Whitechapel (and Spitalfields), Middlesex, London

Up to 1834

In 1732, An Account of Several Workhouses... reported of St Mary Whitechapel that:

Construction of a new Whitechapel workhouse began in 1768 at the north side of Whitechapel Road though was not finally completed until 1812. In 1776, the building was described as brick-built, 165 feet long, 126 feet 6 inches in depth, and having 30 rooms. It housed a total of 600 inmates, making it one of the largest in the country.

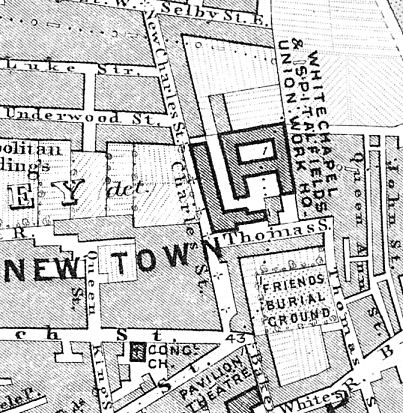

An 1830 map shows the Whitechapel workhouse at the north side of Whitechapel High Street, and the Spitalfields workhouse, to its north on Charles Street.

Whitechapel, 1830.

A workhouse was set up in the parish of Christ Church in Spitalfields as described by an entry in the Account dated September 1731:

THEY have 3 Flesh Dinners in each Week allow'd them, and in other respects their weekly Bill of Fare is much the same as in other Houses.

Christ Church closed its workhouse in 1743 but ten years later obtained a Local Act enabling it to raise money for new premises. In 1754, a lease was taken on a property at the north-east corner of Turnagain Lane (now Vallance Road) and Thomas Street (now Lomas Street), also shown on the above map. After the building was enlarged in 1776, up to 300 inmates could be housed in its thirty-four rooms and were occupied in silk manufacture. In 1832, there were 356 inmates, three-quarters of whom had been employed in the silk trade. The adults were occupied in winding silk and in needlework.

The workhouse of St. Katharine near the Tower was described in the Account as follows:

In 1731, the overseers of the Old Artillery Ground, a Liberty of the Tower of london, hired a house in Gun Street to accommodate the poor. This proved unsatisfactory and in the same year an agreement was maded for the Liberty's poor of the Liberty to be received into the Spitalfields workhouse, the Liberty being too small to erect its own Workhouse. In 1771, when the number of releif claimants had risen sharply, the Liberty decided to hire a building in Rose Lane, Spitalfields, for use as a workhouse. In 1792, the workhouse was transferred to 29 Fort Street, continuing there until 1813, when the poor were farmed out with Mr. Tipple at Hoxton. There they were employed in winding silk, and were provided with a pint of porter on Maundy Thursday. In 1815, after an inspection of the Hoxton establishment proved unsatisfactory, the poor were moved to Stepney

.St Botolph without Aldgate (Middlesex portion) erected a workhouse in 1735 on Nightingale Lane, East Smithfield. In 1776, up to 200 inmates were employed in making wig cauls, winding silk, making slops, picking oakum, and spinning worsted and flax. The building was demolished in 1828 for the construction of St Katherine's Dock.

After 1834

Whitechapel Poor Law Union was formed on 16th February 1837. Its operation was overseen by an elected Board of Guardians, 25 in number, representing its 9 constituent parishes as listed below (figures in brackets indicate numbers of Guardians if more than one):

Middlesex: Christchurch, Spitalfields (6); St Mary Matfelon, Whitechapel (10); Mile End New Town (2); Norton Folgate Liberty; Old Artillery Ground; Tower of London, Old without, and Tower Precinct; St Botolph, Aldgate Without, or East Spitalfield Liberty (2); St Katharine by the Tower; Trinity in the Minories.

The population falling within the union at the 1831 census had been 64,141 with parishes ranging from in size from St Katharine by the Tower (population 72) to St Mary Matfelon, Whitechapel (34,062). The average annual poor-rate expenditure for the period 1834-36 had been £23,036.

