St Pancras, Middlesex, London

Up to 1834

St Pancras opened its first workhouse in 1731 in rented premises at the west side of King's Road (now St Pancras Way). By 1770s, the building was in a very poor state and in 1775 a lease was taken out on a property situated in the fork between what are now Camden High Street and Kentish Town Road , with frontages of over 250 feet on each. The premises included workshops, yards, gardens and an infirmary and in 1777 accommodated up to 120 inmates. The number greatly increased, however — in 1787, they were sleeping five or six to a bed and there were fears of putrid fever breaking out.

St Pancras workhouse site, 1786

A portrait of the St Pancras workhouse at this period is provided in John Waller's The Real Oliver Twist. The building itself, formerly a gentleman's mansion and later an inn, had a stately four-storey main block, a fair-sized chapel, and an "engine room", all surrounded by a six-foot high wall. Robert Blincoe, on whose story Dickens' Oliver Twist may be based, was a child inmate of the workhouse, which was overcrowded and bug-ridden. As well as being given a rudimentary education, Blincoe and his fellow inmates were sometimes set to work for 12 hours a day or more at the unpleasant task of oakum picking.

The workhouse's 1804 dietary table is shown below — fairly typical of workhouse diets of the period, and a far cry from the unremitting gruel of the workhouse presented by Dickens:

| Breakfast | Dinner | Supper | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sunday | Milk porridge | Mutton | Bread & Cheese |

| Monday | " " | Bread & Cheese | " " |

| Tuesday | " " | Boiled Beef | " " |

| Wednesday | " " | Barley Broth | " " |

| Thursday | " " | Boiled Beef | " " |

| Friday | " " | Barley Broth | " " |

| Saturday | " " | Peas soup with 4 oz beef | " " |

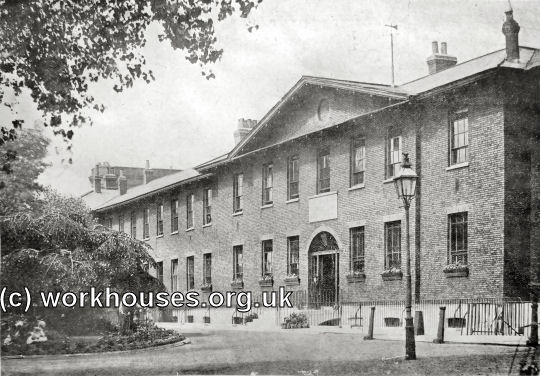

In 1804, in order to improve the administration of poor relief in the parish, whose population had greatly increased in recent decades, St Pancras obtained a Local Act, allowing it appoint a committee of Directors of the Poor, to employ paid rate collectors, and to erect a new workhouse. On being found to be inadequate for its purpose, the 1804 Act was repealed the following year and an enhanced version obtained. A site was obtained at the east side of King's Road (now St Pancras Way), just north of the parish church and construction of the new building, designed by Thomas Hardwick, began in 1806.The new workhouse was opened in 1809 and initially provided accommodation for 500 inmates. The two-storey main building was described as "a row of small houses, with a high red-brick wall in front, through which is an entrance gate surmounted by a lamp." In 1812, an infirmary was added to house the 160 inmates who had until then remained at the old premises.

The 1809 workhouse from the south, c.1889

© Peter Higginbotham.

St Pancras also adopted Hobhouse's Act of 1831, which provided for administration of the parish by an executive committee elected from the ratepayers.

After 1834

In 1836, St Pancras came into conflict with the Poor Law Commissioners who directed the parish to elect a Board of Guardians as provided by the Poor Law Amendment Act. St Pancras argued that, having adopted Hobhouse's Act, it was under no obligation to do so and wished to continue with its existing mode of poor relief administration. The parish successfully appealed to the Court of King's Bench and then continued operating as a Local Act Parish until 1867 when a Board of Guardians was established under the terms of the 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act.

After 1834, the parish continued using its existing workhouse at King's Road. The site layout is shown on the 1871 map below.

St Pancras workhouse site, 1871

The entrance was from King's Road at the south-west corner, with receiving wards placed a little way inside. The main building was a large U-shaped block facing to the south-west. The master and matron's quarters were at the centre, with females inmates housed at each side, and a chapel located on the ground floor of the northern wing. The male wards were placed along the south-east edge of the site, with imbecile and lunatic wards at the eastern corner. Casual wards, together with a stone-breaking yard were at the north-east side, and had their own separate entrance gate. An infirmary block, erected in 1848-9, stood at the northern corner of the site, with kitchen and nursery separating it from women's oakum picking rooms at the western corner. At the centre, surrounded by a garden area, stood the main kitchens, the bakehouse, and the laundry. A "dead house" or mortuary stood to the south-east of the workhouse, with an adjacent grave yard, disused by 1871.

