The Old Poor Law

Origins of the Old Poor Law

The origins of parochial poor relief extend back at least as far as the fifteenth century. With the decline of the monasteries, and their dissolution in 1536, together with the breakdown of the medieval social structure, charity for the poor gradually moved from its traditional voluntary framework to become a compulsory tax administered at the parish level.

Legislation prior to this point largely dealt with beggars and vagabonds. In the aftermath of the Black Death (1348-9) labour was in short supply and wages rose steeply. To try and keep this in check, several Acts were passed aimed at forcing all able-bodied men to work and keep wages at their old levels. These measures led to labourers roaming around the country looking for an area where the wages were high and where the labour laws not too strictly enforced. Some took to begging under the pretence of being ill or crippled. In 1349, the Ordinance of Labourers (36 Edw.III c.8) prohibited private individuals from giving relief to able-bodied beggars.

In 1388, the Statute of Cambridge (12 Rich.II c.7) introduced regulations restricting the movements of all labourers and beggars. Each county "Hundred" became responsible for relieving its own "impotent poor" — those who, because of age or infirmity, were incapable of work. Servants wishing to move out of their own Hundred needed a letter of authority from the "good man of the Hundred" — the local Justice of the Peace — or risked being put in the stocks. Following this Act, beggars could pretend neither to be labourers (who needed permission to wander), nor to be invalids (who were also forbidden to wander). The 1388 Act is often regarded as the first English poor law. However, lack of enforcement limited its impact and effect.

Further legislation followed over the next two centuries. In 1494, the Vagabonds and Beggars Act (11 Henry VII c.2) determined that: "Vagabonds, idle and suspected persons shall be set in the stocks for three days and three nights and have none other sustenance but bread and water and then shall be put out of Town. Every beggar suitable to work shall resort to the Hundred where he last dwelled, is best known, or was born and there remain upon the pain aforesaid." Worse was to come — the 1547 Statute of Legal Settlement (1 Edw. VI. c.3) enacted that a sturdy beggar could be branded or made a slave for two years (or for life if he absconded). The Act condemned "...foolish pity and mercy" for vagrants. On a more positive note, cottages were to be erected for the impotent poor, and they were to be relieved or cured.

The seeds of the future direction of the poor laws in a short-lived Act of 1536 which required Churchwardens in each parish to collect voluntary alms in a 'common box' to provide handouts for those who could not work. At the same time, the idle and the able-bodied poor were obliged to perform labour, with punishment for those who refused. The Act also placed a prohibition on begging and on unofficial almsgiving. In the following decades, compulsory poor-taxes were established in London, Cambridge, Colchester, Ipswich, Norwich, and York. This principle was adopted nationally in 1572 with the introduction of a local property tax, the poor rate, which was assessed by local Justices of the Peace and administered by parish overseers. The money raised was to be used to relieve 'aged, poor, impotent, and decayed persons'.

An Act of 1564 aimed to suppress the 'roaming beggar' by empowering parish officers to 'appoint meet and convenient places for the habitations and abidings' of such classes — one of the first references to what was subsequently to evolve into the workhouse. This was followed in 1576 by an Act For Setting the Poor on Work which provided that stocks of materials such as wool, hemp, and flax should be provided and premises hired in which to employ the able-bodied poor.

In 1597, an Act For the Relief of the Poor (39 Eliz. c.3) required every parish to appoint Overseers of the Poor whose responsibility it was to find work for the unemployed and to set up parish-houses for those incapable of supporting themselves.

The 1601 Poor Relief Act

1601, the 43rd year of the reign of Elizabeth I, saw the passing of An Acte for the Reliefe of the Poore (43 Eliz. I c.2) which, although it was essentially a refinement of the 1597 Act, is often cited as marking the foundation of the Old Poor Laws.

Opening section of the 1601 Act.

Under the 1601 Act, each parish was obliged to relieve the aged and the helpless, to bring up unprotected children in habits of industry, and to provide work for those capable of it but who were lacking their usual trade.

The main objectives of the 1601 Act were:

- The establishment of the parish as the administrative unit responsible for poor relief, with churchwardens or parish overseers collecting poor-rates and allocating relief.

- The provision of materials such as flax, hemp and wool to provide work for the able-bodied poor. Any able-bodied pauper who refused to work was liable to be placed in a 'House of Correction' or prison.

- The relief of the 'impotent' poor — the old, the blind, the lame, and so on. This could include the provision of 'houses of dwelling' — almshouses or poorhouses rather than workhouses. The Act also made the relief and maintenance of such persons, the legal responsibility of their parents, grandparents, or children, if such relatives were themselves able to provide such support.

