Tramps and Vagrants

Up to 1834

The "houseless poor" — variously known as vagrants, tramps, rogues, vagabonds, and travellers, have always lived on the edge of society often the subject of distrust. They were also regularly the target of legislation — as early as the seventh century a law was framed to make those who entertained travellers responsible for any misdemeanours they committed.

In the fourteenth century, in the aftermath of the Black Death (1348-9), when labour was in short supply and wages were rising steeply, several Acts were passed aimed at forcing all able-bodied men to work and keeping wages at their old levels. These measures led to labourers roaming around the country looking for areas where the wages were high and where the labour laws were not too strictly enforced. Some also took to begging under the pretence of being ill or crippled. In 1349, the Ordinance of Labourers prohibited private individuals from giving relief to able-bodied beggars. In 1388, the Statute of Cambridge introduced regulations restricting the movements of all labourers and beggars. Labourers wishing to move out of their own county "Hundred" needed a letter of authority from the "good man of the Hundred" — the local Justice of the Peace — or risked being put in the stocks.

A century later, in 1494, the Vagabonds and Beggars Act determined that: "Vagabonds, idle and suspected persons shall be set in the stocks for three days and three nights and have none other sustenance but bread and water and then shall be put out of Town. Every beggar suitable to work shall resort to the Hundred where he last dwelled, is best known, or was born and there remain upon the pain aforesaid." Worse was to come — the Statute of Legal Settlement in 1547 enacted that a "sturdy beggar" could be whipped and branded through the right ear with a hot iron, or made a slave for two years — or for life if he absconded. The Act condemned "...foolish pity and mercy" for vagrants. An Act of 1564 aimed to suppress the "roaming beggar" by empowering parish officers to "appoint meet and convenient places for the habitations and abidings" of such classes — one of the first references to what was subsequently to evolve into the workhouse.

In 1597, an Act for the Repression of Vagrancy required than anyone deemed to be a rogue, vagabond, or sturdy beggar, who was found begging could be "stripped naked from the middle upwards and openly whipped until his or her body be bloody, and then passed to his or her birthplace or last residence. Those falling within the scope of this Act included:

- wandering scholars seeking alms

- shipwrecked seamen

- idle persons using subtle craft in games or in fortune-telling

- pretended proctors, procurers or gatherers of alms for institutions

- fencers, bearwards, common players or minstrels

- jugglers, tinkers, pedlars and petty chapmen

- able-bodied wandering persons and labourers without means refusing to work for current rates of wages

- discharged prisoners

- wanderers pretending losses by fire

- Egyptians or gypsies

Over the next two centuries, this list was amended periodically to include any class of person now considered undesirable such as "end-gatherers" (persons buying ends of cloth), poachers, unlicensed lottery ticket dealers, persons "in possession of burglarious implements", and so on.

The Settlement Act of 1662 made wandering an offence and gave magistrates the power to order the removal of travellers back to their place of settlement. The Act also authorized the arrest of rogues, vagrants, sturdy beggars, or idle or disorderly persons, and their committal to a workhouses or House of Correction (an early form of prison), or transportation for seven years to English plantations.

In the eighteenth century, the troublesome business of detaining, maintaining, and conveying vagrants in a county, was often handed over to a paid contractor or "farmer" along similar lines to that employed by parishes for farming their poor. The contractor would receive an agreed amount for each vagrant he maintained (for a maximum of say three days) and for each that was conveyed to the county borders.

During the same period, an informal system grew up of magistrates issuing passes which would allow the bearer to travel unmolested to a named destination and in cases to request a night's board or a few pence for a day's subsistence from an overseer or churchwarden. However, the pass system was widely abused and was in fact increasing vagrancy rather than reducing it. By 1821, a Parliamentary Select Committee estimated that around 60,000 people were perpetually circulating around the country at the public's expense. The Committee concluded that the pass system "has been found to be one of inefficiency, cozenage and fraud."