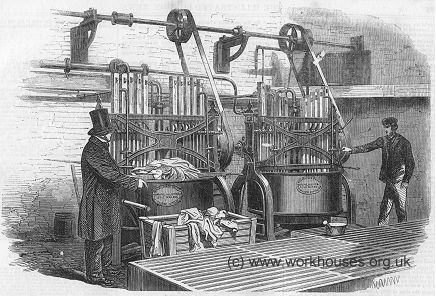

For large workhouses such as St Pancras, activities such as cooking and washing were performed on an industrial scale, often providing a useful source of labour to be performed by workhouse inmates. On occasion, however, the Victorian passion for mechanisation made inroads into these establishments. In 1857, the Illustrated London News reported on innovations in the St Pancras workhouse laundry.

St Pancras Laundry, 1857

© Peter Higginbotham.

STEAM WASHING MACHINERY AT ST. PANCRAS WORKHOUSE.

ABOUT twelve months ago the Directors of the Poor of St. Pancras, finding the then existing laundry arrangements very defective, decided on erecting a new laundry at the rear of the house, and on adopting the best description of washing machinery they could meet with. Inquiries were made, advertisements issued requesting patentees to forward descriptions of their machinery, and every step taken to obtain information on the subject. The result was the adoption of Macalpine's Washing machines and Manlove's dashwheel and hydro-extractor, — all to be driven by steam-power.

The number of inmates of the house varies from 1500 to nearly 1900, of whom about 200 are occupants of the sick wards, some sixty or seventy lunatics and idiots, and about 1000 inform and helpless aged persons. To supply these inmates there are more than 8000 articles to be washed every week. The machinery does this work most perfectly in four days each week.

The washing-machine is a circular iron vessel turning on a central shaft, with a "rachet" or intermittent motion. There is a false perforated bottom on which the clothes rest. Across the vessel a cumber of wooden beaters are suspended in a horizontal frame attached to the central shaft. While the vessel is moving round these beaters or "dollies" are raised. During the momentary cessation of motion in the vessel they fall upon the clothes. While the "dollies" are rising the clothes become saturated with the strong ley or suds contained in the vessel. The fall of the "dollies" drives out from the clothes the suds, and therewith the impurities also, which fall below the perforated bottom. This process continues ten minutes, or as much longer as may be occasionally necessary. During the process the water in which the clothes are immersed is kept boiling by the introduction of steam through the central shaft. By the simple intermittent motion given to the vessel the finest muslin may be washed without the slightest injury or abrasion of the texture.

The articles washed consist of every description of clothing and linen-rugs, blankets, caps, sheets, bed-ticks, lace collars, and other articles required by the inmates and officials.

The Dashwheel or Rinsing-Machine is a hollow flat cylinder revolving on its axis, and divided into compartments. The clothes, when cleansed, are placed in the several compartments of the wheel, into which jets of water are discharged while the wheel is rapidly revolving. The clothes are then tossed from side to side, being at the same time exposed to the cleansing and rinsing action of the jets of clean water, provision being made for the rapid escape of the water.

The Hydro- Extractor consists of a wire cylinder caused to rotate at a great velocity — 900 revolutions per minute — into which the wet clothes are placed; when the cylinder acquires centrifugal force sufficient to throw off so much of the moisture that when taken from the machine it is impossible for a strong man to "wring" a drop of water from the clothes, or even from blankets. Attached to the laundry are drying-rooms heated by steam passing through a series of pipes under an open batten floor.

By simple and ingenious means the supply of cold air and the escape of the heated air can be controlled to a nicety, and a constant upward current of heated air can be maintained until the clothes are not only dried but sweetened. These drying-rooms render the laundry operations independent of the weather.

The whole arrangement has been carried out, under the instructions of the directors, by Mr. W. B. Scott, the chief surveyor to the vestry, in a most able manner.

The same class of machinery has been erected at the Wellington Barracks, St. James's Park (where the washing is done for all the metropolitan barracks), at the Nottingham Union Workhouse, at several bleachworks in Scotland, at Aldershott Camp, at Portsmouth, at Birmingham, and many other places.

During the late war, two of the machines were sent out and erected at the hospital in Smyrna, and subsequently removed to Scutari, where they were much approved of by Miss Nightingale.