- The setting to work and apprenticeship of children

Collection of the poor rates was done by the parish overseers who were unpaid and elected annually by the parish vestry. This was never a popular job and even missing one of their regular monthly meetings could result in an overseer receiving a hefty one pound fine. The poor-rates were dispensed to the needy of the parish as 'out-relief', usually in the form of bread, clothing, fuel, the payment of rent, or money.

You can read the full text of the 1601 Act.

The Poor Rate

The 1601 Act empowered parish overseers to raise money for poor relief from the inhabitants of the parish, according to their ability to pay. The poor-rate was originally a form of local income tax, but over time evolved into the rating system — a property tax based on the value of real estate. In general, the poor-rate was paid by the tenant of a property rather than its owner. Each parishioner's property and payment would be recorded in the Overseers' accounts books.

Example of an Overseer's poor rates accounts book from Wakefield, 1770.

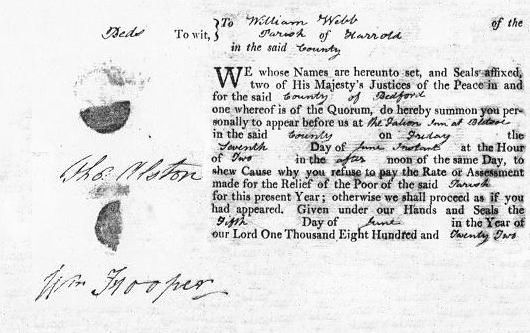

Failure to pay the poor-rate would result in a summons to appear before a Justices of the Peace who could impose a fine or the seizure of property, or even prison.

Example of a poor rate summons from 1822.

The poor rates funded payments to the needy poor in the parish, in cash or to pay for items such as those highlighted in the example below: handkerchief, a shirt, shift, shoes, a coffin, a kettle, or in sickness. Such handouts were known as out-relief.

Example of out-relief payments at Lyme Regis in 1796.

The Settlement Act

In 1662, another highly significant piece of legislation An Act for the better Relief of the Poor of this Kingdom (13&14 Car. II c.12) — otherwise known as the Settlement Act — was passed. In fact, the principle behind this Act was not really new and had its origins in the 1388 Statute of Cambridge. The new Settlement Act allowed for the removal from a parish, back to their place of settlement, of newcomers whom local justices deemed "likely to be chargeable" to the parish poor rates. Exemption was given if the new arrival was able to rent a property for at least £10 a year, but this was well beyond the means of an average labourer.

The 1662 Act did not specify how a person's settlement was defined — the basic principles were already long established. A child's settlement at birth was taken to be the same as that of its father. At marriage, a woman took on the same settlement as her husband. Illegitimate children were granted settlement in the place they were born — this often led parish overseers to try and get rid of an unmarried pregnant woman before the child was born, for example by her transporting to another parish just before the birth, or by paying a man from another parish to marry her.

A further Act in 1691 (3 William & Mary c.11) specified aditional ways in which settlement could be acquired. If a boy was apprenticed, which could happen from the age of seven, his parish of settlement became the place of his apprenticeship. Another means of qualifying for settlement in a new parish was by being in continuous employment for at least a year. To prevent this, hirings were often for a period of 364 days rather than a full year, or with a small amount of unpaid holidy included. Conversely, labourers might quit their jobs before a year was up in order to avoid being effectively trapped in a disagreeable parish.

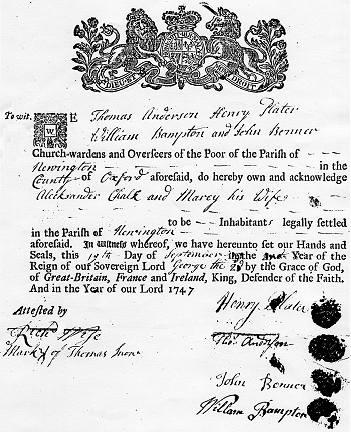

Example of a settlement paper from 1747.

You can read the full text of the 1662 Settlement Act. Interestingly, the Act was the first ever to mention the term "workhouses".

In 1697, an Act For supplying some Defects in the Laws for the Relief of the Poor (8&9 Will II c.30) gave newcomers with certificates from their own parish protection until they actually became chargeable on the poor rate. A century later, in 1795, An Act to prevent the Removal of Poor Persons until they shall actually become chargeable (35 Geo. III c. 101) extended this protection to all except pregnant unmarried women. Parishes made these the least welcome because they were considered the most expensive to support.

