Banbury, Oxfordshire

Up to 1834

Banbury had a workhouse at the east end of Scalding Lane from as early as 1643 (VCH, 1954), although it may have only been used for providing housing rather than employment.

In 1684, Joshua Sprigge left money for the building of a workhouse and buildings on the east side of South Bar were eventually bought for this purpose. For some years, the parish vestry employed Richard Burrowes to run the workhouse — he was to set 50 paupers between the ages of 8 and 60 to work manufacturing worsted. They received sufficient wages, clothes and food so that they would not become chargeable to the borough.

Over the years, various arrangements were tried for running the workhouse: in 1740 the governor received an annual allowance to cover all costs; in 1743 a weekly per-head payment for each inmate; in 1756 a per-head payment plus the profits from the inmates labour; in 1780, the governor received a simple salary of £25 a year and the vestry covered the workhouse running costs. Annual allowances ranged from £120 prior to 1731, to £600 in 1787. Weekly per-head allowances ranged from 1s. per pauper in 1743 to 2s. in 1783.

A Parliamentary report of 1777 recorded a parish workhouse in operation in Banbury with accommodation for up to 60 inmates, while Bloxham's workhouse could hold up to 35. East Adderbury's workhouse, which dated from around 1750, was listed as having a capacity of 12.

Bloxham former parish workhouse, 2003

© Peter Higginbotham

South Newington had a parish workhouse at the east side of the High Street. A house there is still known as Workhouse Cottage.

Banbury was the subject of a report in Eden's 1797 survey of the state of the poor in England:

. . .

It is much to be lamented that in a country where wages are not high enough to enable the Poor to supply themselves with wheaten bread, strong beer and butcher's meat they have not the means of eking out their scanty portions by culinary contrivances. The extreme dearness of fuel in Oxfordshire compels him to purchase his dinner at the baker's, and from his unavoidable consumption of bread he has little left for clothes in a country where warm clothing is most essentially wanted. Some slight attempts to prevent the removal of corn which have lately been made at Banbury are certainly ascribable to the pinching wants of the people. The arrival of the military prevented more serious consequences taking place. The manufactures of this town are chiefly exported to Russia. Trade has been very dull for some years, but has lately revived. Some considerable orders have been received, and trade is a little brisk again, though still the weavers have not full employment.

In the 1820s, with a decline in the wool industry, the vestry negotiated with a Henley silk-merchant to set up a silk factory in a a warehouse in the churchyard, employing up to 200 children. This seems not to have reached fruition, however.

Neighbouring Neithrop had a workhouse in Gould's square from at least 1803 when it housed 50 inmates. In the early 1800s, it saw large increase in expenditure on the poor, which may have been caused in part by overspill from Banbury.

After 1834

Banbury Poor Law Union was formed on 3rd April 1835 and comprised 38 parishes. However, within the first year of its existence, a further 13 parishes joined the union. Its operation was overseen by an elected Board of Guardians, 58 in number, representing its 51 constituent parishes as listed below (figures in brackets indicate numbers of Guardians if more than one):

Oxfordshire:

Alkerton, Banbury (4), Barford St John, Barford St Michael, Bloxham (2), Bodicott, Bourton Great and Little, Broughton,

Clattercott, Claydon, Cropredy, Drayton, East Adderbury, East Shutford, Epwell, Hanwell, Hook Norton (2), Horley, Hornton, Milcombe, Milton, Mollington, Neithrop (2), North Newington, Prescott, Sibford Ferris, Sibford Gower, South Newington, Swalcliffe, Tadmarton, Wardington, West Adderbury, West Shutford, Wigginton, Wroxton & Ballscott.

Later Additions: Grimsbury.

Gloucestershire:

Shenington.

Northamptonshire:

Appletree, Ashton-le-Wall, Upper Boddington, Lower Boddington, Chalcombe, Middleton Cheney (2), Chipping Warden, Warkworth with Middlecote and Grimsbury.

Warwickshire:

Avon Dassett, Farnborough, Molington, Radway, Ratley, Shotswell, Warmington.

The population falling within the enlarged union at the 1831 census had been 26,859 — ranging from Calttercott (population 9) to Banbury itself (3,737). The average annual poor-rate expenditure for the period 1832-35 had been £26,556 or 19s.9d. per head.

The new workhouse, for 300 inmates, was built in 1835 at a site on the north side of Warwick Road at Neithrop. The six-acre site was bought for £1,050 from Mr Charles Brickwell. The building was designed by Sampson Kempthorne and was built by the local firm of Danby & Taylor at a cost of £4,580. Architect's fees and other expenditure took the total cost of the scheme to around £6,200.

Banbury workhouse site, 1922.

The new workhouse, like other Kempthorne designs for unions such as Abingdon and Bradfield had a hexagonal outline plan as can be seen on the above map from 1922.

