Bolton, Lancashire

Up to 1834

A parliamentary survey published in 1777 recorded Bolton as having a workhouse housing up to sixty inmates. From 1785 (or 1798 according to another source) to 1812, a property on Old Hall Street, later home to the Three Arrows public house, was occupied as a workhouse.

In 1811-12, a new purpose-built workhouse was erected on Fletcher Street, with the paupers at Old Hall Street being transferred to the new premises on 8 May 1812. The governor of the establishment was then John Cartwright. Men were accommodated at the east of the site, women at the west, and children at the south. The 1848 map (below) shows a rectangular block on the Fletcher Street frontage and a large L-shaped block running along Free Street and down parallel with Pilkington Street. The latter appears to consist of a large number of single-room compartments or cottage, rather like back-to-back houses. There are internal staircases and also stairs leading down into the male yard but not into the female yard. This indicates a two-storey structure, with the site sloping downwards from west to east. Whether this block formed part of the workhouse accommodation is unclear.

Fletcher Street workhouse site, 1848.

Fletcher Street workhouse site detail, 1848.

Small workhouses also existed at Little Hulton and Westhoughton, with a larger one at Goose Cote Farm, Turton.

Westhoughton workhouse site, 1849.

Turton workhouse site, 1848.

The Turton workhouse, erected in the 1790s, was strictly run establishment, which operated on the principles of discipline and economy. It provided a refuge for the aged and helpless, and orphan children, and taught trades for those not previously having any. The able-bodied, however, were required to perform hard work, mostly in the form of hand-loom cotton weaving, but with outdoor labour provided for some inmates. Inmates were also given religious and moral education. Those newly admitted to the workhouse were stripped, well washed, and given fresh clothing. Their old clothes, if dirty or infectious, were burned. The workhouse had a large garden and was self-sufficient in vegetables other than potatoes. No beer was allowed to the inmates, but there was plenty of milk. The bread was made from oatmeal, with wheaten bread given only to the sick. The workhouse dietary in around 1832 is shown below.

| BREAKFAST | DINNER | SUPPER | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sunday | Oatmeal pottage, milk and bread. | Butcher's meat boiled with soup, potatoes and other vegetables, with bread. | Oatmeal pottage, milk and bread. |

| Monday | " | Potatoes and butter sauce and bread. | " |

| Tuesday | " | Meat and potatoes boiled together, called hash or lobscouse. | " |

| Wednesday | " | Butcher's meat boiled, same as Sunday. | " |

| Thursday | " | Same as Tuesday. | " |

| Friday | " | Same as Monday. | " |

| Saturday | " | Rice, flour and milk boiled together, and sweetened with sugar and molasses. | " |

Turton offered places in its workhouse on a subscription basis to other townships, of whom 24 participated. In 1832, the workhouse had 76 inmates, with 22 being from Turton, and only eight of those able to work. The remaining 54 inmates were from other townships.

After 1834

Bolton Poor Law Union was formed on 1st February 1837. Its operation was overseen by an elected Board of Guardians, 33 in number, representing its 26 constituent parishes and townships as listed below (figures in brackets indicate numbers of Guardians if more than one):

Lancashire:

Great Bolton (5), Little Bolton (3), Bradshaw, Breightmet, Eaton, Edgworth, Entwistle, Farnworth, Halliwell, Harwood, Horwick, Little Hulton, Middle Hulton, Over Hulton, Kersley, Darcy Lever, Little Lever, Great Lever, Longworth, Lostock, Quarlton, Rumworth, Sharples, Tonge with Haulgh, Turton, West Haughton (2).

Later Additions (all from 1894): Astley Bridge, Belmont, Deane, Smithill.

The population falling within the Union at the 1831 census had been 83,369 with parishes and townships ranging in size from Longworth (population 179) to Great Bolton (28,299).

Like many other unions in the north of England, the Board of Guardians at Bolton decided not to build a new central Union workhouse, but instead carried on using the small workhouses on Fletcher Street and at Turton. Also, flying in the face of the 1834 Poor Law Act, they continued providing out-relief.

