Dewsbury, West Riding of Yorkshire

Up to 1834

A parliamentary report of 1777 recorded local workhouses in operation at Batley (for up to 40 inmates), Dewsbury (30), Gomersall (70), Heckmondwike (26), Livesidge [Liversedge] (40), Mirfield (30), and Ossett (80).

Dewsbury's town workhouse was a converted farm at Balk Hill (now the site of a crematorium).

Dewsbury Balk Hill workhouse site, 1855.

Batley had had a workhouse from 1738. A building at the east side of White Lee Road was used for this purpose. A report of 1834 noted that its inmates comprised seven males (aged 79, 76, 68, 55, 54, 52 and 30) and eleven feamles (aged 80, 77, 76, 75, 55, 40, 42, 37, 22, 20, and 8).

Batley workhouse site, 1855.

The Gomersal workhouse was at the top of Flush Lane (now Muffit Lane).

Gomersal workhouse site, 1855.

The building survives as a row of houses.

Gomersal former workhouse, 2006.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The building survives as a row of houses.

The parish of Mirfield appears to have had two workhouses. One was in the vicinity of what is now The Knowl. The other was at the south side of Crossley Lane. Neither building survives.

Mirfield Knowl workhouse site, 1855.

Mirfield Crossley Lane workhouse site, 1855.

In 1927, the District News published a short item on the history of the Mirfield parish workhouse. It recalled that in around 1777, a Workhouse Governor was appointed at salary of £12 12s. a year, subject to three months' notice on either side. In 1801 it was decided to brand the Mirfield paupers clothing with the letters "M.P." (Mirfield Parish) in blue and red cloth. In 1834, John Blackwood was appointed surveyor for the Parish, his duties appearing to include the Governorship of the Workhouse. He received £30 a year salary, and food and accommodation were to be provided for him, his wife, and family. Their duties were "to take care of the paupers and manage the farm belonging to the Parish." At about the same time, it was decided to take one or two more cottages at the Knowl as an addition to the Workhouse, where accommodation was being over-taxed. For combining the appointment of surveyor and Workhouse Governor there was probably the excellent reason that all road repairs was done by the paupers. This was borne out by the following entry from an old document That Benjamin Wilson and George Swithenbank should "stack, fill and break, in a workmanlike manner, 1,500 yards of stone to be laid upon the road leading from Water Royd Lane to Mr. Child's gates, and also the lead of the coals to burn the stone, the whole to be completed at 1s.1d per yard, and to be finished before November 1st. Also that the whole of the paupers shall be employed by them during the time they are engaged on the work."

The Thornhill workhouse stood on what is now Daleside, off Low Road, to the south-west of Thornhill. The site later became known as Workhouse Farm.

Thornhill workhouse site, 1855.

According to Baines' Directory of 1830, Liversedge had a workhouse at Robert Town with John McKinnell as its Governor. A parliamentary report in 1834 recorded 10 inmates in residence — (three males aged 60, 58, and 19) and seven females (aged 50, 40, 28, 14, 14, 5, and 3). The report noted that "aged people and widows prefer a small weekly pittance, and to reside at home with their relatives."

Morley established a poorhouse on Queen Street in about 1730, consisting of two or three one-storey cottages. The site was later occupied by the offices of the Local Board, later the Education Office.

After 1834

Dewsbury Poor Law Union was formed on 10th February 1837. Its operation was overseen by an elected Board of Guardians, 23 in number, representing its 11 constituent parishes as listed below (figures in brackets indicate numbers of Guardians if more than one):

West Riding:

Batley (2), Dewsbury (4), Gomersal (3), Heckmondwike, Liversedge (2), Lower Whitley, Mirfield (3), Morley (2), Ossett (2), Soothill (2), Thornhill.

Later Additions: Birkenshaw (from 1894), Birstall (from 1894), Gawthorpe (from 1890), Ravensthorpe (from 1894).