In Banbury, as in many other places, the New Poor Law caused much discontent amongst those who were no longer receiving relief. Relieving officers, who were at the sharp end of this ill-feeling, complained of being mobbed and obstructed in the execution of their duties. On Michaelmas Fair Day in 1835, following threats of damage to the new building, fifty special constables were sworn in at the workhouse, although nothing seems to have transpired. Three watchmen were also employed over the following December and January.

On April 5th 1838, local entrepreneur William Potts launched a new publication The Guardian; or, Monthly Poor Law Register to report the proceedings and activities of the Poor Law unions in the area. In its first issue, it noted that the Banbury workhouse population had reached a record total of 282 in the previous January, due in large part to the very bad weather at the time. In 1843, it was refounded as the Banbury Guardian newspaper, which is still in existence.

(Click on the image for an enlarged view.)

On April 5th 1838, local entrepreneur William Potts launched a new publication The Guardian; or, Monthly Poor Law Register to report the proceedings and activities of the Poor Law unions in the area. In its first issue, it noted that the Banbury workhouse population had reached a record total of 282 in the previous January, due in large part to the very bad weather at the time. In 1843, it was refounded as the Banbury Guardian newspaper, which is still in existence.

(Click on the image for an enlarged view.)

Like most workhouses, Banbury had to deal with its share of travelling vagrants who were allowed to stay a night in return for work — in later years, this was often digging the institution's gardens.

Banbury Reception centre

Courtesy of Newsquest (Oxfordshire) Ltd.

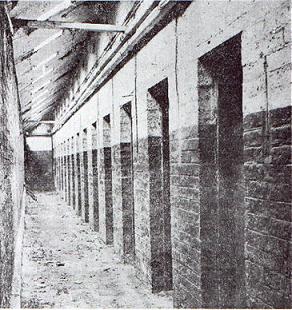

The "Reception Centre for Wayfarers" lay alongside the Warwick Road (see map above) and contained two blocks of cells.

Reception Centre Cells

Courtesy of Newsquest (Oxfordshire) Ltd.

Banbury was one of the workhouses visited undercover by Oxford MP and newspaper proprietor Frank Gray who disguised himself as a tramp. He was initially touched to be greeted by a porter who said that his trousers were not thick enough for the weather and he was provided with a luxurious bath. However, his later treatment failed to live up to this and he ultimately concluded that, "They do not desire to be cruel. They have simply lost interest in the unending procession of degraded men who present a problem which they do not understand and for which they have no remedy." (Fenby, 1970)

During the First World War, the workhouse was home to 200 German prisoners of war. They were employed in building a bridge across the Warwick Road and the Ironstone railway.

From 1948 to 1958, the institution — now known as Neithrop Hospital — came under the National Health Service. It was then run by the National Assistance Board until 1961, when the buildings were handed back to the hospital's Management Committee.

Neithrop Hospital, early 1980s. © Oxfordshire Photographic Archive.

In the mid-1980s, the hospital's facilities (it was now a geriatric unit) were transferred to the main Horton General Hospital. The old building was then demolished.

Horley Children's Home

Prior to 1914, the union's pauper children resided at the workhouse. Originally, they were taught by the workhouse schoolmaster or schoolmistress, then later went out each day to local elementary schools. In August 1914, the Board of Guardians agreed to rent a cottage and land at the south end of Horley from a Mr Fox, for use as a children's home. It was decided that no child would remain in the workhouse after March 1915 and in 1919, the property was purchased by the union. It was home to 20-24 boys and girls, and according to William Potts 'under capable foster parents, and in the happiest of circumstances'. Also from 1919, the original home (now known as 'The Lawn') housed boys, while a neighbouring property ('Greystones') housed girls - in later years, dormitories for the older boys are believed to have been placed in Greystones.

In around 1929, just before the Oxfordshire Council took over the running of the establishment, Harry (Henry) Austin, his brother George, and sisters Enid and Eileen, were taken to the Home. Their mother had 'left', and their father, Arthur, was unable to care for them alone, as he was a farm worker, the oldest of the children was seven, and the family were living in quite poor circumstances. Arthur spent many years living in Banbury Workhouse, and eventually died there. But he kept in contact with his children. They all grew into happy healthy adults, and for the time Horley Home gave them a better start than many would have had, given their circumstances. Below are Harry's recollections, recorded in May 2006, of their time in the home:

Aunt Em gave us soup and bread and then a cart came to take us to the home.

I thought the home was quite good. The boys and girls lived together, there were more boys than girls. Except for the older boys, who lived separately in another house, we all slept in dormitories, separate for girls and boys.

The Master was called Mr. Hartop, the Cook was Miss Pell. Both had been at the home for many years.

We had buckets for toilets, which had to be emptied every day, with separate arrangements for the girls.

