Children in the Workhouse

So intoned the Poor Law Handbook of the Poor Law Officers' Journal in 1901 in sentiments that presumably echoed the attitudes of many of those then working in the Poor Law system.

Children featured relatively little in the 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act or in the rules and regulations for its implementation issued by the Poor Law Commissioners. The original scheme of classification of inmates categorized females under 16 as 'girls' and males under 13 as 'boys', with those aged under seven forming a separate class. It probably came as a surprise to the Commissioners that, by 1839, almost half of the workhouse population (42,767 out of 97,510) were children.

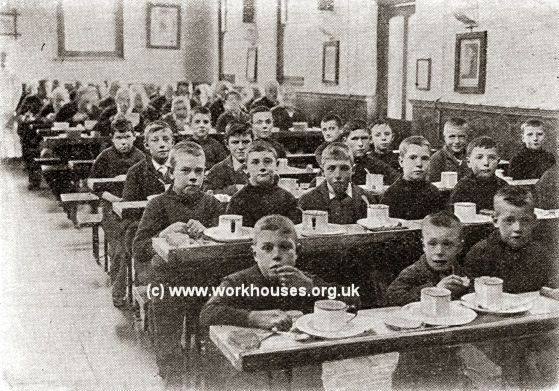

Workhouse Boys, 1909.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Children arrived in the workhouse for a number of reasons. If an able-bodied man was admitted to (or departed from) the workhouse, his whole family had to accompany him. Once inside, the family was split up, with each going to their own section. A child under seven could, if deemed 'expedient', be accommodated with its mother in the female section of the workhouse and even share her bed. She was supposed to have access to the child 'at all reasonable times'. Parents were allowed a daily 'interview' with a child living in the same workhouse, or an 'occasional' interview if the child was in a different workhouse or school. Much of this depended on the discretion of the Guardians — for example, a minimum length of the 'interview' was not laid down.

In 1838, Assistant Commissioner Dr James Phillips Kay noted that children who ended up in the workhouse included 'orphans, or deserted children, or bastards, or children of idiots, or of cripples, or of felons'. Such children were not in the minority: according to the 1909 Royal Commission, around half the children under the care of Boards of Guardians in the nineteenth century were without parents or close relatives. From as early as 1842, the Poor Law Commissioners advised Boards of Guardians that they might detain any orphan child under the age of 16 in receipt of relief if they believed it might suffer injurious consequences by leaving the workhouse. The Poor Law Acts of 1889 and 1899 gave them similar powers in respect of children of parents who were either dead, or "unfit" to control them, for example because they were in prison, convicted of an offence against the child, mentally deficient, in detention under the 1898 Inebriates Act, or permanently disabled and in the workhouse.

Boards of Guardians frequently became the legal guardians of orphaned children until were old enough to enter employment, usually from the age of fourteen. The great majority of girls went into domestic service, while boys usually entered into whatever local employment was on offer or, in some cases, joined the army or navy. Unions had legal responsibility to keep a check on their welfare until they were sixteen, with the union relieving officer visiting them periodically during this period.

The physical conditions in which workhouse children ended up were often appalling. The Poor Law Commissioners' Fourth Annual Report in 1838 recorded a visit by a physician to the Whitechapel workhouse who witnessed:

In another part of the same workhouse, 104 girls slept four or more to a bed in a room 88 feet long, 16½ feet wide and 7 feet high. 89 of the 104 had, perhaps unsurprisingly, recently been attacked with fever.

The Poor Law Commissioners' orders relating to the operation of workhouses contained a single regulation relating to their education:

The education of pauper children came to be provided for in a number of different ways including workhouse schools, separate and district schools, cottage homes, training ships, and the use of local National Schools and Board Schools. Further information on each of these is provided on separate pages.

The use of corporal punishment was one area where strict rules did exist relating to the treatment of children. The regulations issued by the Poor Law Commissioners required that:

- No child under twelve years of age shall be punished by confinement in a dark room or during the night.

- No corporal punishment shall be inflicted on any male child, except by the Schoolmaster or Master.

- No corporal punishment shall be inflicted on any female child.

- No corporal punishment shall be inflicted on any male child, except with a rod or other instrument, such as may have been approved of by the Guardians or the Visiting Committee.

- No corporal punishment shall be inflicted on any male child until two hours shall have elapsed from the commission of the offence for which such punishment is inflicted.

- Whenever any male child is punished by corporal correction, the Master and Schoolmaster shall (if possible) be both present.

- No male child shall be punished by flogging whose age may be reasonably supposed to exceed fourteen years.

As suggested by the last item in the above list, "flogging" could be administered to boys under 14.