Despite such innovations, conditions for the inmates and staff left much to be desired. In 1856, an investigation was carried out for the Poor Law Board by Dr Henry Bence Jones, into conditions in the workhouse. Dr Jones had found that workhouse was severely overcrowded with patients in the infirmary having to be placed on the floor. Ventilation throughout the building was deficient, with fetid air from privies, sinks, drains, urinals and foul patients permeating many of the wards and producing sickness, headaches and dysentery amongst the inmates. The staff also complained of nausea, giddiness, sickness and loss of appetite. A lying-in room, also used as a sleeping room by night nurses, had a smell that was 'enough to knock you down'. In the women's receiving wards, more than eighty women and children slept in two rooms which provided a mere 164 cubic feet of space per adult. Worst of all were the underground 'pens' where between 300 and 900 applicants for out-relief crowded each day, sometimes waiting until 7 p.m. without food. The poor ventilation and smell in the pens was so poor as to cause women to faint and windows to be broken to obtain fresh air. The union's relieving officer reported that his predecessor had died of typhus, thought to be contracted from the foul air. Dr Jones' heartfelt conclusion was that 'such a state of things ought not to be tolerated by the Government.'

A decade later, things were little better. In December 1865, St Pancras was the subject of one of a series of articles in the medical journal The Lancet investigating conditions in London workhouse infirmaries. The report revealed a variety of problems which its authors summarised as follows:

1. We report that the wards of the infirmary proper and the insane department are in themselves deserving of praise; but that the infirm wards, the nursery, and the lying-in wards, are by their construction unfit for the reception of sick persons.

2. All the wards are deficient in their allowance of cubic space, even when but moderately filled; and the practice of overcrowding, which has been customary in the winter season, must render the wards in which it occurs unhealthy.

3. The furniture and conveniences, even of the infirmary wards, are insufficient; that of some of the infirm wards very decidedly so. The water closets are in several cases highly objectionable.

4. The nursing department requires further development by the engagement of additional paid nurses, and particularly by the establishment of a proper system of night-nursing.

5. The medical staff ought to be considerably augmented.

6. The present large insane department ought to be abolished, and only such cases of mental disease should be admitted as are chronic, incurable, and perfectly harmless. All cases of mania, of melancholia, of insanity from drink, and of epilepsy, ought to be sent to the county asylum.

On the whole, we are able to report that the St. Pancras infirmary is one of those which might, with certain modifications of structure, and with an improved management, be developed into a good pauper hospital. This being the case, we regret to learn that it probably cannot be retained, but will be sold to a railway company.

The full text of the Lancet report is available on a separate page.

Further bad press followed in 1868 in another Illustrated London News report:

Taking heed of its critics, St Pancras decided to establish a new infirmary on a separate site at Highgate (see below).

In 1881, extra land was acquired adjacent to the King's Road workhouse with a view to rebuilding the workhouse, and plans were drawn up by HH Bridgman.

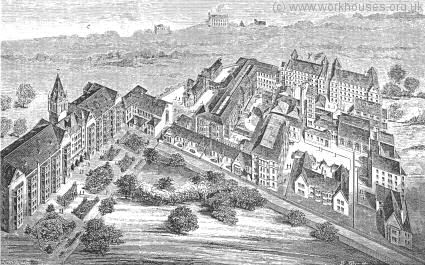

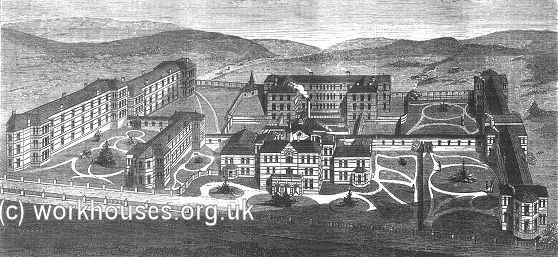

Bridgman's scheme for new St Pancras Workhouse from east, 1882.

However, Bridgman's scheme was not carried out as planned. Instead, a long period of piecemeal construction took place, with old and outdated buildings gradually being replaced. One part of Bridgman's scheme that was built was a large block for chronic, infirm and bed-ridden patients at the south of the site. It was originally known as the Cook's Terrace block, and later as the South Wing. Completed in 1885, it accommodated 400 inmates.

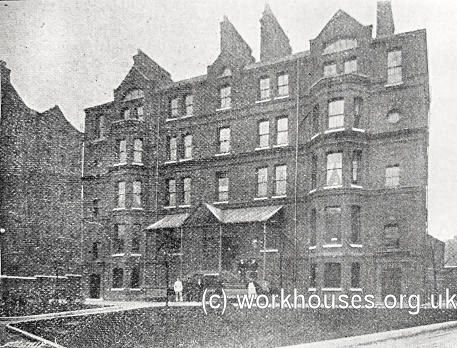

St Pancras workhouse infirmary South Wing from the west.

St Pancras workhouse infirmary South Wing from the west, 2001.

© Peter Higginbotham.