A new Vagrancy Act followed in 1824 which dictated that every "every Petty Chapman or Pedlar wandering abroad and trading, without being duly licensed... and every Person wandering abroad, or placing himself or herself in any public Place, Street, Highway, Court or Passage, to beg or gather Alms, or causing or procuring or encouraging any Child or Children so to do, shall be deemed an idle and disorderly Person" and liable to imprisonment and a month's hard labour. In addition, every person "wandering abroad and lodging in any Barn or Outhouse, or in any deserted or unoccupied Building, or in the open Air, or under a Tent, or in any Cart or Waggon, not having any visible Means of Subsistence, and not giving a Good Account of himself or herself... shall be deemed a Rogue and Vagabond" and liable to up to three months hard labour. Exceptions could made for discharged prisoners to beg their way home, and for soldiers, sailors, marines and their wives to beg. Natives of Scotland, Ireland and the Channel Islands were also allowed to pass without punishment as these places had no formal system of settlement to which such persons could be legally removed. As a result, habitual vagrants could simply declare themselves to be from Dublin or Glasgow or Jersey and thus remain on the road.

After 1834

The Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834 made no mention of vagrants, with the result of new union workhouses making no provision for them, and Boards of Guardians regarding vagrancy as a matter for the police rather than the poor law. The settlement laws, too, still operated so that a union was obliged to offer relief only to those holding legal settlement within its boundaries. However, tramps continued to claim relief at union workhouses which, it turned out, were usually located within a day's walk of one another. Several instances of tramps dying from exposure or starvation after being turned away from the workhouse door resulted in the Poor Law Commissioners having to compromise. In 1837, a new regulation was introduced which required food and a night's shelter to be given to any destitute person in case of "sudden or urgent necessity" in return them performing a task of work.

This change of heart led to accommodation for vagrants becoming a standard feature of workhouses. At first, this was often provided in existing infectious wards which were often separated from the main workhouse and recognised that tramps often carried contagious diseases such as measles. Gradually, however, purpose-built blocks were added, usually of a single storey and located near the workhouse entrance. They were designed to provide the most basic level of accommodation, inferior to that in the main workhouse. One observer in 1840 reported that they were:

These quarters were known by various names such as tramp wards, vagrant wards, or casual wards — with their occupants officially referred to as the "casual poor", or just as "casuals". Another term that became popular for the tramps' block was "the spike" — a name whose origins are much debated with the most popular being:

- The "spiky" nature of the beds

- A derivation of "spiniken", another tramps' name for a workhouse, originally based on "spinning house".

- A small metal nail sometimes used to help in the task of oakum picking.

- A metal spike on which admission tickets (issued in some areas at local police stations) were placed after being handed over to the workhouse porter

- The spike or finial that often crowned a workhouse roof.