The population falling within the union at the 1831 census had been 50,232 — with parishes ranging in size from Lower Whitley (population 1,012) to Gomersal (6,189).

Following the creation of the Dewsbury Union, the town saw an upsurge of anti-Poor Law protest. Opposition candidates dominated the Guardians' elections in March 1838, and the new Board resolved not to implement the 1834 Act. The Poor Law Commissioners tried, unsuccessfully, to get the Board's pro-Poor Law vice-chairman Joshua Ingham and other ex officio guardians to carry out the law. An open meeting of the Guardians in August 1838 was halted when the audience became violent, and troops were summoned from Leeds. For the next meeting, 100 Lancers, 76 riflemen, 200 Metropolitan Police, and 600 special constables were present to keep order.

The Guardians continued to oppose the construction of a new union workhouse and carried on using the old township ones at Balk Hill, Gomersal and Batley. It did establish a new Industrial School for orphans in 1849 at Batley.

In 1842, the Poor Law Commissioners investigating the employment and conditions of children in mines and manufactories, discovered that workhouse boys, some as young as eight, were being sent on "apprenticeships" of up to twelve years working in coal mines. As a result, some unions in the coal-mining areas of South Staffordshire and the West Riding of Yorkshire were asked to provide detailed information on the children who had been apprenticed in the mining industry in recent years. The return for the Dewsbury Union is included below.

| Name of Child | Age Yrs.Mos. | Apprenticeship Period. | Premium Paid. | Name of Master. | Residence. | Trade. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1840 | ||||||

| Joseph Gaunt | 11 — | 9 years | None | David Preston | Batley | Coal miner |

| Joseph Scott | 10 — | 11 years | " | James Robertshaw | Liversedge | " |

| John Howden | 11 3 | 9 years, 9 months | " | John Fell | Batley | " |

| William Goodall | 10 — | 10 years | " | William Scaife | Thornhill | " |

| Shallam Lister | 8 — | went on trial and was returned in a few days | " | Valentine Wilkinson | ditto | " |

| Joseph Booth | 10 — | ditto | " | Richard Allatt | Denby | " |

| Thomas Townend | 5 — | went on trial and was returned in 16 days | " | William Bradshaw | Overton | " |

| Edward Robinson | 9 — | went on trial and is not yet bound apprentice | " | Jesse Speight | Flockton | " |

| 1841 | ||||||

| William Firth | 11 — | 10 years | " | John Ledyard | Mirfield | " |

| 1842 | ||||||

| George Booth | 12 — | went on trial and was returned in 3 weeks | " | Henry Chambers | Thornhill | " |

| Wiliiam Grey | 12 — | went on trial and was returned in a few days | " | Joseph Crowther | Morley | " |

| John Fothergill | 10 — | went on trial to | " | John Field | Flockton | " |

| Thomas Whindle | 10 — | went on trial and was returned in a few days | " | Henry Chambers | Thornhill | " |

Five-year-old Thomas Townend was a matter of some embarrassment for the Dewsbury Board of Guardians as he was far too young to be bound as an apprentice. The Guardians claimed that when he had been received from a township workhouse his age had been ascertained by informal enquiry and recorded as seven years. Once the error has been discovered, he had immediately been sent back from the mine. However, the 1842 Royal Commission on Children's Employment in Mines and Manufactories were told that the boy had only been returned to the workhouse after his grandfather and friends had threatened to report the matter to the Poor Law Commissioners.

An 1854 official inspection of Dewsbury's workhouse accommodation found that a number of regulations were being disregarded, for example that married inmates should be separated and that workhouse uniforms should be worn. The same year, it was decided to erect a new union workhouse on Heald's Road at Staincliffe to the north-west of Dewsbury.