We all had a 'Sunday Suit' for church and Sunday School. We went to church twice on Sunday. After church we had to hang up our best suit for the next week. The rest of the time the boys wore corduroy trousers, all the same, and boots.

At night we had to clean our shoes. They were checked by the older boys and if we didn't do them properly we had to do them again.

The breakfasts were quite nice. We had porridge and a boiled egg. But on a Saturday morning we had either Epsom Salts or Syrup of Figs. Not very nice.

We all went to Horley School. The teachers were Mrs. Pearson (head), Mrs Jackson and Mrs Humphries. If you didn't do what you were told to, you were put into the Infants class.

Some children at the school came from Hanwell, they had to walk from there.

Some boys used to run out of the school with no shoes on - they got a 'good hiding'. Punishment in the home, (a good hiding), meant trousers down and a smacking with the hand.

Every Saturday morning I used to clean the chickens out for the Master. He gave me a penny. He also used to give me a penny for weeding the drive and picking up the fallen apples.

Although Dad was in the workhouse he used to send us all sixpence with Mr. Sumners bread van from Hornton on a Saturday. The Matron used to give us a penny a day to spend at Mathews shop from the money that Dad had sent in the basket.

One day I wanted to make a kite. I took some brown paper from the tool shed to make it, but got a 'good hiding' for my trouble.

George also got the same for breaking the wheelbarrow. We were good most of the time though. We also kept two pigs which had to be cleaned out. We had out own Bonfire Night in the orchard. We also had some fireworks. Quite good for those days.

At Christmas Father Christmas came with presents. Sometimes I got a girl's present by mistake. Matron told us to sing a carol when we saw him coming.

If any of us were ill we either went to Banbury hospital or if it was something like Scarlet Fever, they used to tape up the doors where children were ill, and fumigate everywhere else.

We only had oil lamps for light.

One May Day I was made 'May King'. I wanted Gwen to be 'May Queen'. But they made Enid Queen instead. I was very disappointed - I liked Gwen very much.

Dinners were good. We had rice pudding, spotted dick and semolina pudding. We had figs and prunes and custard for Sunday tea.

We all had quite a good life at Horley Home. Things could have been much worse. At fourteen you had to leave. The boys generally went as labourers on farms and the girls worked in houses, (in service). When the day came for you to leave they gave you a suitcase with all the clothes you needed for your work. When I left I went to work at a farm in Byfield and was paid two shillings a week for six to seven days work.

Over the years I worked on several farms in the area, but eventually volunteered to join the RAF during the second world war. After I came out I went back to farming, although if there was no work, you lost your house as it was a 'tied' cottage, and belonged to the farmer.

I still love to work in my garden, and other peoples. I still ride my bike (I never did learn to drive). I have many happy memories of Horley Home, which will stay will me forever.

George remembers going to the local pub for carpentry lessons. He also worked on a farm when he left at fourteen, but joined the army towards the end of the war, and was picked out to drive a Brigadier around in Germany. He continued driving for most of his working life, for Midland Red buses, Alcan and Andys Transport.

The girls had a slightly different view. Eileen was was only 4 years old when they went to live in the home. She remembers:

We wore a grey pinafore dress, and our hair was kept short.

We had to clean the dormitory and make our beds.

When Eileen came out of the home at fourteen she didn't even know she had brothers and a sister, although she eventually found out. Eileen worked in the Women's Land Army when she left the home.

Enid's memory was that life was very strictly organised, but they were well fed and looked after. She also remembers the home having two orchards. One was for the home, and the other for market. Fruit was often scrumped from both. She remembers Shadbolts sweet shop — her favourites being sherbert 'dabs' with licorice, and big gobstoppers that they used to pass around, after sucking off one colour. Many years later, when Enid moved north with her new husband, she worked in a sweet factory — it must have been heaven!

Staff

Inmates

Records

Note: many repositories impose a closure period of up to 100 years for records identifying individuals. Before travelling a long distance, always check that the records you want to consult will be available.

- Oxfordshire History Centre, St Luke's Church, Temple Road, Cowley, Oxford OX4 2EX. Holdings include: Medical Certificates (1888-90); Guardians' minute books (1839-1930); House Management Committee minutes 1904-1920; Institution Committee minutes (1920-30); Boarding-out committee minutes (1910-30); etc.

Bibliography

- Victoria County History of Oxford 1954, OUP.

- Potts, William A History of Banbury 2nd Ed. 1978, Gulliver Press 1978.

- The Other Oxford by Charles Fenby (Lund-Humphries, 1970)

Links

- Oxfordshire History Centre, St Luke's Church, Temple Road, Cowley, Oxford OX4 2EX.

Thanks

- Thanks to Christine Upton for kindly contributing information on the Horley Home and the recollections of her uncles and aunts.

Unless otherwise indicated, this page () is copyright Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.