Greenock, Renfrewshire

The Captain Street Poorhouse

From around 1850, the parish of Greenock operated a poorhouse in a building at the north side of Wellington Street, between Duncan Street and Captain Street. A parochial lunatic asylum stood on an adjacent site to the west.

Greenock original poorhouse site, 1857.

The Smithston Poorhouse

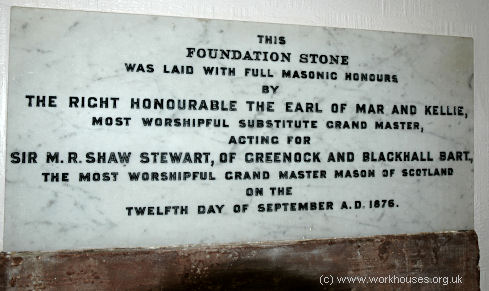

By the 1870s, the poorhouse was in such a state of decay that in 1876, the parochial board began construction of a new institution for 750 inmates at a site on the Inverkip Road to the west of Greenock.

Greenock asylum and poorhouse foundation stone, 2005.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The building's construction was described in an 1879 report in The Builder:

GREENOCK POOR-HOUSE AND ASYLUM.

A few years ago the building used as a poor-house and asylum by the Parochial Board of Greenock was condemned by the authorities as unsuitable, and that led to the erection of the handsome pile now approaching completion on the lands of Smithston, about a mile and a half to the south-west of the town, and which, when completed, will be one of the finest structures of the kind in Scotland. The site, which consists of 80 acres, cost about 7,000l., and the plan selected was that prepared by Mr. Starforth, architect, Edinburgh. The style of the main buildings is Scottish Baronial, with crow-step gables and corbelled. windows and turrets, the materials used being red sandstone from Mr. Kennedy's quarries, Wemyss Bay, with roofs of Cumberland slate. The buildings occupy about 5 acres, the main portion being divided into three sections, viz., the asylum to the east, the administrative department in the centre, and the poor-house to the west. The. north front faces the Inverkip-road, and is prominent in the view from the Wemyss Bay Railway. The length of this frontage is 336 ft.; the asylum being 108ft.; administrative department, 138ft.; and the poor-house, 90 ft. The east front of the asylum and the west front of the poor-house occupy 290 ft. respectively, but the administrative portion runs back 350 ft. The whole of the north front is, two stories in height, except the centre portion, which rises to three stories, and is surmounted by a tower, 90 ft. in height. Towers, also, rise to a height of 70 ft. from the east and west wings respectively. A similar arrangement as to height has been carried out in the plan of the east front, the centre having corbelled projecting chimneys and oriel windows, while a small tower, 50 ft. high, ornaments the south end. The height of the poor. house is three stories, two towers rising from the centre to an altitude of 90 ft. The interior of each of these towers has been available for the construction of tanks capable of storing 15,000 gallons of water.

The asylum will shelter 150 lunatic patients, and the poor-house 450 paupers ; while the accommodation for the officials is ample and complete. Such a system of classification has been adopted in the poor-house that the dissolute will be dissociated from what may be termed the virtuous poor. The dimensions of the paupers' dining-hall are 66 ft. by 36 ft.; of the asylum, 54 ft. by 30 ft., the ceilings of each being 23 ft. in height. The kitchen, which is to be fitted with the best modern appliances, is 31 ft. by 31 ft. 6 in., while the arrangements of the day- rooms, school, and dormitories are well adapted to secure the comfort of the inmates. Corridors run north and south through the poor-house on each flat. The infirmary, which stands to the west of the poor-house, and provides accommodation for 100 patients, is a two-story building 156 ft. long, with towers at each corner rising 52 ft. above the ridge. Communication under cover is arranged with this building, and with all parts of the main house. Twenty feet further west of the infirmary stands the detached contagious department, which will accommodate twenty patients, while to the south-east of the asylum is the probationary house, a two-story building for housing forty persons. The entire buildings are heated with hot air, while baths, lavatories, and out-offices are so arranged as to complete the plans. The contractors for the masonry work are Messrs. J. Coghill & Sons, and the buildings, the progress of which has been somewhat impeded by strikes and disputes, will be ready for occupation in a few months. The estimated cost of the new poor-house and asylum is 80,0001., to which there has to be added an additional 10,0001. which the Parochial Board is expending in the erection of a suite of new offices at the corner of west Stewart-street and Nicholson-street, Greenock. Mr. McLellan, architect, Greenock, is superintending the erection of the buildings at Smithston, which have recently been visited officially by the chairman and committee of management.