The new building was designed by the team of Henry F Lockwood and William Mawson who were also the architects of other Yorkshire workhouses at Bradford, Barnsley, Kingston-upon-Hull, North Bierley and Penistone. Their design for Dewsbury included a range of one and two storey entrance buildings at the east with a central archway, behind which stood the three-storey main building. The main block had the master and matron's accommodation at the centre, with the dining-hall and kitchens to its rear. Male inmates were accommodated in the northern part of the building and females at the south. Separate blocks the north and south of the main building are thought to have been an infirmary and children's industrial school respectively.

In October 1866, the workhouse received an official visit from Poor Law Board Inspector Mr RB Cane. His report painted a somewhat mixed picture of the workhouse's operation:

There are detached schools where the children are separately maintained; they, however, attend in the dining hall at meal times.

There is a detached hospital or infirmary. It contains 46 inmates; they are under the charge of a female nurse (who is rheumatic) assisted by pauper servants.

The medicines are partly given by the nurse, and partly by the pauper. assistants. The Guardians provide the drugs, and they are" dispensed" by the medical officer when he attends at the workhouse. Neither the names of the patients, nor any directions for use are written on or attached to the bottles or pill boxes. Verbal instructions only are given by the medical officer, and the administration of the medicines to the patients for whom they are intended, at the right times, and in the proper quantities, depends upon the recollection of the nurse and her assistants.

There is no "night nursing" (unless the nurse is called up) beyond such as the pauper assistants, if aroused, may be willing to give.

The ventilation might be improved if the skylights were made to open to the external air.

All the waterclosets are defectively constructed, the foul air is drawn into the wards. One of these closets was in a very offensive state.

Many of the beds are too close together.

There is not proper accommodation for the sick who can sit up to take their meals in the wards. The tables are so small that they are obliged to eat their dinners off their knees, and off the forms on which they sit.

I noticed that there were some imbecile women in the wards; although feeble, they were not actually sick. They were sent to these wards to be "taken care of." This is not an unfrequent practice, it is very objectionable for various reasons.

An additional large and commodious "fever hospital," has just been completed, and the services of two additional nurses have been engaged.

At this workhouse there is a "reading room" for the inmates. It is supplied with newspapers, periodicals, &c.;

The fever hospital mentioned in Cane's report may have been the smaller block at the north side of the site. In 1890-94, a large new pavilion-plan infirmary was erected to the south of the workhouse. It had a central administrative block with male and female pavilions to either side. All the new infirmary buildings are lighted by electricity. The layout of the site in 1894 is shown below.

Dewsbury workhouse site, 1894.

Dewsbury new infirmary from the south-east.

© Peter Higginbotham.

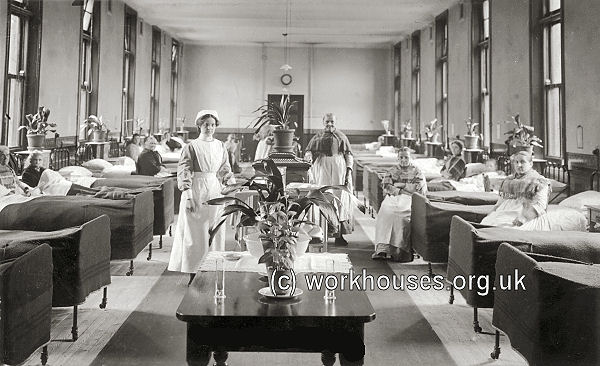

Dewsbury workhouse infirmary ward, early 1900s.

© Peter Higginbotham.

In 1904, the casual wards at Dewsbury received an under-cover visit by Mary Higgs, the Secretary of the Ladies Committee visiting the Oldham Union workhouse. Higgs was interested in vagrancy reform and wished to discover first-hand what conditions were like in workhouse accommodation, particularly for female vagrants. Here are some extracts of her account of her stay at Dewsbury:

Sometime around 1900, a chapel was built immediately to the north of the Heald's Road lodge. In 1907, a third pavilion was added at the south side of the infirmary, running alongside Heald's Road. A nurses' home was erected at the south-west of the infirmary in 1909. In 1912, a new lodge and receiving wards were added at the north-east of the workhouse with a new entrance driveway providing an alternative access route to the site from Halifax Road.