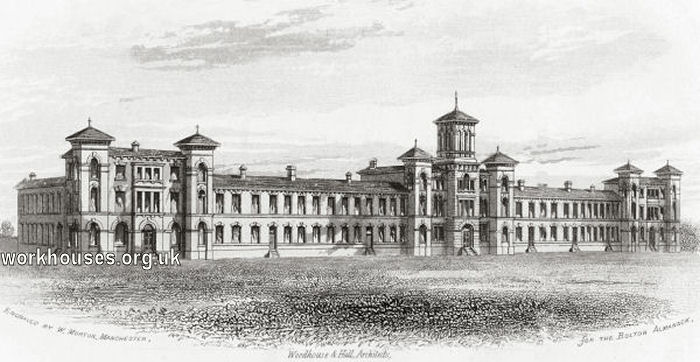

In 1856, following pressure from the Poor Law Board, the Guardians relented and began to negotiate the purchase of a church-owned site at Farnworth known as Fishpool Farm. The deal, for the sum of £2,880, was concluded two years later and the corner stones for the new workhouse was laid on September 8th of that year. Construction of the new buildings, which were to accommodate up to 1,045 inmates, cost around £25,000. The architects were George Woodhouse and Leigh Hall, and the building contractor was Robert Neill. The institution was opened by the then Chairman of the Guardians, Dan Wood Lantham, on 26th September 1861.

Bolton workhouse architects' design, from the east, c.1856.

The layout of the site is shown on the 1893 map below. At that time, railway goods yards still ran along the eastern edge of the site in front of the main entrance.

Bolton workhouse site, 1893.

Built in the then fashionable Italianate style, the main building consists of a three-storey central section, dominated by a 72-foot high tower. To each side are two-storey wings with a three-storeyed pavilion at each end.

Bolton main building from the north, 2000.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The central tower accommodated the administrative offices and also concealed a large water tank at its top. Accommodation for the workhouse Master and Matron was in rooms to the north side of the tower. The northern side of the main building housed male inmates, and females were in the southern side.

Bolton main block entrance from the east, 2000.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The original entrance to the workhouse was via large iron gates set between two square buildings. The one to the left contained the porter's quarters, a probationary ward, and clothing store. The one to the right incorporated the Guardians' board-room and waiting rooms. It was later used as a nurses' home.

Bolton porter's lodge from the north, 2000.

© Peter Higginbotham.

From the rear of the main building emanated a two-storey kitchen block connecting to a single-storey dining-hall.

Bolton dining-hall and kitchen block from the south, 2000.

© Peter Higginbotham.

A fever hospital was erected to the south of the main workhouse in 1872. In 1893, an isolation block was erected to the south of the fever hospital.

Bolton fever hospital, 2000.

© Peter Higginbotham.

In 1894 with the purchase of a further 76 acres of land was purchased at the north of the workhouse, at a cost of £10,000. In 1896, a new infirmary, which became known as Townleys Hospital, was erected there. The buildings comprised a central administration block connecting to a central spine from which two-storey wards pavilions emanated.

Townley Hospital ward block, 2000.

© Peter Higginbotham.