Despite these strict regulations, numerous instances of cruelty and abuse of children came to light over the years. Many early instances were extensively reported by The Times which was firmly against the new poor law. For example, the edition of 25th August 1838 carried a long letter from a correspondent in Bath. It catalogued numerous complaints including a claim that he had "known a little boy of eight or nine years to be flogged most cruelly for three days successively, for his complaining to the guardians of his having been unjustly beaten". A study into 21 such Times reports (Roberts, 1963) found that 12 were largely false, 5 were largely correct, and 4 apparently went uninvestigated.

In 1841, GR Wythen Baxter's infamous The Book of the Bastiles — a somewhat lurid compilation of anti-poor-law newspaper reports, court proceedings, correspondence and so on — recorded a news story from the previous year:

Another report related to events at the Kidderminster Union:

In 1847, the five-year old orphan John Rowlands became an inmate of the St Asaph workhouse. In later life, Rowlands became better known as Henry Morton Stanley and tracked down the missing explorer Dr David Livingstone, greeting him with the famous words "Dr Livingstone, I presume?" Stanley's autobiography vividly recalls his memories of St Asaph workhouse which he described as a "house of torture". The scourge of the workhouse was a one-handed schoolmaster called James Francis whose cruelty seemed to know no bounds. Francis appeared to have been implicated in the death of a classmate of Stanley called Willie Roberts. On hearing of Willie's death, Stanley and several other boys sneaked into the workhouse mortuary and discovered his body covered in scores of weals. Stanley finally left the workhouse in 1856 after a violent showdown with Francis.

'Very well, then,' said he, 'the entire class will be flogged, and, if confession is not made, I will proceed with the second, and afterwards with the third. Unbutton.'

He commenced at the foot of the class, and there was the usual yelling, and writhing, and shedding of showers of tears. One or two of David's oaken fibre submitted to the lacerating strokes with a silent squirm or two, and now it was fast approaching my turn; but instead of the old timidity and other symptoms of terror, I felt myself hardening for resistance. He stood before me vindictively glaring, his spectacles intensifying the gleam of his eyes.

'How is this?' he cried savagely. 'Not ready yet? Strip, sir, this minute; I mean to stop this abominable and barefaced lying.'

' I did not lie, sir. I know nothing of it.'

'Silence, sir. Down with your clothes.'

'Never again,' I shouted, marvelling at my own audacity.

The words had scarcely escaped me ere I found myself swung upward into the air by the collar of my jacket, and flung into a nerveless heap on the bench. Then the passionate brute pummelled me in the stomach until I fell backward, gasping for breath. Again I was lifted, and dashed on the bench with a shock that almost broke my spine. What little sense was left in me after these repeated shocks made me aware that I was smitten on the checks, right and left, and that soon nothing would be left of me but a mass of shattered nerves and bruised muscles.

Recovering my breath, finally, from the pounding in the stomach, I aimed a vigorous kick at the cruel Master as he stooped to me, and, by chance, the booted foot smashed his glasses, and almost blinded him with their splinters. Starting backward with the excruciating pain, he contrived to stumble over a bench, and the back of his head struck the stone floor; but, as he was in the act of falling, I had bounded to my feet, and possessed myself of his blackthorn. Armed with this, I rushed at the prostrate form, and struck him at random over his body, until I was called to a sense of what I was doing by the stirless way he received the thrashing.

HM Stanley, 1890

In 1894, a major scandal came to light involving Nurse Gillespie at the Hackney union schools at Brentwood. Gillespie was accused of "systematic cruelty" to the children in her charge including beating them with stinging nettles and forcing them to kneel on wire netting that covered the hot water pipes. Children were also deprived of water and resorted to drinking from the toilet bowls. Her most notorious practice was night-time "basket drill" where children were woken from their sleep and made to walk around the dormitory for an hour with a basket on their heads containing their day clothes, and receiving a beating if they dropped anything. The case came to court at the end of May, 1894 and received wide press coverage.

At a special sitting of the magistrates at the Brentwood Police-court, Ella Gillespie, aged 54, formerly nurse at the Hackney Training Schools, Brentwood, was charged with having on various dates between the months of April and October, 1893, wilfully ill-treated and exposed several children as to cause them unnecessary pain and suffering.