The Casual Ward

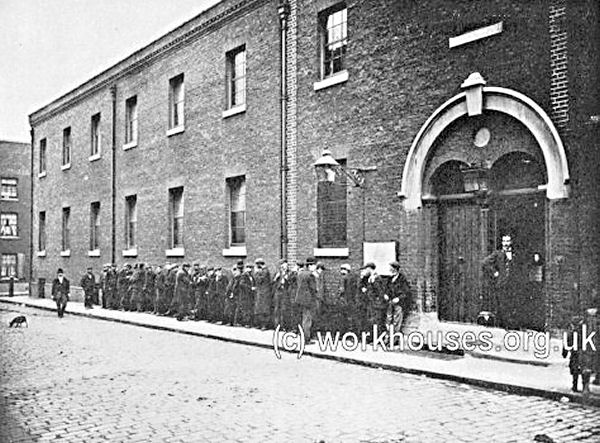

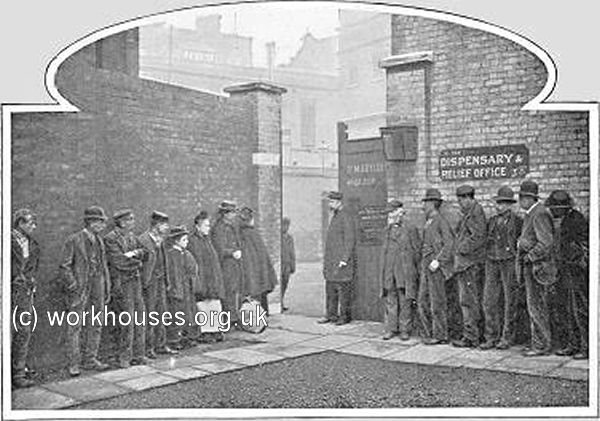

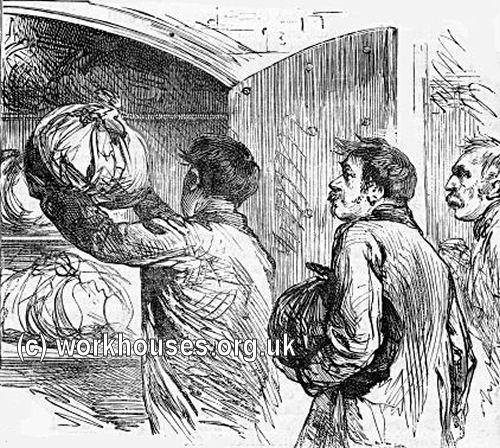

The routine for those entering a casual ward began in late afternoon by joining the queue for admission. A spike had only a certain number of beds and late-comers might find themselves turned away.

Applicants for Admission to a Casual Ward, 1874.

© Peter Higginbotham.

A London Casual Ward - waiting for admission, 1887.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Casuals waiting at entrance to Whitechapel's Thomas Street casual ward, 1902.

© Peter Higginbotham.

St Marylebone casuals' entrance, c.1900

© Peter Higginbotham.

A spike could be staffed in a variety of ways. Sometimes the duties could be combined with that of the workhouse porter, with his wife supervising the female casuals. Some spikes were in the charge of a "Tramp Major", probably a former tramp himself, and now employed by the workhouse.

Advertisement for a porter and tramps' attendant, 1873.

© Peter Higginbotham.

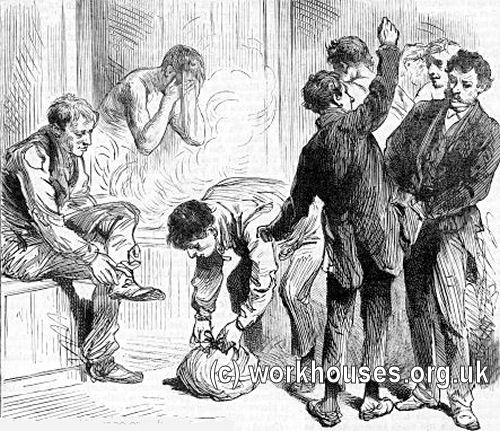

When the spike opened at 5 or 6 o'clock in the evening, the new arrivals would be searched and any money, tobacco or alcohol confiscated. It was common practice for vagrants to hide such possessions in a nearby hedge before entering the spike. According to George Orwell's account of a visit to a spike (possibly the one at Godstone) reveals that it was an unspoken rule that searches never went below the knee so that illicit goods could be hidden in the boots or stuffed into the bottoms of trouser legs. Entrants then had to strip and bathe in water that may already been used by a number of others. They were then issued with a blanket and a workhouse nightshirt to wear while their own clothes being fumigated, dried, and stored. Each was then given a supper, typically 8 ounces of bread and a pint of gruel (or "skilly" as it was colloquially known), before being locked up for the night from 7 p.m. until 6 or 7 a.m. the next morning.

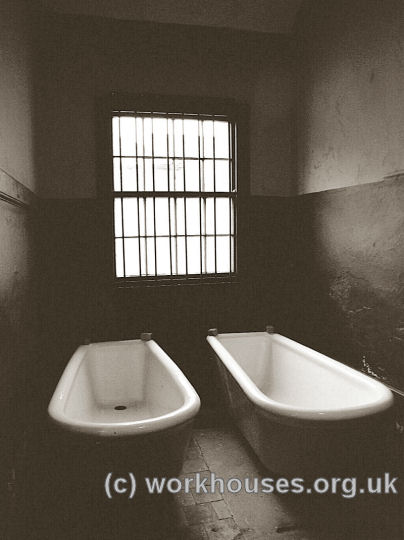

A London Casual Ward - the bathroom, 1887.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Ripon casuals' baths, 2000

© Peter Higginbotham,

courtesy of Ripon Workhouse Museum and Garden, Sharow View, Allhallowgate, Ripon HG4 1LE.