In 1890-6, a number of buildings designed by A & C Harston were erected. Male and female admission blocks were erected to the north and south of the King's Road entrance. The male block was damaged during the Second World War and later demolished. An administration block was erected behind the male admissions block, replacing the main 1809 workhouse building. This too was demolished after bomb damage.

St Pancras new administrative block, c.1897.

© Peter Higginbotham.

St Pancras entrance from the west, 2001.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Four large dormitory blocks were erected in 1890-5, the one nearest the entrance serving as a nurses' home.

St Pancras dormitory blocks from the west, 2001.

© Peter Higginbotham.

St Pancras dormitory block foundation stone, 2001.

© Peter Higginbotham.

St Pancras male infirm wards, c.1897.

© Peter Higginbotham.

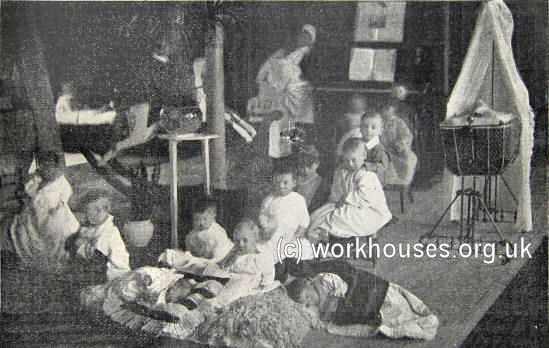

St Pancras children's ward, c.1897.

© Peter Higginbotham.

In 1899, separate chapels for Anglican and Roman Catholic inmates were erected at the rear of the female admissions block.

St Pancras Roman Catholic chapel from the north-west, 2001.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Various utility buildings ran down the centre of the site.

St Pancras laundry and kitchen blocks from the south, 2001.

© Peter Higginbotham.

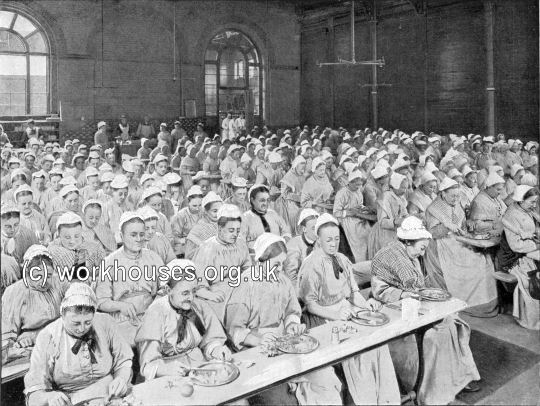

Separate male and female dining halls backed on to the workhouse kitchens.

St Pancras workhouse dining hall, 1897.

St Pancras workhouse kitchens, c.1897.

The later site layout in shown on the 1916 map below. The main entrance was at the west on King's Road.

St Pancras Site, 1916

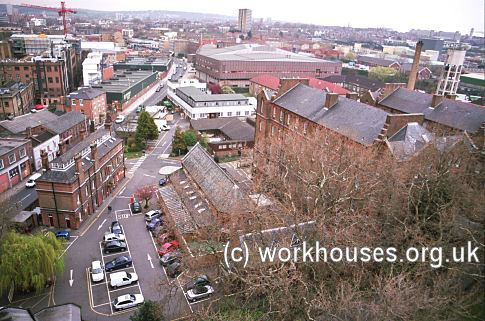

St Pancras site from top of South Wing, 2001.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Life for the workhouse residents was not entirely bleak. In January 1897, over 1,000 of the inmates attended a concert in the dining-hall arranged by the chairman of the Board of Guardians, Mr Nathan Robinson. Afterwards, the inmates were presented with a total of 1,150 half-pounds of cake, 450 ounces of tobacco, and oranges and apples.

From 1904, to protect them from disadvantage in later life, the birth certificates for those born in the workhouse gave its address just as 4 Kings Road, St Pancras.

The former workhouse site is now St Pancras Hospital with many of the old buildings still surviving.

Highgate Infirmary

In 1868-70, St Pancras erected a new infirmary on Dartmouth Park Hill, Highgate. Not long after its opening, St Pancras became a member of the recently formed Central London Sick Asylum District. The other members of the District (the Westminster and Strand Unions and the parishes of St Giles-in-the-Fields and St George, Bloomsbury) then made use of the infirmary which was sometimes referred to as the Central London Sick Asylum.