For the first few years of its operation, the union carried on using existing parish workhouse accommodation. Conditions in the Whitechapel workhouse apparently left much to be desired — the Poor Law Commissioners' Fourth Annual Report in 1838 recorded a visit by a physician to the premises:

...

I was likewise struck with the pale and unhealthy appearance of a number of children in the Whitechapel workhouse, in a room called the Infant Nursery. These children appear to be from two to three years of age ; they are 23 in number ; they all sleep in one room, and they seldom or never go out of this room, either for air or exercise. Several attempts have been made to send these infants into the country, but a majority of the Board of Guardians has hitherto succeeded in resisting the proposition.

In the Whitechapel workhouse there are two fever-wards; in the lower ward the beds are much too close ; two fever patients are placed in each bed ; the ventilation is most imperfect ; and the room is so close as to be dangerous to all who enter it, as well as most injurious to the sick. In the upper fever-ward the beds are also much too close, but here the beds are single, and the ventilation is better. The privies in this workhouse are in a filthy state, and the place altogether is very imperfectly drained : there is not a single bath in the house.

The Vallance Road (Charles Street/Baker's Row) Workhouse

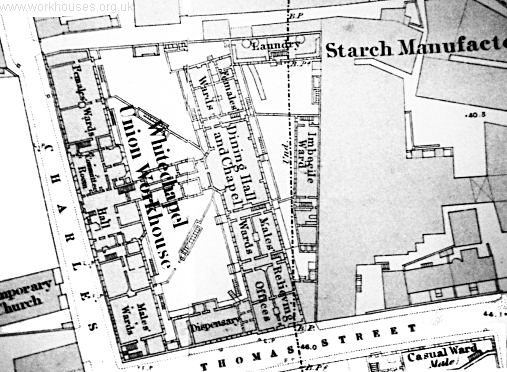

A new Whitechapel and Spitalfields Union workhouse was built in around 1842 on the site of the former Spitalfields parish workhouse at the corner of Charles Street (later Baker's Row, now Vallance Road) and Thomas Street (later Foulbourne Street, now Lomas Street). Its original layout is shown on the map below, published in 1860 though probably dating from a year or two earlier:

Whitechapel (Charles Street) Site, 1860.

A long block ran north-south along Charles Street. A separate large block to its rear had an A-shaped layout.

In 1856-60, a major building scheme was carried out with Thomas Barry as architect. The updated layout is shown on the 1867 map below.

Whitechapel (Charles Street) Site, 1867.

The buildings now had a more conventional H-shaped layout, with females accommodated at the north of the site and males to the south. The block along Charles Street was five storeys high and an entrance hall and committee rooms at the centre, with inmates accommodated to each side. A short two-storey central wing containing offices linked the front block to a parallel six-storey main block at the rear. This housed a chapel cum dining-hall at its centre, with male and female sick wards at each side. A separate laundry was placed on the women's side at the north-east of the site. An imbecile ward ran along the eastern boundary of the workhouse.

In 1860, when the rebuilding of the Charles Street site was complete, the Whitechapel Road workhouse was closed.

In the 1860s, conditions in London workhouses came under scrutiny after the medical journal The Lancet published a series of reports in 1865 revealed the appalling state of many metropolitan workhouse infirmaries. Although Whitechapel was not the subject of a Lancet visit, it was included in a survey of all London's workhouse infirmaries conducted in 1866 by the Poor Law Board. The report found faults with many aspects of the workhouse:

- Ventilation was inadequate and there was a problem with the drains in the male imbeciles' basement.

- There were insufficient nursing staff and the medical officer were overworked and underpaid.

- There was very little furniture in the sick wards other than the beds.

- The beds were inadequate in several respects.

- Only three roller towels a week were provided for a large ward, together with a pound of soap which was also used to wash the furniture. A single comb per ward was provided.

- The general sick had no games although dominoes were provided for the imbeciles.

- A separate ward for sick children should be provided.