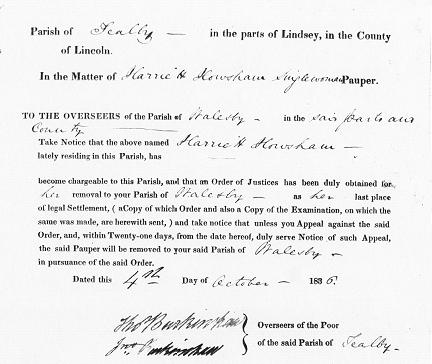

Example of a removal notice from 1836.

Badging the Poor

The 1697 Act also required the "badging of the poor" — those in receipt of poor relief were required to wear, in red or blue cloth on their right shoulder, the letter "P" preceded by the initial letter of their parish. Badging was taken up by some parishes and not by others, and the procedure was eventually discontinued in an Act of 1810 (50 Geo. III c.10).

Pauper's badge for Ampthill parish

The operation of the Settlement Act, and its subsequent amendments, proved complex, confusing and contentious. Expensive legal battles often took place between a parish attempting to remove a pauper whom it claimed it had no duty to support, and the parish that it claimed did have responsibility. For example, early in 1837 a man called William Withers was travelling from Bristol to London when he became stricken with severe rheumatism and had to spend six weeks in the parish workhouse at Walcot in Bath. Eventually, Walcot decided to remove him to Clerkenwell and at 6pm he was put aboard the outside of a coach open to the wind and snow. After seven hours, at the halfway point at Newbury, he had to be lifted off the coach and revived with a little brandy and water. When he arrived in Clerkenwell, he had lost virtually all use of his hands and feet and was a bedridden invalid. A court then decided that, due to a technicality, his removal from Walcot had been illegal. However, to rectify matters, he would have to return there for removal proceedings to be reconducted. In the meantime, Clerkenwell could pass on the cost of Withers' upkeep to Walcot, and so treated him like a king, to the tune of five shillings a week. The ratepayers of Walcot had had to stump up £500 in legal costs plus the initial removal expenses and the cost of his keep until he was fit to return to Bath whereupon he could be removed again — legally — back to London.

Although various amendments continued to be made to the settlement and removal laws, notably an 1846 statute (9&10 Vic. c.66) which granted settlement after five years' residence, and the 1865 Union Chargeability Act (28&29 Vic. c.79) when all settlement powers were placed in the hands of the Poor Law Union and its Board of Guardians, the law was not finally abolished until 1948.

Bastardy

Between 1732 and 1744 a number of changes took place in how the law treated the responsibility for illegitimate children:

- In 1732-3, a woman pregnant with a bastard was required to declare the fact and to name the father.

- In 1733, the putative father became responsible for maintaining his illegitimate child; failing to do so could result in gaol. The parish would then support the mother and child, until the father agreed to do so, whereupon he would reimburse the parish — although this rarely happened.

- In 1743-4, a bastard born to a women convicted of vagrancy was to have the settlement of its mother, regardless of where the child was actually born. The mother was to be publicly whipped.

Knatchbull's Act (The Workhouse Test Act)

Sir Edward Knatchbull's Act of 1722-3 — For Amending the Laws relating to the Settlement, Imployment and Relief of the Poor (9 Geo. I c.7) enabled workhouses to be set up by parishes either singly, or in combination with neighbouring parishes.

An abstract of Knatchbull's Act is given below:

|

The Church-Wardens and Overseers of the Poor of any Parish, with the Consent of the Major Part of the Parishioners, in Vestry, or other Publick Meeting for that purpose assembled, upon usual notice given, may purchase or hire any House or Houses in the Parish or Place, and Contract with Persons for the Lodging, Keeping and Employing of poor Persons; and there they are to keep them, and take the Benefit of their Work and Labour, for the better Maintenance and Relief of such Persons. And in case any poor Person shall refuse to be Lodg'd, Kept and Maintain'd in such House or Houses, such Person shall be put out of the Parish Books, and not entituled to Relief. Where Parishes are small, two or more such Parishes, with the Approbation of a Justice of the Peace, may unite in Purchasing or Hiring Houses for the Purposes aforesaid. And Church-Wardens, etc. of one Parish, with the Consent of the Major Part of the Parishioners, may contract with the Church-Wardens, etc. of any other Parish, for the Lodging and Maintenance of the Poor. But no poor Persons, or their Apprentices, Children, etc. shall receive a settlement in the Parish, Town, or Place to which they shall be removed, by Virtue of this Act. Note. This is a General Law, and extends to all England. |