The infirmary was one of the first in London to be built on a separate site away from its parent workhouse. The infirmary's architects, Messrs. John Giles & Biven, took advice from Florence Nightingale and put into practice the ideas she had formulated in her 1863 publication Notes on Hospitals:

These principles led to the evolution of the "Nightingale ward block" — an elongated structure, typically of two or three storeys, where windows and beds were alternated along each wall, each pair of opposite windows providing a through current of air but without placing patients in a direct draught or sun. The height and width of the ward, and the number and of beds, were calculated to optimise the light and airflow. Nightingale wards were typically 96 feet long, 24 feet wide, and 12 feet high, with 32 beds. The entrance and nurse's station were at one end, with baths, toilets, and escape stairs at the other. Miss Nightingale subsequently remarked that Highgate Infirmary was the "finest metropolitan hospital" She was also instrumental in the appointment of the first matron, Miss Mabel Torrance, and the first twelve nurses were trained in her own school for nurses at St Thomas's Hospital. Highgate subsequently became the home of London's first poor law school of nursing which was set up in association with the Nightingale Fund.

The Highgate infirmary's design was described in a contemporary report:

This Infirmary is now being erected at Highgate on a site containing about 3¾ acres of land. On the highest or north side of the ground is placed the central or administrative block, extending from north to south. In the front portion are placed the porters' rooms, and immediately joining them are the male and female receiving-rooms, with water-closet and bath in each. Right and loft of these are the dwellings of the resident surgeon and assistant surgeon, and matron, with bed-rooms, &c., in the floor above. On the other side are the Board and waiting rooms, with lavatory attached. The matron's linen-room, &c., are on this side also.

The centre is occupied, as will be seen on reference to the plan, by the store department, with steward's office overlooking. By the natural fall of the ground ample space is obtained for wine, beer, and other cellars beneath without excavation. The kitchen, scullery, and larders are adjoining, and occupy the centre of the entire range of buildings.

On either side of the corridors are the steward and male servants' mess-rooms, and the matron's and female servants' mess-rooms. The steward has a separate and a distinct house on the right of the main building, overlooking the entrance to the stores. The dispensary and operating-rooms are situated on the side of the intersecting corridor, between the male and female block; on the other side of the door dividing the cross corridor is the boiler-house, with stairs to coal-store below. A patients' clothes-store is close at hand here, entered from the covered way outside the building, which leads to foul wards.

The laundry is approached by steps necessitated by the fall of the ground; these steps are divided in the middle from the male and female sides. Dry-houses for drying the clothes are provided for, and in addition a spacious drying ground adjoins the laundry. All these buildings are lofty, and ventilated by top draughts. Beyond this laundry, and entirely detached from the rest, is a wash-house for foul linen, with fumigating-room, under which is a large tank for storage of rain water. W.C.s and urinals in convenient positions are placed throughout the buildings.

The patients' blocks are placed on either side of the main block — the three blocks for females on the left, the two for males on the right. Accommodation for 256 females is provided in two wards of three stories each and one of two only — 32 beds in each ward. For male patients there is one block of three floors and one of two, providing for 160 patients. The wards are 22 ft. wide and 13 ft. 6 in. clear height, and are lighted by windows on either side, reaching within a foot of the ceiling; the upper part of the window is made to fall open for ventilation. Open fireplaces are used for warming, the air before passing into the wards being heated by circulation round the stoves. Each ward has a staircase, with nurses' room overlooking ward and ward scullery, sink, and lift from corridors below for linen, food, &c.; a linen-store and nurses' W.C. at the one end of it, and shutes and dust for foul linen. At the other, on one side are a bath-room and lavatory for patients, and W.C.s in the other, thoroughly ventilated by through draughts. At the extreme end is a dayroom for the use of convalescent patients, with easy access from ward.

The foul wards are entirely isolated, and contain accommodation for 64 patients of each sex, or 108 in all. They have lavatories, W.C.s, nurses' rooms, and sculleries for each particular class.

The dead-house is at the south-east corner of the ground, with the necessary post-mortem rooms, &c., and removals can be made without the necessity of going near the main buildings.

The staff of nurses will, we understand, be provided by the Nightingale Training Institution.

This infirmary is being erected for the St. Pancras Board of Guardians, of which Mr. W. H. Wyatt is the chairman, from the designs of Messrs. John Giles & Biven. The contractor is Mr. W. Henshaw, whose contract amounts to 18,000l. The clerk of works is Mr. Culverhouse.

St Pancras Highgate Infirmary, 1869.

Former St Pancras Highgate Infirmary Administration Block from the north-east, 2004.

© Peter Higginbotham.

St Pancras Highgate Infirmary, 1869.

St Pancras Highgate Infirmary, 1869.

Former St Pancras Highate Infirmary Female Ward Block from the north, 2004.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Florence Nightingale took a continuing interest in Highgate Infirmary and wrote over 100 letters to Mabel Torrance and her successor, providing advice on nursing issues. She demanded that her nursing recruits "must be, of course, of unimpeached character" — she would not take women who "would never be anything much better than scrubbers". If the 1881 census is anything to go by, the hospital appears to have had a striking fondness for nurses and ward assistants who originated in Wales!