Greenock new poorhouse site, 1938.

As noted in the above report, the east side of the main building contained the asylum, the central part with its frontage to the north contained the administrative portion, and the west side held the poorhouse.

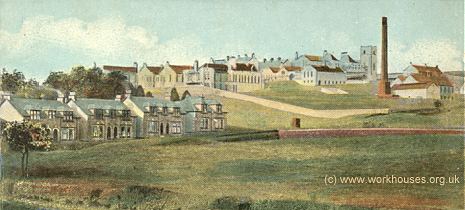

Greenock asylum and poorhouse from the north-east, 1911.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Greenock asylum section from the north-east, 2005.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Greenock administrative section from the north, 2005.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The poorhouse section has now been demolished, truncating the west end of the administrative block.

Greenock adminuistrative section from the north-west, 2005.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The expense of the new institution was criticised by many ratepayers who referred to the new institution as "The Palace of the Kip Valley". In fact, until the end of the century, the poorhouse inmates slept on straw palliases, and were fed a diet of soup, herring and bread, with potatoes, being a luxury, served only twice a week.

Greenock infirmary block from the north-east, 2005.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Greenock infirmary block from the north-west, 2005.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Greenock infirmary block from the south-west, 2005.

© Peter Higginbotham.

On Christmas Eve, 1884, the Greenock Telegraph reported the death of Mr John Hunter, the Chaplain of Smithston:

In 1885, Mr M'Neil, a Visiting Officer from the Board of Supervision, reported that:

An examination of the children showed that the cleanliness of the boys to be satisfactory, but the heads of the girls, although ostensibly tidy and well brushed, were in a horrifying and utterly disgraceful condition. The ova of vermin were present in large numbers; and I also observed live insects.

Greenock service blocks from the south-west, 2005.

© Peter Higginbotham.

During the First World War, part of the building was used for the treatment of military casualties invalided home from France and Belgium.

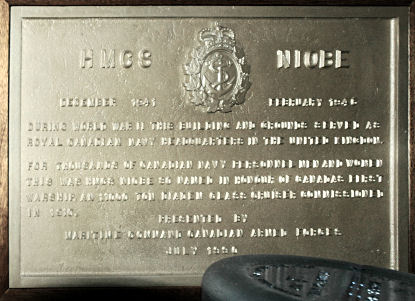

After 1930, the poorhouse became a Poor Law Hospital known as the Smithston. In 1939, the premises were requisitioned by the Admiralty, and in 1941 were taken over by as the UK headquarters of the Canadian navy. The Canadians renamed the hospital HMCS Niobe in honour of Canada's first warship, an 11,000-ton Diadem Class destroyer commissioned in 1910. This period is commemorated in a plaque presented to the hospital in 1990 by Maritime Command Canadian Armed Forces.

HMCS Niobe commemoration plaque, 2005.

© Peter Higginbotham.

With the advent of the National Health Service in 1948, the Smithston became Ravenscraig Hospital and has latterly provided care for the elderly and mentally ill.

Services at Ravenscraig are currently (2004) being run down prior to the closure of the hospital.

The original Greenock poorhouse buildings are long gone and the site is now occupied by a housing development.

Below are reminiscences by Bob Easton, who worked at Smithston/Ravenscraig for 35 years, starting work in 1934.

Ravenscraig at that time, you entered the front door - one side was all Poorhouse and the other was all Mental Hospital. A doctor ruled the Mental Hospital, and Governor, called GG Gibson, ruled the poorhouse, he came from the Prison Service.

If you were cut off the 'broo they went for the Poor Law Assistance, and they gave a grant or that, but if for some reason or another they thought you were drinking, or you weren't fit to handle money it was the Poorhouse or nothing. So a lot of them landed up there. And sooner or later they left, and then it repeated itself.