A London Casual Ward - the disinfecting room, 1887.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Vagrants' drying room, Sheffield.

Courtesy of Northern General Hospital Archive, Sheffield.

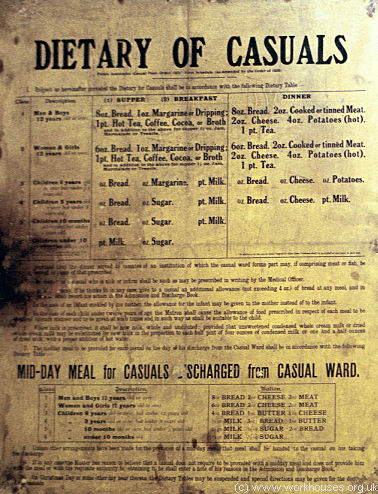

A casual dietary poster, early 1900s

© Peter Higginbotham.

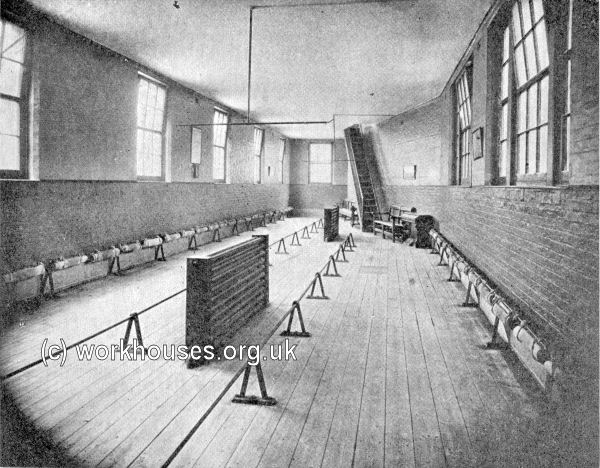

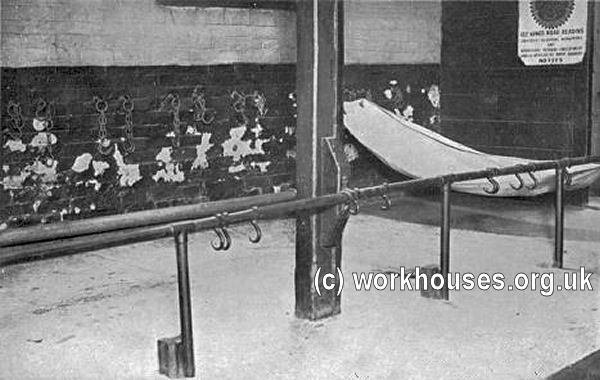

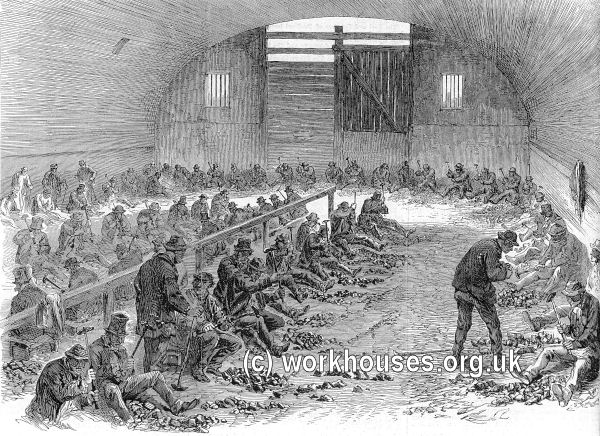

Until the 1860s, the norm was for casual wards to have communal dormitories where the inmates either slept in rows of low-slung hammocks or on the bare floor.

Dormitory of Whitechapel's Thomas Street Casual Wards, c.1902.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Interior of a casual ward, 1920s.

© Peter Higginbotham.