In 1883, St Pancras left the Central Sick Asylum District and the site returned to the parish's sole use as its North Infirmary, making it London's only Board of Guardians with two large purpose-built infirmaries at its disposal.

St Pancras Highgate Hill Infirmary site, 1913.

In 1901, Edith Cavell was appointed Night Sister and stayed at the infirmary for three years. During this time, as Night Sister in charge of over 500 beds, she was the only trained nurse on duty. Later, during the First World War, Miss Cavell was shot in Brussels by the Germans as a spy.

In 1904, as with the main workhouse, the infirmary acquired a euphemistic address for use on birth (and later death) certificates of "199 Dartmouth Park Hill".

Here is a view of the infirmary from the early 1900s.

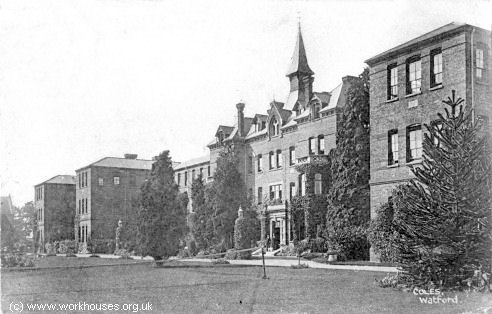

View of St Pancras Highgate Infirmary, early 1900s.

© Peter Higginbotham.

And the same view a century later...

View of Former St Pancras Highgate Infirmary, 2004.

© Peter Higginbotham.

In 1930, control of the site passed to the London County Council. By 1945, it had become grouped with the adjacent St Mary's Hospital (former Islington Union infirmary) and Archway Hospital (former Holborn Union infirmary) under a single administration. With the advent of the National Health Service in 1948, the three sites became the Highgate, St Mary's, and Archway wings of the Whittington Hospital.

In 2003-4, the site was redeveloped as the Highgate Mental Health Centre incorporating many of the old buildings.

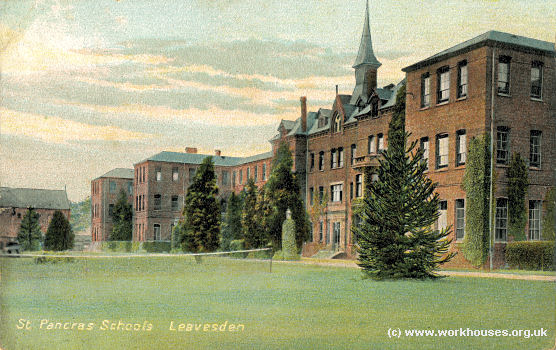

St Pancras Industrial Schools, Leavesden

In 1868, the St Pancras Guardians embarked on the erection of a new industrial school for pauper children in the parish. The acquired a 38-acre site in a rural location at Leavesden to the north of Abbots Langley. At about the same time, the recently formed Metropolitan Asylums Board was erecting its new Leavesden Asylum for Imbeciles on an adjacent site.

The location and layout of the school are shown on the 1890s map below.

St Pancras School site, 1895."

A porter's lodge lay at the north of the site. It contained a room where parents holding a pass from the guardians' offices in London could visit their children.

St Pancras entrance lodge from the north-east, 2004.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Opposite the lodge was a quarantine block where new arrivals stayed for at least three weeks. A drive then led past the main buildings, chapel, infirmary, and isolation hospital. Beyond this were a former infectious infirmary, later used as a nursery for three to five year olds, and a second quarantine cottage.

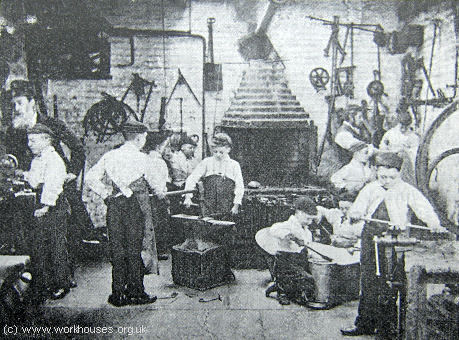

The main building, which occupied a total of 3.5 acres, had an administrative section at the centre containing dining-hall, kitchen, baker, two swimming baths, with a laundry and water tower to the rear. At the northern side were the boys' school, workshops and playground; the girls' school, day-room and playground were at the south. Infants were placed at the front of the building on the girls' side. The dormitories all lay on the two upper floors at the front of the building overlooking the field. As a result of the fire at the Forest Gate school, iron fire escapes from the dormitories were fitted to the outside of the building. Each child had its own bed with a horsehair mattress, pillow, three blankets and sheets.