Dewsbury nurses' home from the south-west.

During the First World War, the site was used for accommodating military patients. Three "temporary" hutted ward blocks were erected at the west of the infirmary.

Dewsbury workhouse entrance gate, c.1915.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Dewsbury workhouse entrance gate, c.1915.

© Peter Higginbotham.

In 1923, a new T-shaped men's "mental" block was added on additional land at the north-west of the workhouse, with one of the hutted wards being taken over as for female mental patients. In 1928, a new casual block was erected at the far north of the extended site.

Dewsbury new casual wards, 1930.

After 1930, the institution came under the control of the West Riding County Council which created a new Spen Valley "Guardians' Committee Area". Below are plans of the workhouse and infirmary areas of the site at that date.

Dewsbury workhouse site, 1930.

Dewsbury workhouse site, 1930.

After 1930, the former workhouse was renamed Batley Institution, with the hospital facilities becoming Staincliffe General Hospital. The Institution provided accommodation mainly for the elderly and was renamed Beech Towers in 1950.

Dewsbury workhouse site, 1938.

The former workhouse blocks have now been replaced by modern hospital buildings with only the 1880s infirmary, nurses' home, and casual wards remaining. The site is now known as Dewsbury and District Hospital.

Dewsbury former workhouse site from the south-east, 2009.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Cottage Homes

In 1894, a row of children's cottage homes was erected at the south side of Heald's Road. Initially four houses were erected, later expanded to six. Each accommodated twelve children under the care of a a foster mother. .

Dewsbury cottage homes site, 1930.

A deputation from the Knaresborough Board of Guardians visited the cottages in 1895 and reported:

They are good, plain, two-storied buildings, like well-planned dwellings for artisans. On the ground floor of each is a living room or kitchen, about 10 feet 15, scullery, larder, store-room, linen closet, and lavatory. On the first floor on one side there is a dormitory, 19 feet by 16, with seven beds; a parent's bedroom, and children's bath room in the centre; and a dormitory for five beds the other side. Each home is arranged to accommodate 12 children and the mother. The fittings and furnishings throughout are of the plainest and moat unpretentious character, there being no attempt to bring up the children above their natural station.

The total cost of building the four homes was £3,046 10s. 9d., or £761 12s. 8¼d. each. The cost of furnishing the four was £446 16s. 10d., or £111 14s. 2½. each. In other words each home has actually cost £876 6s. 10¾d. building and furnishing.

The deputation were unable to get the precise cost of the land, as it was part of an immense estate in the hands of the Union.

The provisions are supplied from the workhouse, everything being cooked at the homes but used at the discretion of the mother. As the homes have not been open twelve months yet, it impossible for the Dewsbury authorities under their system to give the exact cost provisions consumed.

It was thought that the cost of clothing would be a little above the average for children in the house. They were not dressed in any distinctive garb.

Each house is managed by one woman, called the mother, who receives from £18 to £25 per annum. All the work of the home is done by the mother and the children, including the washing. The clothes are cut out at the workhouse and made up by the mother and the children. Boys and girls live together until 13 years of age.

The boys and girls scrub the floors, make their own beds, and generally assist in the work of the house, out of school hours.

The children looked happy and healthy, and everything appeared clean and tidy. So far the Dewsbury Guardians are quite satisfied with the experiment.

After 1930, the running of the homes was taken over the local council. Sisters Sylvia and Isabel Green, aged 5 and 3 respectively, entered the cottage homes in the early 1950s. Isabel recalls:

The houses were numbered and segregated by a small wall - the top three were for the girls (known as houses 1, 2 and 3) and the bottom three for the boys (houses 4, 5 and 6). At the back was a large expanse of rough grass area with playing fields, a concert hut, and swings and seesaws etc. Woe betide any girl or boy found talking or playing together on any of these facilities and it wasn't until the late 1950s that were allowed to communicate and then only under strict supervision! There was a ginnell running the length of the grounds at the front of the houses with a Grammar School on the other side and we had to use the bottom gate in term times so that we didn't 'mix'. The smaller top gate was only used for attending the local Methodist Church in Green Lane and for collecting the 'Aunties' shopping. Sometimes we were allowed to attend the local 'flea-pit' cinema in Batley Carr. Parents were allowed to visit the homes on the first Saturday of the month but they had to be there by 2p.m. on the dot or the gates were locked against them.