New Casual Ward Designs

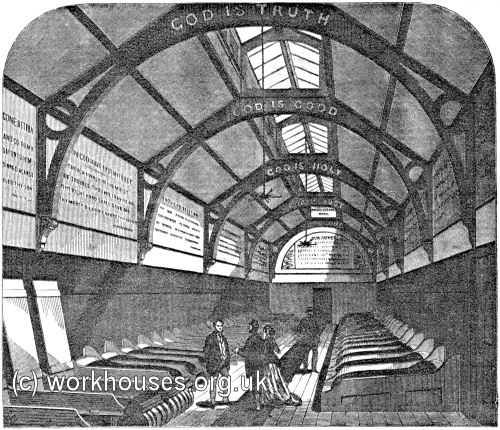

In 1864, the Metropolitan Houseless Poor Act introduced new guidelines for the facilities to be provided in casual wards in the capital. Separate wards were to be provided for men and for women and children, each having a yard with a bathroom and water-closet, and a work shed. It was also recommended that wards have raised sleeping platforms, divided down the middle by a gangway, and each side divided up by boards to give a sleeping space of at least two feet three inches. A narrow shelf along each side of the room provided a shelf at the head of each compartment where clothes could be placed. Bedding was to consist of coarse "straw or cocoa fibre in a loose tick", and a rug "sufficient for warmth". A temporary casual ward, designed by Henry Saxon Snell and clearly based on these recommendations, was erected at St Marylebone workhouse in 1867. Its walls were heavily decorated with religious texts no doubt designed to "improve" the buildings occupants.

St Marylebone workhouse casual ward, 1867.

© Peter Higginbotham.

A detailed description of the building was given in the Illustrated London News.

The Marylebone Workhouse being in every respect a good example to the other London workhouses, we give an illustration of the new building in connection with it, which was opened last week for the accommodation of tramps or casual poor; about 11,000 of whom, men, women, and children obtained relief in the last six winter months. They are washed with plenty of hot and cold water and soap, and receive six ounces of bread and a pint of gruel for supper; after which, their clothes being taken to be cleaned and fumigated, they are furnished with warm woollen I night-shirts and sent to bed. Prayers are read by Scripture-readers; strict order and silence are maintained all night in the dormitory; and the "Amateur Casual" would find nothing to complain of. The bed consists of a mattress stuffed with coir, a flock pillow, and a pair of rugs, At six o'clock in the morning in summer, and at seven in winter, they are aroused and ordered to work. The women are set to clean the wards, or to pick oakum; the men to break stones, but none are detained longer than four hours after their breakfast which is of the same kind and quantity as their supper. Their clothes, disinfected and freed of vermin, being restored to them in the morning, those who choose to mend their ragged garments are supplied with needles, thread, and patches of cloth for that purpose. If any are ill, the medical officer of the workhouse attends to them; if too ill to travel, they are admitted into the infirmary.

The entrance is through the passage leading to the relief offices. At the end of this passage is a general waiting-room, with another for females only, next to which is the female bath-room. The bath-room is 12ft. long, 9ft. wide, 18ft. high. There are two baths, made of Stourbridge clay, having a white glazed surface. The water is heated by a stove in the same room, under the management of the attendant, the cistern holding a hundred gallons of hot water for the two baths. Adjoining this bathroom is the female sleeping-ward, 58ft. long, 18ft. wide, 15ft. high to the lowest part of the sloping edge of the roof, and 22ft. high to the apex. Running along the whole length of the room is a ventilator 5ft. wide. The sides of the ventilator open and close; the top, being glazed, affords light. On the floor immediately beneath is a cast-iron grating covering a brick air-channel which is supplied with fresh air from the outside by covered channels under the floors. It also contains the hot-water pipes for heating the apartment in cold weather. The room is well lighted at night by two pendent star-burners. Ranged down each side of the apartment are the sleeping-bunks for forty-four women and twenty children. These bunks are generally 6 ft. 6 in, long and 2 ft. 4 in. wide, but some are made wider to afford accommodation for a woman and two children each, The bunks consist of a white deal board, supported on each side by a deal partition which rises high enough to prevent the intermingling of the breaths of the occupants of two adjoining berths, though not so high as to prevent the officials in attendance from seeing each person from any portion of the room. The boards forming the beds are so hung on pivots as to be capable of being turned up every day for the purpose of cleaning the floor beneath. The head of the bed under the pillow is slightly raised, and hinged separately, for the purpose of lifting and depositing the clothes of the sleeper; the clothes of each inmate being thus under her own protection. One feature in this ward is the Scripture texts, the Lord's Prayer and the Ten Commandments, printed on the walls and ceiling, in red letters on a blue ground.