St Pancras School from the south-east, date unknown.

© Peter Higginbotham.

St Pancras School from the east, c.1905.

© Peter Higginbotham.

St Pancras School from the east, c.1908.

© Peter Higginbotham.

St Pancras School from the south, c.1905.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The School was certified to hold 678 children. In November 1896, there were 615 in residence: 262 boys, 209 girls, and 144 infants.

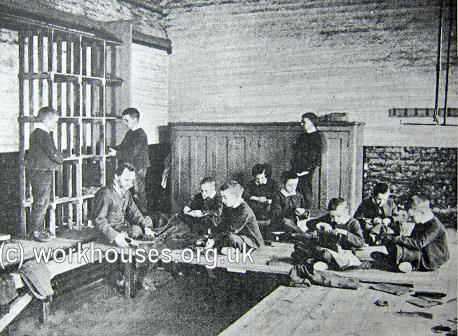

Children under nine rose at 6.30am, those over nine at 6am. The under-fives went to bed at 6pm, the under-sevens at 7pm, the under-nines at 7.30pm, and the under-fourteens at 8pm. On rising, the children dressed, said their prayers, then went down to wash in the lavatories. At 7.30 they assembled in the dining-hall, said grace, then began breakfast which consisted of bread, butter, treacle, or dripping, and milk. Talking was, by 1896 at least, freely encouraged. Any child still hungry at the end of a meal could raise their hand for extra bread. Between breakfast and school-time, all children over seven were required to do an hour's work of some sort. School began at 9am.

St Pancras School boy tailors, c.1896.

© Peter Higginbotham.

In the boys' school, lessons included scripture, grammar, recitation, tonic-sol-fa singing, geography, mental arithmetic, object lessons and drawing. In 1896, the boys' teaching staff comprised the Westminster-trained headmaster and four assistant masters. The teachers also took turns in supervising the children out of school hours, assisted by the drillmaster who also taught swimming. Playhours were spent in cricket or football or, in rainy weather, in a covered playground. In the evenings, they read adventure books and were given the occasional copy of the Daily Graphic. Elder boys were allowed to go picnicking in Bricket Woods.

St Pancras School blacksmith's shop, c.1896.

© Peter Higginbotham.

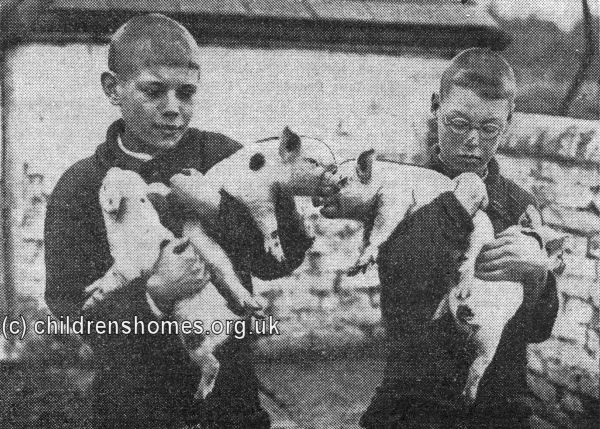

St Pancras School, boys raising pigs, 1917.

© Peter Higginbotham.

School for the girls began with 30 minutes religious instruction followed be lessons in reading, writing, grammar, composition, 'word-building', recitation, object-lessons, and needlework. In 1896, the girls' teaching staff comprised the headmistress, three assistant teachers, and a needle-mistress. A drill-mistress gave lessons in drilling and swimming. Girls about to leave for service had a small training kitchen where they were taught housework, cooking and dressmaking.

St Pancras School dressmaking class, c.1896.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The school originally had a general infirmary for treating ophthalmia, ringworm, eczema and other non-infectious conditions, together with a separate building for infectious cases. The latter was later converted for use as an independent intermediate school and replaced by a new building. Children requiring special treatment or operations for defective eyesight were sent from time to time to University College Hospital. A dentist visited three times a year.

St Pancras School, c.1896.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The school later became Abbots Langley Hospital which closed in the early 1990s. The site has now been redeveloped for housing and virtually all the old buildings demolished. The former lodge survives at the north of the site.

Eastcliff House Convalescent School, Margate

In November, 1895, after many years of sending recuperating children to various seaside schools, the St Pancras Guardians decided to set up their own seaside convalescent home/school at Margate. To this end, they purchased Eastcliff (or East Cliff) House, was located at the corner of Alexandra Road and Wilderness Road. Eastcliff House, with its accompanying garden and field, had for many years been used as a school for the sons of gentlemen. It accommodated around forty children taken from the St Pancras workhouse, infirmary and the Leavesden Schools.