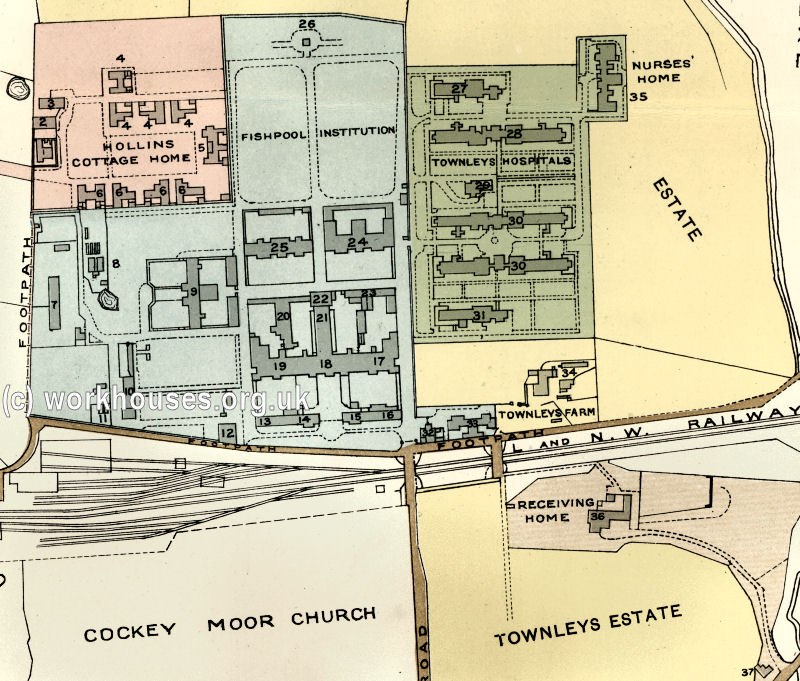

The later site layout is shown on the 1929 map below. By this date, the original workhouse burial ground at the west of the site appears to have been closed.

Bolton workhouse site, 1929.

An anonymised report following an inspection of the premises in around 1908 recorded:

We visited the workhouse and infirmary. The former is a large and rambling mass of buildings, the earlier parts being erected some fifty years back and additions casually added from time to time to meet any special wants. The master, though intelligent seemed inert, and he was in addition very deaf. His deafness was caused by an assault upon him with a knife by an able-bodied pauper.

The whole management was loose and old-fashioned. The Work for the able-bodied was light and not properly supervised, and loafing seemed. to be very prevalent. There has been a very rapid increase of indoor relief in recent years in the Union; so much so that the Local Government Board have recently specially directed the attention of the Guardians to the increase, no doubt largely due to this cause. The Inspector fully admitted the want of systematic control in the establishment, and he proposes to give special attention towards improving the administration.

On the women's side of the workhouse, things were no better. The matron hardly seemed up to the task of managing so large an establishment, and the assistant matron, who had recently been brought from [unnamed institution], was open-mouthed in her condemnation of the administration. She seemed energetic and capable, and although she had effected some improvement she was desirous of leaving the place as soon as she could. She took us into the infirm ward, which was full of bedridden old women, many of whom had been in bed for months. She asserted that they were not properly taken care of, and were dirty and some of them with bed sores.

The laundry was an untidy old-fashioned shed entirely worked by manual pauper labour, under the superintendence of one outside washerwoman.

Until quite recently the pauper women scrubbed and cleaned the men quarters; now the latter clean one floor.

The feeble-minded women do much of this cleaning and scrubbing, and consequently are more in contact with the men than is advisable.

All venereal cases are dealt with by the workhouse medical men and treated in that quarter, to which arrangement the matron of the infirmary strongly objected.

As regards the paupers themselves, the master, matron and assistant matron commented on the poor physique of the paupers, the latter asserting that, so far as women are concerned, it was very inferior to the physique of the [unnamed institution] pauper.

The master and matron both contended that the paupers had greatly deteriorated, especially the men, in the locality during the last twenty years, and that, though they were now more easy to manage, they had not the grit or muscle of their predecessors.

The master considered syphilis as a great contributing factor to pauperism.

Subsequently we visited the infirmary. This was also a huge building — the corridor from the lodge to the nurses' quarters being ¼ of a mile. In its order and management this institution was the antithesis of the other. There are 1,300 beds, 1,100 of which are filled on the average.

The matron, a lady of great capacity and vitality, dominated. the whole establishment. She had 120 nurses under her, and everything seemed to be in excellent order and working smoothly. This is the more noteworthy as a special arrangement is in force, which at first sight would seem calculated to lead to friction and want of uniformity. The infirmary is divided into four sections, each under the control of a consulting doctor, not being on the premises, but who has under him a resident doctor.

There is a steward, who undertakes what he calls the commercial business of the infirmary, and the matron who has entire control of the nursing.