You can read the full text of the Knatchbull's Act

The Workhouse Test

Knatchbull's Act was also the first legal embodiment of the workhouse test — that the prospect of workhouse should act as a deterrent and that relief should only be available to those who were desperate enough to accept its regime. The workhouse test probably owes its origin to Matthew Marryott, a workhouse manager from Buckinghamshire, who opened his first establishment at Olney in 1714. Marryott promoted the operation of many workhouses in the south of England. He may also have had a hand in the writing of the 1725 publication An Account of Several Workhouses for Employing and Maintaining the Poor, which described the operation of over 100 workhouses and the financial benefits to a parish of their introduction.

Parishes often adopted Knatchbull's Act in the belief that it would reduce the demand for poor relief, and thus the parish poor rates, especially if the workhouse was the only form of relief on offer. Parishes could also operate a mixed system, with 'deserving' claimants such as the elderly or chronic sick being given out-relief (hand-outs in cash or kind), while support for claimants such as the able-bodied could be limited to the workhouse.

By 1732, following Knatchbull's Act, it is estimated (Slack, 1990) that about 700 workhouses were in operation. Parliamentary reports in 1776-7 list a total of almost 2,000 parish workhouses in operation in England and Wales — approximately one parish in seven. However, the great majority of parishes did not establish a workhouse, preferring to relieve their poor only through out-relief.

Farming the Poor

Following Knatchbull's, the actual running of workhouses was not necessarily undertaken by the parish itself. It could instead be contracted out to a third party who would undertake to feed and house the poor, charging the parish a weekly rate for each inmate. The contractor would also provide the inmates with work and could keep any income generated. This system was known as 'farming' the poor. The contract was usually awarded to the bidder offering the best price for the job which might take a variety of forms, for example maintaining all the paupers in a parish, or just managing the workhouse, or just a particular group of paupers such as infants and children, or lunatics, or providing medical relief.

Eden, in his 1797 survey of the poor in England, described the operation of "farming" in the Farnham workhouse:

The contractor is allowed the use of the house and furniture, and the earnings of the Poor, and receives £1,000 a year for which he is bound to maintain the Poor of every description, but not bear the expense of removals, appeals, or other law contests. There are at present (Oct., 1795) 124 inmates, of whom 50 are old and infirm, and generally about the same in winter. There are a few out-pensioners, but the payments are very trifling, as it is more for the interest of the contractor to offer the Poor who apply for relief no alternative but the house. The infirm who can work are employed in picking wool, the children attend the carding machine, spin, etc., and are taught to read twice a day. Boys and girls, men and women sleep in different quarters of the house. The contractor says he keeps no account of expenses or earnings.

Gilbert's Act

Thomas Gilbert's Act — For the Better Relief and Employment of the Poor (22 Geo. III c.83) was passed in 1782. It aimed to organize poor relief on a county basis with each county being divided into large districts corresponding to a Hundred (an old administrative unit within a county) or other large group of parishes. Such unions of parishes could set up a common workhouse although this was to be for the benefit only of the old, the sick and infirm, and orphan children. Perhaps most significantly, able-bodied paupers were not to be admitted but found employment near their own homes, with land-owners, farmers and other employers receiving allowances from the poor rates to bring wages up to subsistence levels.

Gilbert's Act also introduced significant changes in the administration of poor relief. Gilbert Unions were controlled by a board of Guardians, one from each member parish, elected by ratepayers and appointed by local magistrates. This represented a major shift in power from the parish to the landed gentry. The Guardians' work was to be supervised by a Visitor, also appointed by magistrates. The Act also provided model rules for the running of a workhouse.

Although groups of parishes — notably in East Anglia — had formed Local Act incorporations prior to Gilbert's Act, it made the formation of such unions much simpler and cheaper to undertake. However, Gilbert's scheme never took off in a big way and less than a hundred Gilbert's Unions were ever formed.

You can read the full text of Gilbert's Act

Sir William Young's Amendment Act

In 1795, Sir William Young introduced An Act to Amend so much of an Act... as prevents the distributing occasional relief to poor persons in their own houses, under certain circumstances and in certain cases. (36 Geo. III c.23). This Act repealed some of the provisions of Knatchbull's Act and gave greater powers to local magistrates to order outdoor relief. This was not a universally popular measure and may have encouraged some parishes to form Gilbert's Unions which were exempt from such measures.

