Religion in Workhouses

The 1601 Poor Relief Act placed responsibility for care of the destitute with the parish. The administration of poor relief was carried out through the parish committee, the Vestry, whose members included the parish priest and churchwardens. It is therefore not surprising that recipients of parish relief should be expected to follow the regular observances of the established Church as a mark of their gratitude in receiving such support.

With the gradual evolution of the workhouse during the seventeenth and early eighteenth century, regular attendance at church usually formed part of the rules that were formulated to govern the behaviour of workhouse inmates. At the St. Andrew's Holborn, Shoe-Lane, workhouse in the City of London, the regulations in 1732 specified that:

As the St Andrew's rules indicate, a visit to church could also provide an opportunity to illicitly stop off at an inn, something the workhouse authorities were keen to prevent. At Croydon in February 1753, following a complaint that "several of the Poor, let out of the House to hear Divine Service on Sabbath Days were frequently seen about Town, begging, and often drunk" it was ordered that "for the future, no Person thus scandalously behaving, should be suffered to go out of the House, on any pretext whatsoever."

Apart from church services, prayers and the saying of grace at mealtimes were part of the daily workhouse routine as seen in the 1810 rules at Stone in Staffordshire:

Similar provisions existed in the regulations devised for the running of union workhouses in the wake of the 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act.

— The Guardians may authorize any inmates of the Workhouse, being members of the Established Church, to attend public worship at a parish church or chapel, on every Sunday, Good Friday, and Christmas-day, under the control and inspection of the Master or Porter, or other officer.

- The Guardians may also authorize any inmates of the Workhouse, being dissenters from the Established Church, to attend public worship at any dissenting-chapel in the neighbourhood of the Workhouse, on every Sunday, Good Friday and Christmas-day.

The daily routine of prayers and graces was usually carried out by the workhouse master. In addition, each union was required to appoint a chaplain whose duties were:

2. To examine the children, and to catechise such as belong to the Church of England, at least once in every month, and to make a record of the same, and state the dates of his attendance, the general progress and condition of the children, and the moral and religious state of the inmates generally, in a book to be kept for that purpose, to be laid before the Guardians at their next ordinary meeting, and to be termed "THE CHAPLAIN'S REPORT."

3. To visit the sick paupers, and to administer religious consolation to them in the Workhouse, at such periods as the Guardians may appoint, and when applied to for that purpose by the Master or Matron.

Although the duties of a union workhouse chaplain could seem very modest, each appointment had to be approved by the Bishop of the local diocese in case it conflicted with the clergyman's other duties. Chaplains' salaries varied widely. Some were relatively well paid and could receive a salary on a par with that of rather more onerous full-time posts such as the workhouse master. One clergyman, writing in 1847, suggested that workhouse chaplains in Huntingdonshire received a very generous £150 per annum, while the wealthy Richmond Union in Yorkshire paid a mere £10 (Cousins, 1847). Whatever the expense of employing a chaplain, one attraction of doing so was that inmates did not have to be released to attend church services outside the confines of the workhouse.

The Poor Law Commissioners implicitly assumed that unions would appoint a chaplain from the Church of England. There was, however, considerable resistance to this in some areas. In some cases, Boards of Guardians decided that the expense of a chaplain outweighed any problems arising from inmates attending a local church. To try and persuade them otherwise, the Commissioners required that inmates should only be allowed out under strict supervision, marching to and from church in their workhouse uniforms. In areas such as Cornwall and the north of England where "dissenters from the Established Church" were most common, any pressure to appoint a Church of England chaplain was seen as an attempt to proselytise non-Anglican inmates and also to provide jobs for the clergy. Since dissenters were allowed to opt out of services, appointing a Church of England chaplain also appeared to be futile in unions where dissenters were in the majority. The Commissioners reluctantly agreed that non-Anglican inmates should continue to be allowed out on Sundays, so long as a certificate of church attendance for each attendee was signed by the officiating minister. Non-conformist ministers were increasingly allowed to hold services inside workhouses, invariably doing so without charge, much to the satisfaction of the guardians of such unions. Roman Catholic priests were not, however, welcomed into the workhouse — at least in England and Wales. Even in workhouses having a high proportion of Catholic inmates, such as Liverpool, the appointment of Catholic chaplains was vetoed. In Irish workhouses, however, Catholic chaplains were in the majority, with unions in some areas employing both a Protestant and a Catholic chaplain.

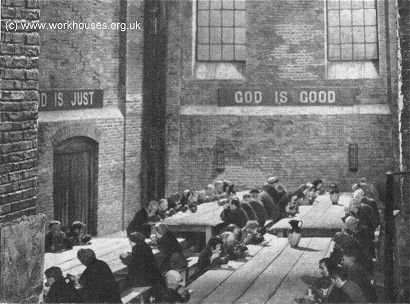

Most union workhouses originally utilised their dining-halls for religious services. The interior decor of such rooms might carry a reminder of how lucky the inmates were to be receiving poor relief.