We also visited two receiving homes for children, one for girls and one for boys. All the inmates, except two girls and boys who had just come in, were at school. Both institutions seemed to well fulfil their objects, and the matron of the girls was a woman of very pleasing manners and admirably suited for her work

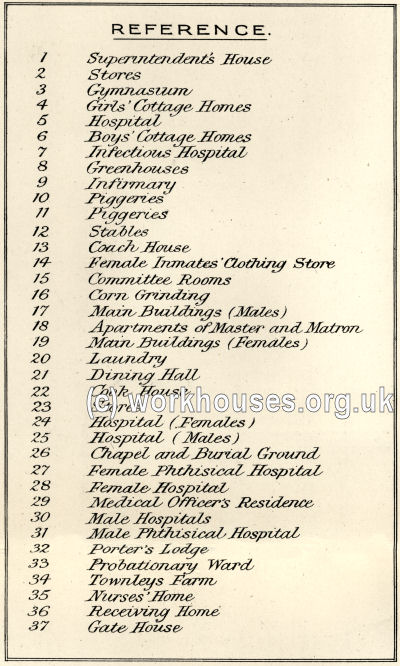

Below is a plan of the workhouse site in 1915, followed by a key to the numbered areas.

Bolton workhouse plan, 1915.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Bolton workhouse plan key, 1915.

© Peter Higginbotham.

By 1915, wounded soldiers were being cared for at Townley's. In May 1917, tents were put up in the grounds to accommodate their increasing numbers.

In 1915 electricity replaced gas for lighting at the site. New extension the following year included maternity and an operating blocks.

From 1919, Townley's Hospital was be managed separately from the workhouse, by then known as Fishpool Institution. A new access route was created so that patients could bypass the workhouse. A total of 150 beds were assigned for use by the town's voluntary hospital, Bolton Royal Infirmary. However, the stigma of the workhouse meant that these often remained empty as many patients would prefer to wait a few weeks for a place at the Infirmary.

In 1930, the Local Government Act abolished the Board of Guardians who had their final meeting on 26th March. The running of the workhouse (now known as Fishpool Institution) passed to a new Public Assistance Committee. In April 1939, Townley's Hospital was 'appropriated' by the council's Public Health Committee for use as a municipal hospital, separate from the Public Assistance Institution.

Following the inauguration of the National Health Service in 1948, Fishpool became Townley's Annexe, and was used for the chronic sick and the elderly, while the fit were moved to homes at Watermillock and Smithills Hall. In 1951, Townley's was renamed to Bolton District General Hospital (Townley's Branch), with Fishpool as its annexe. The site later became the Royal Bolton Hospital. The workhouse buildings were demolished in 2011.

Kings Gate Casual Ward

In 1898, new accommodation for casuals or vagrants, known as Kings Gate Institution, was opened at the west side of Idle Lane (now Central Street), Bolton.

Hollins Cottage Homes

In 1879, Bolton became one of the unions who pioneered the use of "cottage homes" as an alternative form of accommodation for pauper children away from the main workhouse. On an area at the south of the workhouse, four houses were built around a central green, together with a school. Each single-sex cottage accommodated thirty children and had a large living-room, kitchen, three dormitories, and a bedroom for the house-parents.

The site, which became known as Hollins Cottage Homes, was subsequently extended southwards with the erection of further cottages, together with a gymnasium, and superintendent's house at the south-west. The homes were also walled off from the main workhouse site and had their own separate entrance from Plodder Lane at the south.

Bolton cottage homes from the south-west, 2005. The two leftmost homes date from 1878, the next in 1881, and the rightmost in the early 1900s.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Bolton cottage homes superintendent's house with stores and gymnasium behind, 2005.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Bolton cottage homes gymnasium, 2005.

© Peter Higginbotham.

On August 13, 1904, the Bolton Evening News reported that:

The field day and sports day took place on Wednesday in connection with the Bolton Union Cottage Homes, Fishpool Workhouse, on the commodious football and cricket field at the rear of the homes. A racecourse and cricket pitch had been prepared, where a long programme was gone through. The Bradshaw Brass Band headed the procession of children round the cottages on to the field, where each child was provided with a bag of sweets and fruit. Thanks are tendered to the tradesmen and others who contributed to the prize fund and thus helped to add one more bright day to the lot of the hapless ones.

THE CHILDREN OF THE HOLLINS COTTAGE HOMES.