As well as having a nursery, the institution also had its own cobbler, tailor's shop, pantry/larder supplier, and what seemed to me as a small child at the time to be a huge laundry complete with boiling vats, enormous wringers and steaming presses. Oddly, I loved being sent to 'work' there as I wasn't at all intimidated and it was beautifully clean and warm. Of course, it wouldn't be allowed these days, too much a risk of a clean and flattened small child appearing in the pile of freshly laundered sheets!

All children had to leave the homes at the age of fifteen but we were still under the care of the Council until we were eighteen. While waiting to be fostered out, we would be put to unpaid work under the watchful eye of the 'Master and Matron' of the Home, in the hospital itself, and also in the administration block of Beech Towers. At the end of the day we would cut through the hospital kitchens and the 'cooks' would feel sorry for us and give us big chunks of home made bread spread with jam.

I remember spending time in the nursery before crossing to the Homes and whilst still a small child, I was sent to the isolation block to recover from the German Measles! I was well looked after, in fact the room was warmer than in the 'Houses' as a coal fire was banked up each day.

Unfortunately, it was a small room shared with another patient, an old lady who was in her death throes. Can you imagine the shadows cast by the fire at night time and the sounds of this poor lady 'passing over'? I was well enough to watch the attendants wash and lay out her body, a sight I have never forgotten but, although they didn't consider it necessary to shield me from this sight, I do recall that they were very respectful of her.

The reservoir across from the Low Mills was always stagnant and I don't ever remember passing it, as we cut through the grounds from school, without seeing extremely large dead or dying fish at its edges! I wonder if the Mill used to tip waste there?

The 'Aged' block had small gardens and benches at the front and the men used to garden, sit and smoke pipes, always waving and saying hello as we came through the Gatehouse. It depended on the Gatekeeper, but sometimes in a freezing smoggy winters, we would be allowed to sit at the fire in the Gatehouse and get warm before continuing our journey home.

I remember the vegetable gardens and the small Chapel but not the Tennis courts, just a large field so maybe the court fell into disrepair during the war.

In the drawing of the homes, the small 'squares' represent double-sided toilet blocks and coal-houses. One toilet block and two coal holes per House and you can see the small wall which was the boundary between the girls and boys houses jutting out from the middle one. One thing though, the drawing doesn't show the very large construction of the concert hut which was still standing, although by then in disrepair in the late 1960s.

I was down in the area recently and was surprised and not a little disturbed at how little the area and its buildings had changed, although as you are aware, the 'Homes' no longer stand. I did notice though that at long last, the Methodist Church had repaired its steeple! All through my childhood and even afterwards in the 1960s they were still trying to raise funds to this end, although sadly, the have removed the illuminated clock. My bed used to be against the wall under a window and peering out, that clock was my only means of knowing when to get myself and the little ones up for school, lay the fires, make morning tea for the Aunty in residence etc. Chores we all did at one time or another. I did at one time misread it and got up, did all my chores, went out the back to scrub the 'front' steps before making the Aunty her early morning cuppa, looked up at the clock and it was only 1.am.! Boy was I in trouble for that!