They were put to work, but a lot of them wouldn't work. You cannae force people to work that will not work. But in those days it was coal boilers and a lot of there were put on the coal, shovelling the coal up to the boilers in the boiler house.

They were put off at Nicholson Street, but they got a ticket for the Poorhouse. They weren't allowed to starve! But at the Poorhouse they got nothing. You had to do as you were told.

There used to be duels between the Governor on the one side and the Doctor on the other. They hated each other, sometimes you could use that to your advantage! (laugh)

At that time, you see all those fields around Ravenscraig, well, squads used to work those fields. There was a ploughman there and everything. The work squads, as they looked at it, was really for the good of the patients. It relieved the congestion on the ward from 9 till 12, and from 2 o'clock to 4, plus it put some of their energy, which they had a lot of, into other channels.

In the pre-war days it was more custodianship. There was very little trying to make them recover. In those days they believed you were mad for life, and they didnae do as they do now that they've got them classified as schizophrenic, depressives, melancholics and so forth. In those days it was just custodianship, and oh! we had some vicious cases. They could get very violent. We were under the Corporation then and they were very shrimp with their drugs, thormaldithide and bromide was nearly all. That just knocked them out. Dr Leggit was in charge then, two visits a day, and he could be called up during the day. They've made big advances in mental treatment now.

They went for big, strong men. We used to say that Ravenscraig was the capital of North Uist because half the men used to come from there! (laugh) Donalds, Frasers and Campbells, they wouldn't engage you if you were local. It was only during my time, 'cos they couldn't get the staff.

Getting attacked by patients was a regular thing in those days, when it became too much you'd run for the doctor and he decided whether you gave them a sleeping drug or not. My arm was once dislocated during an attack. I was just a student. Anyway they were going to dismiss me and that was it. finished. and I said "Oh Gee. where will I get a job with this useless arm". And here a miracle happened, and the dislocation went in itself, one night, it jumped in!

This gives you an example of how severe they were. I had a sort throat once and they wouldn't hear of you working in a hospital with a sore throat. So they sent for the doctor from Gateside, the Fever Hospital, and took a swab and said I'd diphtheria. I didn't believe I did, but they said the swab 'proved' it so they sent me to Gateside. I was only a student, on probation at the time. I thought I was going to loose this job. They kept me in for six weeks for the negatives to show, and I came out on the Saturday dinner time. I went over to see my chief, and he said he had to consult the doctor - he had all the power. You had to leave all your gear when you had diphtheria, you weren't allowed to take writing paper, shaving brushes, you had to leave it all there. I said 'I'll need to get out now and get new shaving gear' and all this, and he said 'well, we'll give you the rest of Saturday off, and you can start at six tomorrow morning'. That was the kind of treatment you got then, but we thought nothing of it. So after having been six weeks on my back, getting jags in the stomach to counteract the illness. It wasn't nice! It made you stiffen up for a long while, and after coming out on the Saturday afternoon I had to start at six the next morning!

We were equal to Sisters, we were Charge Nurses, with maybe two staff, not necessarily trained. And we had to decide how to run our hospital wards ourselves. The doctor was always the boss - the head. You had to deal with any ordinary illness, because they couldn't dare send' them to any other hospital. They were hard days, but of course it was a job!

Most of the staff slept in, you had wee rooms. Your wage was about £1 19 shillings - they took about £1 off for the room though. You got a uniform - something like a policeman's uniform. but with a big red stripe down the trouser leg. If you went out for a walk everybody recognised you with this big red stripe. So we tried to get this stripe taken out of our uniform. We fought for this. During such disputes we had to meet the Councillors. I thought it was awfae daft when one of them said 'How are we we to recognise the staff from the patients if they don't have this red' stripe'' Especially since the patients patients were wearing grey moleskins!

When we came back at the end of the war, we formed an entertainment committee. That was for the patients. We made the football field. It was all up and down and we made it level. Wt got squads of patients out and we shifted tons and tons of soil. Eventually we entered the local leagues. Of course you always had to yet the approval of the Doctor in charge. Bull. This was all credit to him without his effort. We were getting away from the old idea of custodianship, being shut up. And instead getting them out, getting them passes for the weekend getting them home, someone taking charge of them, getting entertainment, instead of just concert parties coming up now and then. We formed a bowling league and we used to visit all the other mental hospitals. And when we were on the football team, you had to have three patients in the team before they would allow it, we used to play all the local teams, and it even went as far as playing outside, on pitches that weren't in hospitals. All the other patients joined in as spectators.