- The labour ward should be moved so that screams could not be heard in adjacent wards

A result of the outcry over the poor conditions in London workhouses was the passing in 1867 of the Metropolitan Poor Act. Amongst other things, the Act resulted in a requirement that unions place workhouse infirmaries on separate sites to the main workhouse. In 1872, Whitechapel erected a new workhouse at South Grove, after which the Charles Street site took on the role of union infirmary. In the late 1880s, a number of additions and improvements were made. The imbecile wards were rebuilt. A new dispensary was erected adjacent to the union's relieving offices.

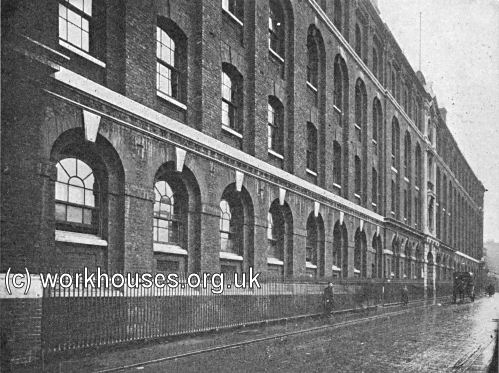

Whitechapel Infirmary from the north, 1902.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Women's ward Whitechapel Infirmary, 1902.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Whitechapel Workhouse, Christmas 1874.

© Peter Higginbotham.

In the autumn of 1888, Whitechapel became the focus of the nation's attention as a result of the activities of "Jack the Ripper". The body of the first of the Ripper's accepted victims, Mary Ann Nichols, was brought to the Whitechapel infirmary's mortuary after its discovery on the morning of 31st August. The mortuary, at that date, was just a shed on Eagle Place, Old Montague Street, several hundred yards from the infirmary. The mortuary attendant, Robert Mann, was himself an inmate of the workhouse. In 2010, the author of the book

Jack the Ripper: Quest for a Killer

claimed that Mann was, in fact, the true identity of Jack the Ripper. One of Ripper's other alleged victims, Martha Tabram (or Tabran) was an inmate of the workhouse casual wards on Thomas Street in the 1881 census.

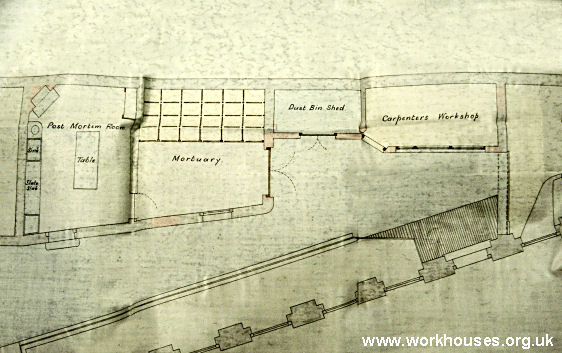

During the inquest into the death of Mary Ann Nichols, complaints were made about the use of an old shed as a mortuary. The following year, a new mortuary was erected at the south-east corner of the workhouse site with an entrance from Thomas Street.

Whitechapel Infirmary mortuary plan, c.1889.

After 1930, the site was taken over by the London County Council. The infirmary became a general hospital known as St Peter's Hospital. It was demolished in the 1960s.

Thomas Street Casual Wards

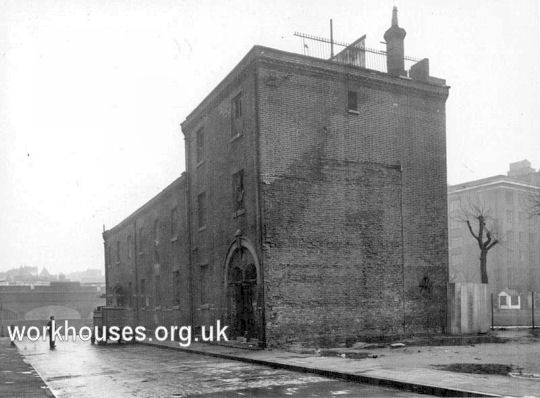

In 1868, the union erected male and female casual wards and oakum-picking roomsclose to the workhouse at 35 Thomas Street (later renamed Fulbourne Street).