AGAIN! Again! Do it again" It was absolutely irresistible, the baby voice at my feet imploring. demanding rather, that I should once more bounce the ball held up to me in two fat little hands. Their owner sat on the floor, and as I moved to make friends with other babies she punted herself along cleverly with one hand and arm, striving to hold up the ball with the other, always with the cry "Again! again!" She was one of a crowd of happy, mostly chubby and bright little children in the warm, cheerful nursery at Fishpool Institution, from which they pass on at the age of three, if not claimed by them, parents, to one of the Cottage Homes described last week. Two or three. dear little solemn-faced mites not yet; able to walk, or even crawl, were sitting on rugs in froot of the fire at each end of the nursery perfect pictures in their blue or pink frOcks and white pinafores. They were born in the institution, under more or less unfortunate circumstances, but no trace of their sad beginnings was, to be seen in their sweet baby faces, Two of them, especially, were lovely children made to be kissed and petted and made much of by everybody. Up and down the room surged a little sea of restless humanity following their beloved "matron," bubbling over with the latest bits of nursery news, to be told to her by lisping, prattling tongues not yet very good at speech. Me they accepted as a friend because I came with her, patting my bands and welcolming me in winning fashion, and smiling and chuckling in response to notice — except one or two poor little half-starved, dull-eyed, undeveloped children not yet warmed to life in the cheery nursery. Some were learning to walk, one pushing along a wooden horse on , wheels, a great help to his determined effort ,.. Others were staggering shout lon fat little legs still rather unsteady. hugging quaint toys as big nearly as I themselves, and one, a sturdy little fellow with a shod' of fair hair, was engaged in upeetting any who would be upset his chief business in life, said , the Matron, he being " the worst. tempered child we have." But he is a fine likely" little fellow, giving promise of strength and virility that should carry him far when trained and disciplined as it will be, if ho is allowed 1 to remain in the Homes. The same happy homely atmosphere was noticeable in the hospital, where as soon as we appeared a childish voice piped up Turn here!" and would not be stilled until the sister, with a baby in her arms, went to the tot to receive a hug and kiss. In the Cottage where live the little , three to five-year-olds, who do not go to school, another merry crowd showing a healthy joy in life met us with winning ;friendliness, quite sure of our goodwill: I Half-a-dozen chubby little hands were . I pushed into mine all at once, and the children began to tell all sorts of things about themselves and each other, while one proud little dot hustled off to her foster-mother to report that " the lady says my cheeks are rosy." No stiffness or repression here, no forcing of all the ' children into one mould—the little ones are allowed and helped to develop freely and happily along the lines of their own being, and the variety in their outward apparel is significant of a variety of mind and character which is encouraged, as it ought. to he. At the same time there is noticeable as orderli- a charm of behaviour, an absence of roughness and " rowdiness," which makes the children who have been in the Homes long enough to reflect their influence very attractive. While I was there merry voices along the garden paths told that the girls and boys were returning home for dinner. Soon they were seated quietly, hands and faces washed, at. the tables in their own particular cottage. In one I saw how capably the bigger girls take their turn at " waiting on,' carrying the plates from the serving table and depositing them very deftly. Each of the older children had a younger one in charge, seeing that knife and fork and spoon were used properly,. and that the hot-pot and tapi oca pudding were not allowed to soil the tablecloth. Where the " family " is smaller, the fostermother takes her own meal with them, serving at the table—which, of course, is better, tending to more homelike ways. The elder girls learn much by helping to look after the younger ones. They also assist the Matron and fostermothers with the sewing, no little matter with so many to keep well and neatly clad, and with the knitting of the many socks and stockings required. Another healthy and most valuable and educative phase of the life in the Homes is seen in the gymnasium. From the moment when they troop in and. all in a row," change clogs for drill shoes, then run fleetly four by four to set the clogs in a corner out of the way, to the time when, clogs re- assumed, they march out with a ppy " Good-night to instructress and onlookers, the children are full of vivacity and alertness. The least word of individual praise or criticism 'from their teacher spurs them on to renewed effort, and not the richest children in the land are happier or more contented than these, as they exercise and march, skip and dance and swing their clubs, without a thought of care. The contreat between two little girls who have only recently been drafted in from the Probationary Home, and the two biggest, aged about fourteen, show very emphatically what life in the Cottage Homes does for the children. The new arrivals, with hair closecropped during their days of probation as a means towards cleanliness, and a generally ill-fed downcast look, are eloquent of the conditions 'roe , which the Guardians have rescued them. The two hig girls, tall, well set-up, goodlooking girls giving splendid promise, would he a joy and a credit to any parents in the land yet one of the two !came from one of the worst homes in Bolton, her mother 'having been in prison several times. Much more might be told of the life and conditions which are effecting this change and giving the children of misfortune the cbance which every child ought to have, but the last words must he words of praise of the system of aftercare for which, I believe, Bolton is pre-eminent. None of the boys or girls who go out into the world from the Cottage Homes are left to fight the battle of life unaided. Whether they go to work or service, are adopted or hoarded out, and in whatever part of the country, they are put into the care of voluntary visitors, members generally of a local Guild of Help or the GUls' Friendly Society, who befriend and advise them. Every quarter the visitors send a report to the Clerk of the Guardians here. who is most keenly and kindly interested in everything concerning the boys and girls of the Homes, and these reports are kept, so that the history of each is fully known and ready to hand. The visits continue until they are twenty-one, and afterwards by re.. quest, or if it is thought specially desirable. The boys who are learning a trade in Bolton are cared for in the Boys' Home, a house bought by the Guardians in Arkwright-st., which their wages help to support. There they are well looked after, and encouraged to work and save. their shilling ? week pocket money, together with half of all "overtime' pay, being a source of great pride to them. From those who are away, on a training ship, in service, or other place, letters come, telling how they are getting on. or asking perhaps if they may come home for an approaching holiaay---for the cottage where they were brought up so well and happily is still home to them, still regarded with affection and gratitude long after they have passed beyond its bounds into the world of work.