Workhouse dining hall

© Peter Higginbotham

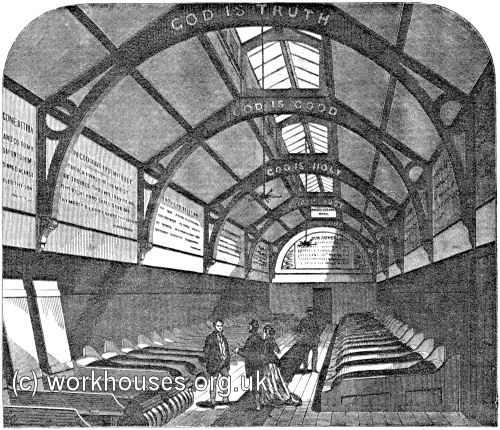

Such reminders could also appear on the walls of the workhouse casual ward where tramps and vagrants spent the night. At St Marylebone workhouse in 1867, scriptural texts, the Lord's Prayer, and the Ten Commandments were printed on the walls and ceiling in red letters on a blue background.

St Marylebone workhouse casual ward, 1867.

© Peter Higginbotham.

A few workhouse did have separate chapel buildings, however. At Bath workhouse, the foundation stone of a new chapel was laid at a ceremony on 10th February 1843 by Tristan Whitter, Esq. M.D., with the workhouse children singing a hymn. The remarkable work of the chapel's builder, a former stone-mason, is commemorated by a plaque on the wall:

To record the services of John Plass, an inmate of the workhouse who, at the age of 78, working with much zeal and industry, laid all the stone of this building. Died 5th June 1849 aged 82, and buried in the adjoining ground.

Bath workhouse chapel, 2000.

© Peter Higginbotham.

In 1924, the Bath workhouse chapel was dedicated to St Martin of Tours who, it is said, cut his military cloak in half, giving one part to comfort a beggar.

A broader concern for the spiritual welfare of workhouse inmates began to surface as early as as 1844. On 23rd February of that year, the Bishop of Exeter, Henry Phillpotts, made a speech on the subject in the House of Lords (Phillpotts, 1844). With particular reference to Poor Law Unions in Devon and Cornwall, he bemoaned the lack of spiritual instruction received by the inmates. This, he asserted, was largely due to the refusal by many Boards of Guardians to offer an adequate salary for a chaplain or even to appoint one at all. By comparison, a chaplain in a prison housing more than a hundred inmates would receive a salary of up to £250, making it viable as a full-time post. Workhouse children in particular suffered from the lack of a chaplain since what religious instruction there was, was usually imparted by the school-master, often himself a pauper and of questionable character. The Bishop also complained that the requirements of the workhouse regulations, for example that "religious consolation" of inmates should only take when requested by the master, were too weak to ensure that the spiritual needs of the inmates were met.

From the late 1850s, less formal religious activities were instigated by the increasing number of laypersons visiting workhouses following the efforts of the Workhouse Visiting Society, founded in 1858 by Louisa Twining. Its aims were "the promotion of the moral and spiritual improvement of Workhouse inmates" — especially "destitute and orphan children", "the sick and afflicted" and "the ignorant and depraved". Visitors undertook a variety of tasks such as holding services in sick wards for those who were unable to attend church services, reading the Bible or other religious works to inmates, and providing pictorial religious materials for those unable to read.

Our Poor: A Bible Reading, Chelsea Workhouse, by James Charles, 1878.

In 1869, the already voluminous record-keeping carried out by the workhouse authorities was added to by the introduction of a new Creed Register which recorded each inmate's admission details together with their religious affiliation. Although this information was already being recorded in other registers, the new Creed Register was intended to be placed at the workhouse lodge and be available for inspection by any person with a legitimate interest. It thus allowed local ministers periodically to monitor for new arrivals who might be in need of their services.

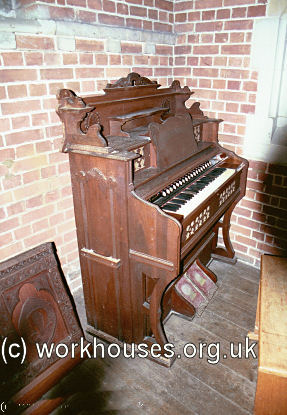

Another outcome of the growing concern for workhouse inmates was an increase in the provision of dedicated chapel buildings. From the 1860s, separate purpose-built chapels were erected on many workhouse sites — often paid for by local charitable efforts. A typical example was the chapel at the Tonbridge workhouse shown below, erected in 1870. As elsewhere in the workhouse, the sexes were segregated and the building had two entrance porches, one for men and one for women.

Tonbridge chapel from the east, 2001.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Tonbridge chapel interior, 2001.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Tonbridge chapel harmonium, 2001.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Later workhouse buildings often incorporated a separate chapel from the outset, such as this one at Nottingham erected in 1903.

Nottingham chapel from the west, 2001.

© Peter Higginbotham

It was not only the workhouse inmates who could learn from the chaplain. A former vicar of Bicester recalled:

Another man there came to me asking me to prepare him for Confirmation. "But," I said, "you have often been at the Holy Communion: haven't you been confirmed?" He said, "yes," but he was a boy when he was confirmed and he did not think seriously about it and now he thought he would like to try it again!

Bibliography

- Cousins, DL (1847) Extracts from the Diary of a Workhouse Chaplain

- Crawfurd, Rev GP (1932) Recollections of Bicester, Oxfordshire 1894 to 1907

- Phillpotts, H (1844) Spiritual Instruction in Union Workhouses (HL Deb 23 February 1844 vol 73 cc107-34)

- Twining, L (1880) Recollections of Workhouse Visiting and Management During Twenty-Five Years

Links

- None.

Unless otherwise indicated, this page () is copyright Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.