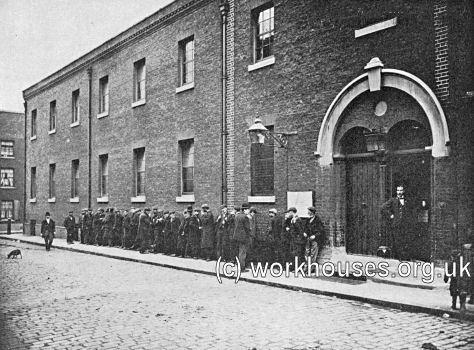

Casuals waiting at entrance to Thomas Street casual ward, 1902.

© Peter Higginbotham.

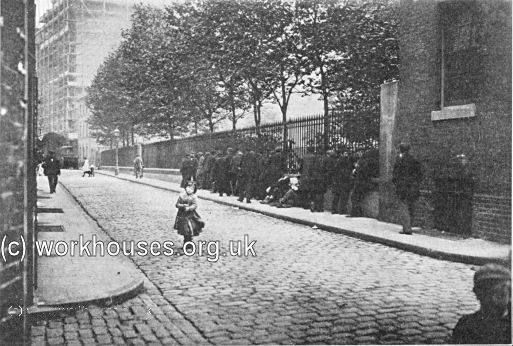

Casuals waiting on Thomas Street, 1902.

© Peter Higginbotham.

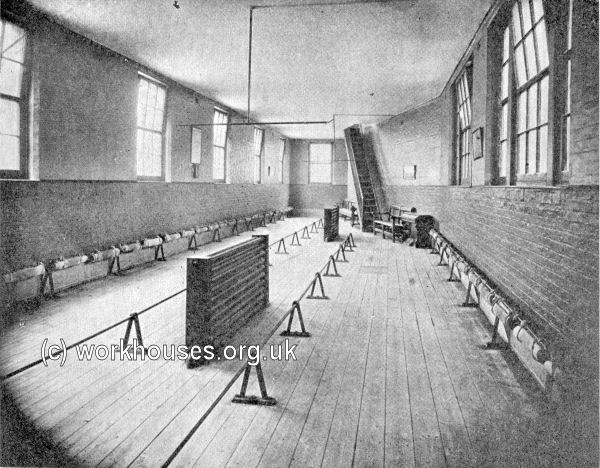

Vagrants or "casuals" were given overnight accommodation in return for a fixed amount of work the following morning. In later years, a two-night stay was required from casuals so that they could not leave without doing the required task of work, and so that they could make an early start after their second night to move on to another workhouse. The casual ward was fitted out with hooks and rails between which low hammocks were slung.

Thomas Street casual ward interior, 1902.

© Peter Higginbotham.

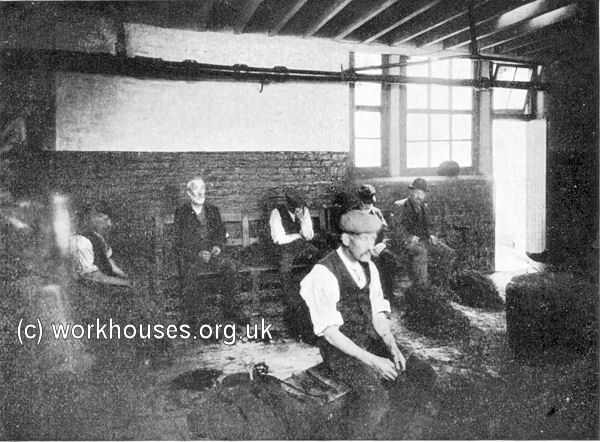

One common form of work was picking oakum — teasing apart the fibres of old ropes.