Clara Good, aged 13, deposed that in August last the prisoner knocked her head against the wall because she had been talking to another girl. Two days later witness had to go to the infirmary on account of her head. The prisoner had knocked witness's head against the wall six or seven times prior to August last. In the spring of 1892, whilst witness and two other girls were scrubbing the nursery floor, the prisoner entered and knocked over two scuttles of coal. Then she turned over four pails of water, and rubbed witness's head into the wet coal on the floor. This was because witness bad helped another girl to scrub the corridor, the girl hawing been set to do the work as punishment. Witness saw the prisoner on one occasion strike a girl named Newman with a bunch of keys, cutting her head and making blood Bow. Last July witness saw the prisoner knock down Eliza Clarke (now dead) and her head against the bedstead. This was done because Clarke bad been speaking to another girl. Witness also saw the prisoner dip a boy's bead in a bucket of water on more than one occasion. During the winter prisoner gave the children "basket drill." They were compelled to walk round the dormitory in their night-clothes, in their bare feet, and with a basket on their heads containing their day clothes. The children were kept at basket drill for an hour after being dragged out of bed.

Walter Gibbons, aged seven, stated that the prisoner, bad knocked his head against a wall, and "ducked" his head in a fire bucket. She bad also hit him with a cane. He had done "basket drill" with only his shirt on, and had been caned if he dropped anything.

Elizabeth Chillingworth stated that prisoner had knocked her bead against the wall in 1891. Witness never complained to any one, as she had heard the prisoner threaten to punish the children more if they complained. Witness had seen the children have basket drill from a quarter to 7 till 9 o'clock. Witness once saw the matron enter the ward with a lady and a little boy while the basket drill was going on.

Elizabeth Fawcett, aged 13 years, stated that the prisoner bad slapped her face, pulled her hair, and struck her with a frying pan. The prisoner used to send Alice Payne out for stinging-nettles. She used then to lay the children on the bed and thrash them with the stinging-nettles on their bare backs. Witness had seen the children compelled to kneel on the wire netting that covered the hot-water pipes. Witness saw the prisoner throw a boy named Charles Williams out of bed. The boy's eye was cut against the bedstead, and the prisoner, then sent him to the infirmary to have it strapped up. Witness had had 12 strokes on each hand with the cane when she was an infant, and all the punishment was inflicted at one time.

After other evidence of a similar nature, Sophie Crannis, infant nurse at the schools, and Emily Mason, nursery help, both stated that they bad seen the basket drill going on. Neither had made any complaint about it, but the former had threatened to do so if it was repeated, and the latter came to the conclusion that the authorities must know what was going on, as she was informed by some of the elder girls that it had taken place for years.

Other witnesses reported that Gillespie was regularly drunk and that during 1893, a local brewery had supplied her with 19 four-and-a-half gallon casks of beer. Other staff such as the drillmaster Charles Archer had made excessive use of the cane, both in the number of strokes given, and in not waiting the requisite time after a misdemeanour before its use. It was also revealed that supposedly "surprise" inspection visits by members of the Board of Guardians were invariably preceded by requests from them to be met by a carriage at the local station and to have a good lunch laid on at the school. I was also noted that in the two years prior to 1891, children at the school had never gone outside its walls for recreation. Following the trial, Gillespie was sentenced to five years penal servitude. The Superintendent and Matron were suspended and several other staff resigned.

Hackney Brentwood School, 1908.

© Peter Higginbotham.

In the aftermath of the Brentwood Schools scandal, the operation of the Metropolitan Poor Law Schools was the subject of an official Departmental Committee inquiry chaired by AJ Mundella. The Committee's report, published in 1896, catalogued a large number of shortcomings in "Barrack Schools" as the large separate Poor Law schools were now described by their detractors. The main concrete outcome of the report was the transfer of responsibility, in 1897, to the Metropolitan Asylums Board for all children from certain categories. These were those suffering from contagious diseases of the skin, scalp or eyes; those requiring special treatment or sea air during convalescence; those so physically or mentally defective as to be fit for ordinary school; those ordered by the Industrial Schools Act of 1866 to be taken to a workhouse.

Although such well-publicised cases as the Brentwood Schools were relatively rare, it is in the nature of child abuse, both physical and sexual, that the very large majority goes unreported, through the vulnerable victim's fear of their oppressor, or of the shame they attach to the abuse. It is very likely that the cases that were uncovered were the tip of a very large iceberg.

Workhouse Girls' Dormitory, 1909.

© Peter Higginbotham.

In 1904, in an effort to remove the stigma of having being born in a workhouse, the Registrar General instructed local registrars that birth certificates of such children should carry no indication of this. As a result, such births were then registered with a (sometimes fictitious) street address. For example, births in the Liverpool Workhouse were recorded as having taken place at 144A Brownlow Hill — no such address actually existed.

Bibliography

- Roberts, David (1963) How Cruel Was The Victorian Poor Law? (Historical Journal, 6, 97-107)

Unless otherwise indicated, this page () is copyright Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.