use any wine, beer, or spirituous or fermented liquors, unless by the direction in writing of the medical officer." Nevertheless, some unions chose to disregard the rules and celebrate Christmas in the traditional way. In Cerne Abbas, for example, the new workhouse's first Christmas dinner in 1837 included plum pudding and strong beer. At Andover, the inmates received bread and cheese on the previous "meat day" so as to save a ration of beef for Christmas day. Despite the lack of festive fare, Christmas Day was (along with Good Friday and each Sunday) one of the special days when no work, except the necessary household work and cooking, was performed by the workhouse inmates.

By 1840, the Poor Law Commissioners revised their rules to allow extra treats to be provided, so long as they came from private sources and not from union funds. Following the Queen's marriage to Prince Albert in 1841, the Victorian celebration of Christmas took off in a big way, with the importing of German customs such as Christmas trees and the giving of presents. Dickens' A Christmas Carol also raised the profile of the event. In 1847, the new Poor Law Board who succeeded the Poor Law Commissioners relented further and sanctioned the provision of Christmas extras from the rates.

By the middle of the century, Christmas Day (or more often Boxing Day, December 26th) had a became a regular occasion for the Guardians to visit the workhouse and dispense food and largesse. The workhouse dining-hall would be decorated and entertainments organised. The Western Gazette's 1887 report on the Christmas festivities in Chard is typical:

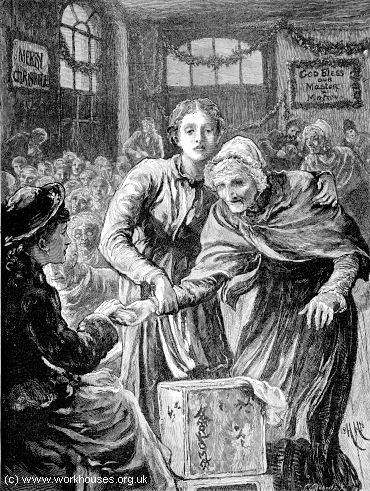

Even at Christmas time, though, some workhouse rules stayed firmly in force, such as the segregation of males and females seen in the 1874 illustration below of Christmas festivities in the Whitechapel workhouse.

Whitechapel Workhouse, Christmas 1874.

© Peter Higginbotham.

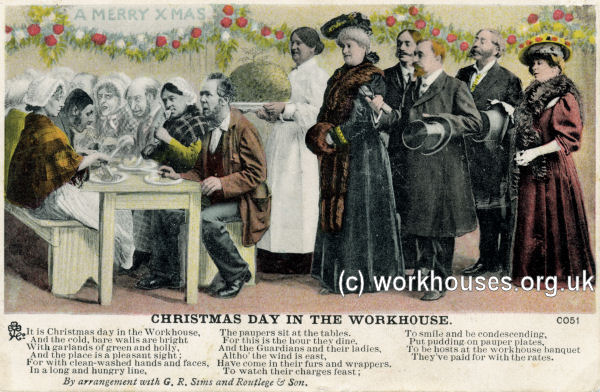

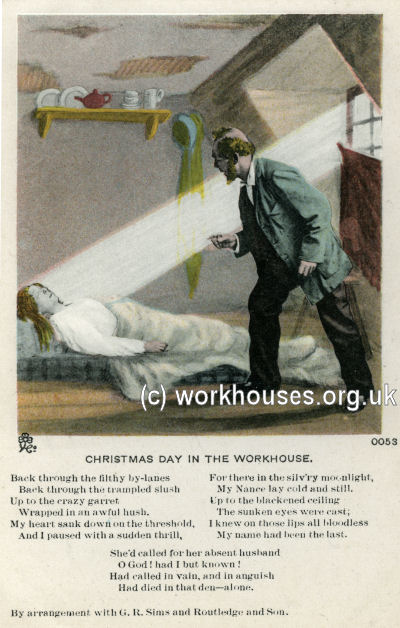

Such occasions were, however, seen by some as condescending and patronising. One of the best-known pieces of workhouse literature, the melodramatic ballad or monologue In the Workhouse: Christmas Day, was written from this standpoint. Its author, George R Sims, was a campaigning journalist specialising in stories on poverty and poor housing published in the series entitled How the Poor Live and then in a column in the new Sunday Referee.

In the Workhouse, Christmas Day.

© Peter Higginbotham.

His monologue, first published in 1877, tells the story of inmate whose wife had been refused out-relief the previous Christmas and had starved to death rather than enter the workhouse and be separated from him. Here are the ballad's opening stanzas:

It is Christmas Day in the workhouse,

And the cold, bare walls are bright

With garlands of green and holly,

Ad the place is a pleasant sight;

For with clean-washed hands and faces,

In a long and hungry line

The paupers sit at the table,

For this is the hour they dine.

And the guardians and their ladies,

Although the wind is east,

Have come in their furs and wrappers,

To watch their charges feast;

To smile and be condescending,

Put pudding on pauper plates.

To be hosts at the workhouse banquet

They've paid for — with the rates.

Oh, the paupers are meek and lowly

With their "Thank'ee kindly, mum's!'"

So long as they fill their stomachs,

What matter it whence it comes!

But one of the old men mutters,

And pushes his plate aside:

"Great God!" he cries, "but it chokes me!

For this is the day she died!"

Despite a number of factual flaws in its narrative (regulations allowed couples over sixty to have a room together, and the onus on the union to take in and feed anyone in case of "sudden and urgent necessity"), Sims's ballad became immensely popular. Click here to read the full version of Christmas Day in the Workhouse as the ballad is most popularly known.