Men picking oakum at Whitechapel Casual Ward, 1902.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The American writer Jack London visited England in the summer of 1902 and spent time in the East End under cover staying in dosshouses and workhouse casual wards including the one at Whitechapel:

The light was very dim down in the cellar, and before I knew it some other man had thrust a pannikin into my other hand. Then I stumbled on to a still darker room, where were benches and tables and men. The place smelled vilely. The pannikin contained skilly, three-quarters of a pint, a mixture of Indian corn and hot water. The men were dipping their bread into heaps of salt scattered over the dirty tables. The skilly was coarse of texture, unseasoned, gross, and bitter.

By seven o'clock we were called away to bathe and go to bed. We stripped our clothes, wrapping them up in our coats and buckling our belts about them, and deposited them in a heaped rack and on the floor—a beautiful scheme for the spread of vermin. Then, two by two, we entered the bathroom. There were two ordinary tubs, and this I know: the two men preceding had washed in that water, we washed in the same water, and it was not changed for the two men that followed us. This I know; but I am quite certain that the twenty-two of us washed in the same water.

I did no more than make a show of splashing some of this dubious liquid at myself, while I hastily brushed it off with a towel wet from the bodies of other men. My equanimity was not restored by seeing the back of one poor wretch a mass of blood from attacks of vermin and retaliatory scratching.

A shirt was handed me—which I could not help but wonder how many other men had worn; and with a couple of blankets under my arm I trudged off to the sleeping apartment. This was a long, narrow room, traversed by two low iron rails. Between these rails were stretched, not hammocks, but pieces of canvas, six feet long and less than two feet wide. These were the beds, and they were six inches apart and about eight inches above the floor. The chief difficulty was that the head was somewhat higher than the feet, which caused the body constantly to slip down. Being slung to the same rails, when one man moved, no matter how slightly, the rest were set rocking; and whenever I dozed somebody was sure to struggle back to the position from which he had slipped, and arouse me again.

Many hours passed before I won to sleep. It was only seven in the evening, and the voices of children, in shrill outcry, playing in the street, continued till nearly midnight. The smell was frightful and sickening, while my imagination broke loose, and my skin crept and crawled till I was nearly frantic. Grunting, groaning, and snoring arose like the sounds emitted by some sea monster, and several times, afflicted by nightmare, one or another, by his shrieks and yells, aroused the lot of us. Toward morning I was awakened by a rat or some similar animal on my breast.

But morning came, with a six o'clock breakfast of bread and skilly, which I gave away; and we were told off to our various tasks. Some were set to scrubbing and cleaning, others to picking oakum, and eight of us were convoyed across the street to the Whitechapel Infirmary, where we were set at scavenger work. This was the method by which we paid for our skilly and canvas, and I, for one, know that I paid in full many times over.

Though we had most revolting tasks to perform, our allotment was considered the best, and the other men deemed themselves lucky in being chosen to perform it.

`Don't touch it, mate, the nurse sez it's deadly,' warned my working partner, as I held open a sack into which he was emptying a garbage can.

It came from the sick wards, and I told him that I purposed neither to touch it, nor to allow it to touch me. Nevertheless, I had to carry the sack, and other sacks, down five flights of stairs and empty them in a receptacle where the corruption was speedily sprinkled with strong disinfectant.

At eight o'clock we went down into a cellar under the Infirmary, where tea was brought to us, and the hospital scraps. These were heaped high on a huge platter in an indescribable mess—pieces of bread, chunks of grease and fat pork, the burnt skin from the outside of roasted joints, bones, in short, all the leavings from the fingers and mouths of the sick ones suffering from all manner of diseases. Into this mess the men plunged their hands, digging, pawing, turning over, examining, rejecting, and scrambling for. It wasn't pretty. Pigs couldn't have done worse. But the poor devils were hungry, and they ate ravenously of the swill, and when they could eat no more they bundled what was left into their handkerchiefs and thrust it inside their shirts.

The casual ward was in operation until the Second World War. The building was subsequently demolished.

Whitechapel Casual Ward, prior to demolition.

The South Grove Workhouse

The second Whitechapel workhouse was built in 1869-71. It was erected on a long narrow site at the south side of Mile End Road between South Grove (now Southern Grove) and Lincoln Street, and adjacent to the City of London workhouse.