The arrangements for the accommodation of the males are identical with that described for the females, except that the bath-room stove is so modified as to allow the smoke and heat to pass by an iron flue through an adjacent disinfecting chamber. If on examination it be found requisite, the clothes of the casual are, whether male or female, hung up in this heated chamber, and well fumigated with sulphur.

On each side of the main building are ranged the working sheds, where the casual in the morning picks oakum or performs such other tasks as may be assigned to him. These sheds are about 12ft. wide and 9ft. high, and are well lighted and ventilated by skylights.

Work in the Spike

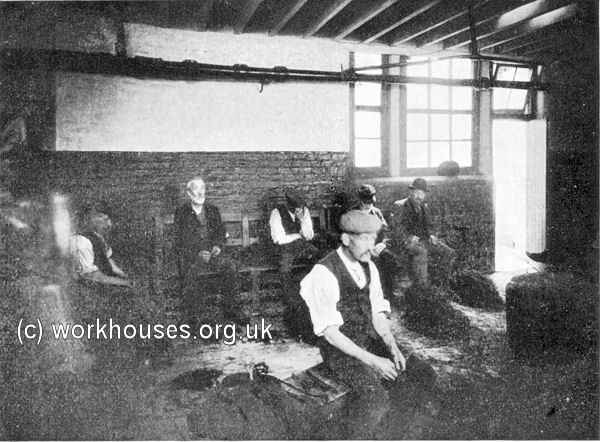

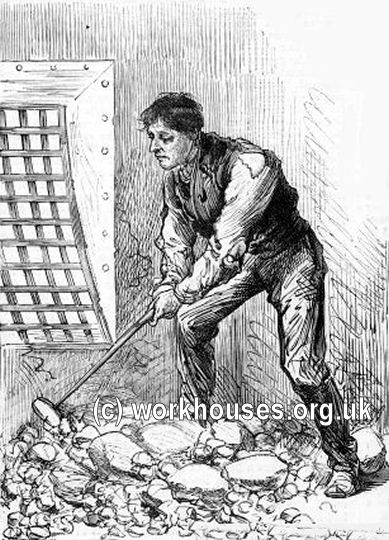

In 1843, workhouses had been given the power to detain male tramps for up to four hours while they performed the required task of work. One common work task was oakum picking where a certain weight (usually one or two pounds) of old rope had to be unpicked into its constituent fibres — the resulting product could then be sold off (hence the expression "money for old rope"!).

Men picking oakum at Whitechapel Casual Ward, 1902.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Women picking oakum, c.1906.

© Peter Higginbotham.

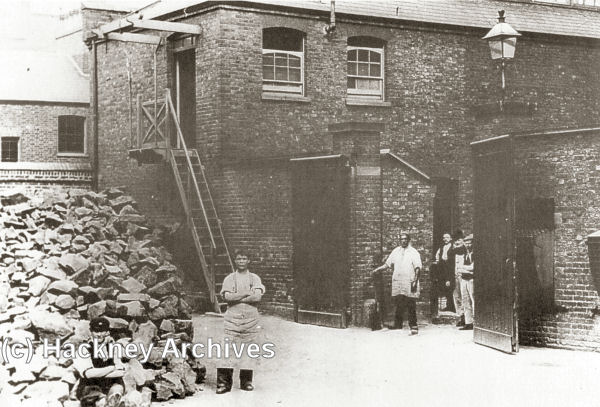

Stone-breaking was another task favoured by Boards of Guardians. Note only was it hard work, but the amount broken (typically two hundredweight) was easily measured, and the resulting small stones could be sold off for road-making.