Isabel also recalls Christmas at the homes in 1956 which was to prove particularly memorable:

The rest of the morning passed in a sickening haze as we cleaned the rest of the house, made 12 beds, put the chicken on to cook and prepared the vegetables for dinner, whilst still not being allowed to open presents. About midday, all the children were told to change in to sunday best and sit in a circle on the floor of the sitting room. We were then allowed to open our presents but not play with them. At that point, the Master and Matron ventured in to each house with an assortment of very well dressed ladies and gentlemen, I assume some sort of charitable committee. They would coo over the smallest children and we would be asked questions, usually along the lines of 'Aren't you lucky children? Are you grateful to God for these gifts and the generosity of the Master and Matron?' to which of course we would meekly reply, 'Yes, Miss/Sir' at which point one of them would give us a short lecture about less fortunate children, usually in Africa for some reason before walking on to visit the next house. They usually entered by the main gate so would start in House No.6 and, obviously, finish at the top of the drive in House No.1. A little later, the assistant Master would appear to give the 'all clear' and we would get up off the floor, change out of our Sunday best clothes and put the vegetables on to cook. A miserable meal as the Aunties from each house would then congregate in house no:3 with all the children's gifts and do 'swapsies' to take home for their own families or keep from themselves. To this day I have never eaten a Black Magic chocolate. Mum used to send a box every Christmas along with a rag doll but we never ate a chocolate or played with the dolls. The sweets would be blatantly devoured in front of us after lunch by the adults as the children cleared up and washed the dishes and were then sent out to play in the various yards, no matter the weather. If it was really bad, they would open up the concert hall and we would run about in there. I can still remember the backdrop on the stage and the concerts we children would be obliged to put on for visitors in the early days, but that's another story.

Later in the evening, we would put on our coats and wait for a member of the Green Lane Methodist Church, usually sent along up the snicket and through the small top gate, to collect us if needed to boost the congregation and choir. Twice in the 1950s we were shook from sleep and told to perform this duty as a local radio station was there recording the sermon.

The Victorian values of the Workhouse still existed well into the 1950s, even the early 1960s, but none of this has ever put me off the spirit of Christmas. In later years, with a change of staff, the celebration became a little more enjoyable. We were allowed to open and keep one or two of our gifts, apart from the chocolates, and a television set arrived in House No.3 around which all the children from the different houses would congregate from time to time, kindling my long standing love of Coronation Street!

Looking back at the design of the individual houses, I can remember the total layout of each one, they were incredibly solidly built each with its own bathroom, separate washroom containing six basins, two indoor lavatories and an outdoor toilet, comfortable facilities a lot of families at that time could only wish for. Yet it was always freezing cold, the fires in the two children's bedrooms remaining unlit unless the doctor was on his way to visit a sick child. The only fires allowed were in the Aunty's room and the 'house'. A concert hall, small football pitch and swings, see-saws, roundabouts etc were also provided, comfort and care built very much on the enlightened Quaker tradition, but in my opinion the demolition of these buildings brought to a close a miserable era and heralded in a much more enlightened approach to unfortunate children. It's people that make a home.

Staff

- 1847 — Dewsbury Workhouse Governor: Jno. Blackwood; Batley workhouse Matron: Rachel Lee; Gomersal workhouse Governor: Jno. Seamour.

- 1881 Census

Inmates

Records

Note: many repositories impose a closure period of up to 100 years for records identifying individuals. Before travelling a long distance, always check that the records you want to consult will be available.

- West Yorkshire Archive Service (Kirklees Office), Central Library, Princess Alexandra Walk, Huddersfield HD1 2SU. Very few local records survive — holdings include: Guardians' minute books (1837-42).

Bibliography

- Dewsbury Workhouse by Anthony Chadwick (Ripon Museum Trust leaflet, 1996)

- Higgs, Mary (1904) A Tramp Among Tramps.

- Knott, J (1986) Popular Opposition to the 1834 Poor Law. Croom Helm.

- White, W. (1847) Directory and Topography of Leeds, Bradford, Halifax, Huddersfield, Wakefield, and the whole of the clothing districts of the West Riding of Yorkshire

Links

- Ripon Workhouse Museum and Garden, Sharow View, Allhallowgate, Ripon HG4 1LE.

Unless otherwise indicated, this page () is copyright Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.