Whitechapel (South Grove) Site, 1894.

In 1873, the new building was pressed into service as a temporary infirmary and school for around 400 children removed from the North Surrey District School at Anerley where the eye condition ophthalmia was a recurrent problem. The "Bow School Infirmary" was in operation for about a year, with South Grove only finally assuming its role as a workhouse on 2nd October 1876.

The buildings, designed by Richard Robert Long, could accommodate over 800 inmates. The entrance block faced onto South Grove, with receiving wards to each side. An entrance archway led through the main courtyard in front of the three-storey administration block which had the workhouse dining hall to its rear, with kitchens attached.

The South Grove workhouse featured in the 1889 novel Captain Lobe by Margaret Harkness who wrote under the pseudonym of "John Law":

The administration block was flanked by two parallel three-storey dormitory blocks, women to the north and men to the south. On their upper floors, these were connected to the central block by escape bridges. The healthy aged were placed on the ground floor, and the infirm on the upper. Along the northern boundary was a smaller three-storey block for healthy aged females. A similar block on the men's side at the south was accompanied by an engineer's shop and the workhouse bakery.

The workhouse was taken over by London County Council in 1930 and the site became South Grove Institution and later Southern Grove House, then Southern Grove Lodge, now closed. In more recent times, part of the premises has been used as a day centre.

South Grove Hospital from the south-west, 2001.

© Peter Higginbotham.

South Grove Hospital from the south-east, 2001.

© Peter Higginbotham.

South Grove Hospital from the north-west, 2002.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Forest Gate School

In 1853-4, Whitechapel Union erected an industrial school for 600 children on a 12-acre site known as Jackass Field at the north side of Forest Lane in Forest Gate. The building was designed by the partnership of Aickin and Capes. It was lit by gas and was fitted with 250 lamps. The site layout in about 1880 is shown on the map below.

Forest Gate District School Site, 1880.

Forest Gate school site entrance from the south, 2002.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Forest Gate school main building from the south-east, 2002.

© Peter Higginbotham.

An infirmary was erected at the west of the main school building.

Forest Gate school infirmary from the south-east, 2002.

© Peter Higginbotham.

In 1869, the school was sold to the newly formed Forest Gate School District, and in 1897 passed to Poplar Union.

Children's Homes, Grays

In 1899, the union erected a group of children's homes at Grays in Essex. The scheme was designed by Christopher M Shiner. Although sometimes referred to as "cottage homes", the homes were placed amongst ordinary houses at different locations around the village and so are better described as purpose-built scattered homes.

Extracts from a 1900 press report on the homes are reproduced below:

The Guardians were compelled to make special provision owing to the dissolution of the Forest Gate School District. This school was originally built by the Whitechapel Board at a time when its hands, so to speak, were full of children. The Jews had not over-run Whitechapel then, and poverty was more acute among the poor families of the district. As the Jews came in the number of children began to diminish, for the new invaders look after their own children through the Jewish Board of Guardians and other voluntary charities. The Poplar Union was admitted into Forest Gate, and in time the Poplar children began to outnumber the Whitechapel children by hundreds. After a good deal of negotiating the Whitechapel Board were allowed to sell out and make the special arrangements of their own which are now in progress.

In most cottage schemes for Poor Law children too many children are admitted into one home. Twenty, and twenty-five, and even thirty, form the average in each of the cottages maintained by certain boards. Of course, where a large number of children have to be accommodated, the cost of providing small cottages would be more than the Guardians dare venture upon. The Whitechapel Guardians having a small number only, are building their cottages for ten children — the smallest Poor Law cottage which the Local Government Board has yet allowed.

With such a comparatively small number in each cottage the Guardians find it easier to secure family life for the children. They propose that each little home shall consist of a mixed family, that is, of children of both sexes and varying ages, under the charge of a foster-mother. Only in one instance is the number to be allowed to exceed ten, and that is in reference to a special cottage which is being put up for the elder boys, who might not be altogether desirable in one of the smaller homes. This cottage will give a home to twenty boys, and, in addition to a foster-mother, it will have a foster-father.