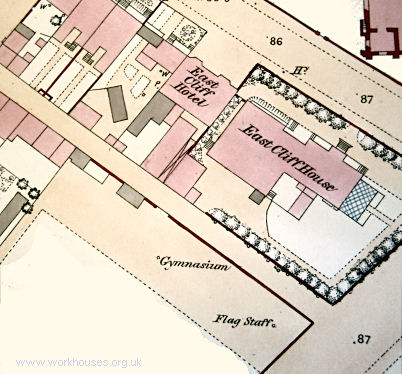

Eastcliff House site, 1873

Eastcliff House children and nurses, c.1896.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Eastcliff House from the north-east, 2005.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The Superintendent (in 1896 Miss EK Jacob) was a trained nurse, with two nurses under her. A schoolmistress was also employed during school hours, who also took the children out walking.

In 1898, the establishment was sold to the Metropolitan Asylums Board for use by all London's children. It was enlarged in 1901, 1903 and 1919, eventually becoming the Princess Mary's Hospital for Children. In the 1930s, it became a women's convalescent home.

Sun platform at Princess Mary's Hospital, Margate c.1930

© Peter Higginbotham.

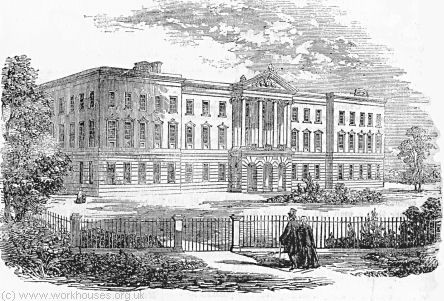

St Anne's Home, Streatham Hill

From around 1888 to 1915, St Pancras accommodated aged and infirm males in a branch workhouse at Streatham Hill known as the St Anne's Home. St Anne's had previously been the Royal Asylum of St Anne's Society, erected in 1829 to provide care and education for poor children. The building was a handsome edifice of three stories, surmounted by a cornice and parapet, and fronted centrally by an Ionic portico and pediment, ornamented with the royal arms. It was originally taken on by the St Pancras guardians as temporary accommodation while the main workhouse was being rebuilt in the early 1890s.

St Anne's Home, 1857.

The site's location and layout are shown on the 1894 map below.

St Anne's Home site, 1894.

The 1901 census records 496 inmates in residence at St Anne's. The establishment was taken over by the Bermondsey Union in around 1915.

Holmes Road Casual Ward

St Pancras operated a casual ward for vagrants on Holmes Road in Kentish Town. The building is now used as a hostel.

Holmes Road site, 1894.

Holmes Road former casual ward from the north-east, 2010.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Holmes Road former casual ward, rear section from the north-west, 2010.

© Peter Higginbotham.

St Margaret's Receiving Home, Leighton Road

In the early 1900s, St Pancras operated a children's receiving home at 25 Leighton Road in Kentish Town.

Staff

Inmates

- Long-term workhouse inmates (1861)

- St Pancras workhouse — 1881 Census

- Highgate infirmary — 1881 Census

- Leavesden Schools — 1881 Census

Records

Note: many repositories impose a closure period of up to 100 years for records identifying individuals. Before travelling a long distance, always check that the records you want to consult will be available.

The Ancestry UK- Ancestry: London Workhouse Admission/Discharges (1764-1930)

.

- London Poor Law and Board of Guardian Records (1738-1930)

.

- St Pancras Workhouse — Admissions/discharges (1868-72, 1916-30); Births (1871-1923); Baptisms (1874-82, 1898-1904); Deaths (1871-1909); Creed registers (1869-1929)

- South Infirmary — Admission and discharges (1920-36); Creed registers (1902-24); Deaths (1915-22).

- Highgate Infirmary — Admissions and discharges (1889-1911); Deaths (1870).

- St Anne's Home — Creed registers (1892-1914).

- Leavesden School — Admissions and discharges (1870-1932); Creed registers (1870-1931); Lists of pauper children (1870-1931).

- St. Margaret's Leighton Road Receiving Home — Admission and discharge registers (1916-18); Creed registers (1904-18).

- Plaistow Schools — Creed registers (1868-70).

- Darenth Schools — Admission orders (1891-6).

Bibliography

- Higginbotham, Peter Workhouses of London and the South East (2019)

- Monnington, W and Lampard, FJ (1898) Our London Poor Law Schools (London: Eyre and Spottiswoode)

- Waller, John (2005) The Real Oliver Twist: Robert Blincoe - A Life That Illuminates an Age Cambridge: Icon Books.

Links

Unless otherwise indicated, this page () is copyright Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.