Sentimental workhouse christmas scenes were also popular with graphic artists of the 1870s and 1880s, such as the one below by by Hubert von Herkomer which appeared in The Graphic in 1876.

Christmas in a Workhouse, 1876.

Christmas in a Workhouse, 1876.

© Peter Higginbotham. |

CHRISTMAS IN A WORKHOUSE

Once on a time, not long ago, Only some sixty years or so, Her skin was white as driven snow, Each lip a cherry; At least, so rapturous lovers said, And now these lovers all have sped, Gone to the City of the Dead, In Charon's Ferry. Too oft Life saddens towards its end, Yet helping hand of child or friend, And independent means, may lend Some compensation; But when Old Age, bereaved, distressed, Crawls to the Workhouse for its rest, Existence then must be at best A desolation. Most days are sad, but not quite all, For even the cheerless Workhouse hall, When dawns the Christmas festival, Looks bright and pleasant; And then the kindly fairy's last Best gift—the tea—in teapot cast, May bring to mind a far-off Past, A welcome Present! |

In the 1870s and 1880s, the temperance movement became influential in Britain and the Drink Reform League specifically campaigned for the banning of alcohol from workhouses. In 1884, the Local Government Board decreed that workhouse masters would be liable for the cost of any alcohol that was not supplied under medical instruction — a master at Islington subsequently faced a bill for over 200 gallons of port consumed by his nursing staff.

Fortunately, no such fate befell the traditional "plum pudding" served up to workhouse inmates. The following recipe for a Christmas pudding for 300 persons was kindly supplied by Pat Constable whose family includes several generations of workhouse master. She says that the recipe was perfected by her parents Lionel and Annie Williams who ran several institutions including the former Bridport workhouse in the 1940s. By this time, they were fortunate enough to have the benefit of a food mixer to help prepare the mixture.

WORKHOUSE CHRISTMAS PUDDING FOR 300

Ingredients:

- 36 lbs Currants 42lbs Sultanas

- 9 lbs Dates

- 9lbs Mixed Peel

- 26 lbs Flour

- 16 lbs Breadcrumbs (prepared)

- 24 lbs Margarine

- 26 lbs Demerara Sugar

- 102 lbs Golden Syrup

- 102 lbs Marmalade

- 144 Eggs

- 2lbs 10oz Mixed Spice

- 13 lbs Carrots (prepared)

Method:

Cream fat and flour in Hobart mixer to a fairly thin consistency. Mix breadcrumbs with chopped dates and add to fat mixture. Put shredded carrots and all dried fruit (washed) into separate bowl and mix thoroughly. Then gradually add the first mixture. Add brown sugar, stirring all the time. Add marmalade. Add spice and stir well. Add eggs, which have already been well beaten. Finally add the hot melted syrup.

N.B.

1 - Eggs are beaten in the Hobart mixer

2 - Wash all dried fruit in hot water before adding shredded carrots

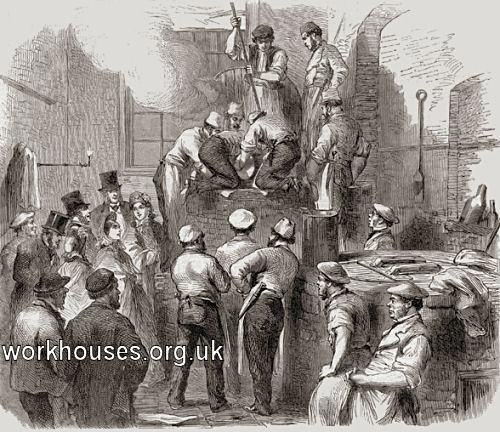

In December 1862, a monster Christmas pudding was made in the kitchens of St Marylebone workhouse. It was not for the inmates' consumption however, but was being sent to Lancashire mill workers who had been made unemployed by the 'cotton famine' resulting from the American Civil War.

Monster Christmas pudding being made at St Marylebone workhouse, 1862.

© Peter Higginbotham.

For cost-conscious keepers of the public purse, however, the Christmas pudding could still be a source of contention. At a meeting of the Newark Board of Guardians in December 1896, a heated debate ensued when it was revealed that a pudding for twenty-five inmates of the workhouse infirmary was to use 35lb of currants, 21lb of sugar, 30 eggs, and 20lb of raisins. One Board member calculated this would amount to 4lb of pudding per head whereas half that amount would surely suffice. However, a motion to reduce the quantities was declared out of order when it was pointed out the ingredients had been passed without comment at a previous meeting.

Woolwich workhouse dining-hall — Christmas Day, 1905.

© Peter Higginbotham.

By the early 1900s, workhouses were often on Santa's visiting list, as illustrated by this 1906 picture of a boys' ward at Belfast workhouse.

Belfast workhouse workhouse boys' dormitory, Christmas 1906.

The picture below of the Tarvin workhouse was kindly contributed by Steve Martin. The small boy is Steve's father Chris, son of the workhouse Master and Matron. The institution's GP, Dr W. Woodruff, is at the left of the picture.

Christmas at Tarvin workhouse, c.1928.

© Steve Martin

A well as Christmas itself, New Year's Day was often marked as shown in this 1897 illustration of the occasion in an unidentified workhouse by J. Barnard Davis.

New Year's Day in a Workhouse, 1897.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Bibliography

- Webb, Sidney & Beatrice (1910) English Poor Law Policy (London: Longman's, Green and Co.)

Unless otherwise indicated, this page () is copyright Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.