Somewhere in the neighbourhood of the cottages, but not attached to any one of them, will be the headquarters centre. It will consist of an administrative block, of officers' quarters, receiving rooms, and a small infirmary for sick children. The arrangements here are to be as simple arid as free from distinctive and institutional appearance as possible.

A new departure is also to be made in regard to the management of the children. The general control and government of the children in the several cottages are to be left in the hands of a lady superintendent of administrative capacity, who must be a trained nurse.

The headquarters of the homes, Whitehall Lodge, stood on Whitehall Lane and included receiving wards and the Superintendent's block.

Whitehall Lodge.

Up until September, 1914, the superintendent of the homes, based at Whitehall Lodge, was Miss Easton, with Miss E.W. Staff as her assistant.

Whitehall Lodge, 1914. Miss Easton seated centre with her dog. Miss Staff is immediately behind her.

Whitehall Lodge, 1914. Miss Easton (left), Miss Staff (centre left) entertaining Miss Easton's brother and sister-in-law to tea.

Children's houses were erected on Bridge Road (known as Harold Cottages), at the corner of Clarence Road and Park Road (Park Cottages), and on Palmer's Avenue (Dene Cottages). The 1920 map below indicates the location of some of these buildings.

Whitechapel scattered homes site at Grays, 1920.

Harold Cottage, 2010.

© John Webb.

Residents of Harold Cottages, 1914.

Residents of Harold Cottages, 1914.

Park Cottages, 2005.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Inmates and house-mothers of Park Cottages, 1914.

Dene Cottage, the largest of the homes, where the older boys were placed, was the only cottage to be under the charge of a house father and house mother.

Inmates and house-parents of Dene Cottage, 1914.

Advertisement for cottage home parents, 1905.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Mile End Road Receiving Home

By the early 1920, the Whitechapel Union had a children's Receiving Home at 403-409 Mile End Road. In 1924, it could house 42 children. By 1929, the home had been acquired by the Stepney Union and was then referred to as the 'Jewish Homes'. The premises later became known as St Philip's House but the building no longer exists.

Amalgamation with Stepney

On 1 April 1925, the Stepney Union Amalgamation Order resulted in the Hamlet of Mile End Old Town, the Parish of St George In The East, and the Whitechapel Union being added to the Stepney Union which was then renamed the Parish of Stepney Union in 1927.

Staff

- South Grove Workhouse 1881 Census

- Baker's Row Infirmary 1881 Census

- Thomas Street casual Ward 1881 Census

Inmates

- Long-term workhouse inmates (1861)

- South Grove Workhouse 1881 Census

- Baker's Row Infirmary 1881 Census

- Thomas Street Casual Ward 1881 Census

Records

Note: many repositories impose a closure period of up to 100 years for records identifying individuals. Before travelling a long distance, always check that the records you want to consult will be available.

-

The

Ancestry UK

website has two collections of London workhouse records (both name searchable):

- Westminster workhouse records are available on FindMyPast, .

-

London Metropolitan Archives, 40 Northampton Road, London EC1R OHB.

Holdings include: Guardians' minute books (1837-1926); Financial records (1863-1926); Staff records (1857-1925);

- Baker's Row Infirmary — Admissions/discharges (1853-1925); Births (1902-25); Deaths (1877-1916); Creed registers (1915-26);

- South Grove workhouse — Admissions/discharges (1908-1926); Births (1905-26); Deaths (1866-69); Creed registers (1881-1925); etc.

Bibliography

- Higginbotham, Peter Workhouses of London and the South East (2019)

- London, Jack (1903) The People of the Abyss

- Trow, M (2009)

Jack the Ripper: Quest for a Killer

- Webb, John (2011) Grays Cottage Homes (in Panorama, number 49, The Journal of the Thurrock Local History Society).

Links

- None.

Thanks

- Many thanks to John Wood for his contribution to the Grays Homes section of this page.

Unless otherwise indicated, this page () is copyright Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.