Bentham's Scheme

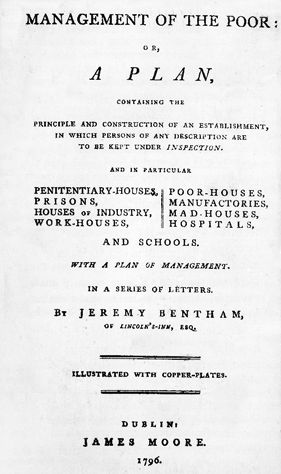

In 1796, Jeremy Bentham, the great legal reformer and utilitarian philosopher, published a grandiose scheme for 'Pauper Management'. This early example of privatisation proposed the formation of a National Charity company that would construct a chain of 250 enormous workhouses, financed by a large number of small investors. Each workhouse would hold around two thousand inmates who would be put to profitable work and fed on a spartan diet.

The Speenhamland System

Although it had its origins in the 1782 Act, the growing practice around this time of supplementing low wages from the poor rate became known as the Speenhamland system, named after the Berkshire parish of that name. It was here, in 1795, that magistrates decided to supplement wages on a scale that varied with price of bread and number of children:

When the gallon loaf shall cost 1s.4d., then every poor and industrious man shall 3s. weekly for his own, and 1s.10d. for the support of every other of his family.

And so in proportion as the price of bread rises or falls (that is to say) 3d. to the man and 1d. to every other of the family on every penny which the loaf rises above a shilling.

Thus, if the price of bread rose to 1s.3d., a married man with two children would be guaranteed a wage of 3s.9d for himself plus three times 1s.9d., giving a total of 9 shillings a week.

Although never sanctioned by formal legislation, this practice, in various forms, became widespread. However, it was held in some quarters that the system led to able-bodied labourers believing that they were entitled to parish relief when out of work, and lacking industry and respect for their employer when in work.

Sturges Bourne's Acts

In an effort to improve the administration of poor-relief (and reduce costs) the Sturges Bourne Acts: The 1818 Act for the Regulation of Parish Vestries (58 Geo. III c. 3) and the 1819 Act To Amend the laws for the Relief of the Poor (59 Geo. III c. 12). These acts allowed parishes to appoint small committees, or Select Vestries, to scrutinise relief-giving. Election to Select Vestries was by parish ratepayers given votes (up to six) in proportion to the value of their property. In addition, a rate could be raised specifically to build or enlarge a workhouse. To help the parish overseer (a unpaid post) with the growing administrative burden imposed by poor relief, a salaried assistant overseer could also be appointed.

However, by the late 1820s, there was growing dissatisfaction with the whole system, particularly from the well represented land-owning classes who bore the brunt of the growing poor-rate burden. There was also growing unrest amongst the poor, particularly in rural areas, which even lead to rioting and the attacking of poorhouses, notably from those who identified themselves as supporters of the shadowy figure of Captain Swing. In 1832 the British Government decided to appoint a Royal Commission to review the whole poor relief system.

The 1832 Royal Commission

The Royal Commission, under the chairmanship of the Bishop of London, conducted a detailed survey of the state of poor law administration and prepared a report. This was largely the work of two of the Commissioners, Nassau Senior and Edwin Chadwick. The report took the view that poverty was essentially caused the indigence of individuals rather than economic and social conditions. Thus, the pauper claimed relief regardless of his merits: large families got most, which encouraged improvident marriages; women claimed relief for bastards, which encouraged immorality; labourers had no incentive to work; employers kept wages artificially low as workers subsidized from the poor rate.

The Royal Commission published its report in March, 1834, and made a series of 22 recommendations which were to form the basis of the new legislation that followed in the same year. Its main legislative proposal was that:

In addition, it recommended:

- The grouping of parishes for the purposes of operating a workhouse

- That workhouse conditions should be 'less eligible' (less desirable) than those of an independent labourer of the lowest class

- The appointment of a central body to administer the new system

The report also revived the workhouse test — the belief that the deserving and the undeserving poor could be distinguished by a simple test: anyone prepared to accept relief in the repellent workhouse must be lacking the moral determination to survive outside it.

The subsequent 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act led to a major overhaul of how poor rleief was administered. The Act and its later revisions became known as the New Poor Law.

Bibliography

- Slack, Paul. The English Poor Law, 1531-1782, 1990, CUP.

- Webb, Sidney and Beatrice English Poor Law History, 1927, Longmans, Green & Co., London.

- Webb, Sidney and Beatrice English Poor Law Policy, 1910, Longmans, Green & Co., London.

Unless otherwise indicated, this page () is copyright Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.