In 2005, the homes were still in use by local social services to provide emergency housing. They have since been demolished to provide additional car parking space for the hospital.

The union also established a Working Boys' Home at Townleys House, a property just across the railway line, at the north-east of the workhouse.

Staff

- 1841 Census - Turton workhouse

- 1851 Census - Turton workhouse

- 1861 Census - Turton workhouse

- 1841 Census - Bolton workhouse

- 1851 Census - Bolton workhouse

- 1861 Census - Bolton workhouse

- 1871 Census - Bolton workhouse

- 1881 Census - Bolton workhouse

- 1891 Census - Bolton workhouse

- Masters and matrons:

- 1861-1875 - Edward and Lavinia Greenhalgh

- 1875-1885 - Mrs and Mrs William Pilling

- 1885-1886 - Mrs and Mrs Ratherham

- 1886- Mrs and Mrs George Davies

Inmates

- Long-term workhouse inmates (1861)

- 1841 Census - Turton workhouse

- 1851 Census - Turton workhouse

- 1861 Census - Turton workhouse

- 1841 Census - Bolton workhouse

- 1851 Census - Bolton workhouse

- 1861 Census - Bolton workhouse

- 1871 Census - Bolton workhouse

- 1881 Census - Bolton workhouse

- 1891 Census - Bolton workhouse

Records

Note: many repositories impose a closure period of up to 100 years for records identifying individuals. Before travelling a long distance, always check that the records you want to consult will be available.

- Bolton Archives and Local Studies Service, Bolton History Centre, Le Mans Crescent, Bolton BL1 1SE. Extensive and unusually complete records survive including: Guardians' minutes (1837-1930); Indoor and outdoor relief registers (1839-1930); Admissions and discharges (1839-1930); Births and deaths (1839-1941); Religious creed registers (1869-1930); etc.

- The Manchester & Lancashire Family History Society has a project to transcribe some of the surviving Bolton workhouse records — more information here. Please note that access to the records is restricted to Society members.

Bibliography

- A Pauper's Palace: A History of Fishpool Institution 1860-1948. by Betty Connor (Neil Richardson, 1989) [Excellent and highly recommended!]

- Leeming, David J (2011) Turton Workhouse.

Links

- None.

Unless otherwise indicated, this page () is copyright Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.