We formed a small improvement committee. We did a lot, but got no thanks for it. The corridors that were open, we wanted covered. Wed did a lot. I think the staff in those days sacrificed an awful lot of their time. We improved the lot for the nurses. In the 1960s we got the females equal pay to the males. We got the retiring age changed. But there were bitter fights.

Greenock Combination Hospital

Greenock also had a separate "Combination Hospital" erected in 1906-7 at a cost of £70,000. It was located at the north side of the Inverkip Road, just to the north-west of the poorhouse. Its ayout is shown on the 1914 map below.

Greenock Gateside Hospital site, 1914.

Greenock Combination Hospital from the east c.1910

© Peter Higginbotham.

The opening of the hospital was the subject of a press report in January 1908.

ON Thursday last the new Combination Hospital erected at Gateside, Inverkip Road, Greenock, to serve the three burghs of Greenock, Port-Glasgow, and Gourock, and the-western portion of Renfrewshire, was formally opened by Provost Denholm, Greenock.

The site, which extends to ten acres, is an excellent one for the purpose. There are twelve different blocks of buildings, each intended to serve a specific purpose. The fever pavilions consist of wards for the treatment of enteric fever, typhus fever, diphtheria, measles, and scarlet fever (in which connection provision is made in separate buildings for the observation of doubtful cases, isolation of cases of doubtful infection, and a special block is reserved for the special treatment of patients a few days prior to their being discharged). At present the hospital provides accommodation for 118 adult beds which can be considerably increased in the case of children. Provision is made for a further extension of the scarlet fever wards to the extent of 44 beds, so that the completed hospital will be able to accommodate 162 adult cases. The buildings are of brick, and rough-cast on face, and the floors of the two-storey blocks are fireproof. In the wards, which are airy and well lighted, a novel feature is the introduction of circular instead of square ends. At the ends are the sanitary annexes and sun-rooms, the former separated from the wards by cross-ventilated lobbies. All internal corners and angles are rounded, in order that the whole place may be kept perfectly clean with a minimum of labour. At the end of each ward is a balcony with an escape stair, and in the event of fire the arrangements for the safety of the patients are as complete as possible.. All the wards are connected by means of covered ways. The heating of the building is on the Reck system, a radiator being placed at each window, with a direct air inlet, which can be regulated as desired. In the large wards the foul air is extracted by means of slow-moving fans, and the smaller wards have special air flues alongside the smoke flues. The buildings are lighted with electricity from Greenock Corporation supply. At the laundry, where the most modern machinery has been introduced, a steam disinfector and a destructor have been installed. Throughout, the buildings, fittings, and furnishings have been kept perfectly plain, and the total cost of the hospital will be about £400 per bed. When the Local Government Board approved of the designs, favourable comments were made as to the thorough and efficient manner in which the plans had been worked out, and, now that the buildings are completed, this opinion is stated as being fully borne out. The architect is Mr. Alexander Cullen, F.R.I.B.A., and the consulting engineer Mr. John Dixon.

At the opening ceremony, Mr. Cullen, on behalf of himself and contractors, presented Provost Denholm with a gold key for the main door of the administrative block, and thereafter the large company of ladies and gentlemen present assembled in the recreation room, where a number of speeches were delivered.

Staff

Inmates

Records

Note: many repositories impose a closure period of up to 100 years for records identifying individuals. Before travelling a long distance, always check that the records you want to consult will be available.

- The whereabouts of any surviving records poorhouse appears to be unknown. However, some records dating from around 1860 relating to the asylum/hospital part of the institution are held by Glasgow City Archives, The Mitchell Library, 210 North Street, Glasgow G3 7DN, Scotland.

Bibliography

- Government and Social Conditions in Scotland 1845-1919 by Ian Levitt (1988, Scottish History Society)

- The Builder 20th April, 1878.

Links

- None.

Unless otherwise indicated, this page () is copyright Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.