A stone-breaking yard at Bethnal Green, 1868.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Hackney workhouse stone yard c.1900

© London Borough of Hackney Archives Dept.

Stone-breaking yard at Pontefract.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Stone-breaking cell interior, c.1909.

© Peter Higginbotham.

For female casual, the work given could also include oakum-picking but was often washing, scrubbing or cleaning.

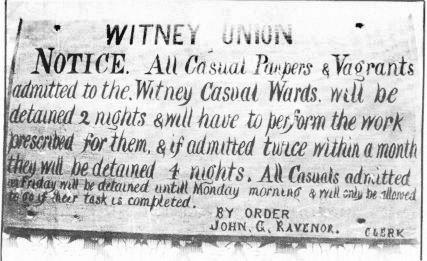

Once vagrants had done their stint of work, they were given a lump of bread and released to go on their way. However, even with an early start to the work, this meant that only half the day remained to tramp to another workhouse. The Casual Poor Act of 1882 made it a requirement for casuals to be detained for two nights, with the full day in between spent performing work. The casuals could then be released at 9 a.m. in the morning after the second night. Return to the same spike was not allowed within 30 days with the penalty being four nights detention with three days work being performed in between.

A warning to vagrants at Witney workhouse.

Courtesy of Newsquest (Oxfordshire) Ltd.

To avoid this penalty, tramping circuits evolved linking a long progression of spikes before eventually returning to the first. Nights at a spike might interspersed with sleeping rough or in farm outhouses, especially in the summer months.

Those entering the casual ward on a Saturday evening were detained an extra day since no work was performed on Sunday. George Orwell's account of a Spike describes a desultory Sunday where the inmates were locked up for the day:

In 1890 William Booth, founder of the Salvation Army, published his book In Darkest England and the Way Out which included some experiences of London casual wards:

The Cellular System

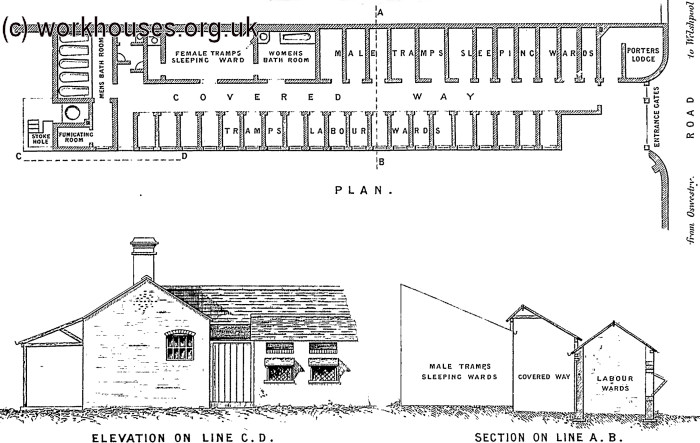

From thr late 1860s, a new form of vagrants' accommodation began to be adopted, its origin attributed to George Fulcher, the master of the Oswestry workhouse, which erected its new casual ward in 1868-9. It consisted of individual cells, very much like those in a prison, arranged along both sides of a corridor. Sleeping cells contained a simple bed, perhaps hinged so that it could be folded up against the wall when not in use. Work cells were fitted out for stone-breaking, typically with a hinged metal grille which could be opened from the outside to allow unbroken lumps of stone to be deposited in the cell. The inmate then had to break up the stone into lumps small enough to pass back through the holes in the grille, or in a separate horizontal grid fitted beneath it. The broken stone could then be collected on the outside. There were variations in the design of stone-breaking cells — some had a bench on which the stone was broken, in others the work was done on the floor. Some designs had separate windows and grilles, while others used the grille itself as a glassless and very draughty window. Sometimes sleeping cells and work cells were separated, sometimes one led through to the other.

The design of the Oswestry vagrants' ward is shown below.

Oswestry vagrants' ward design, c.1868.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The idea was soon taken up by the prolific London architect Henry Saxon Snell, who in 1870 designed a new casual ward for the St Olave's union's workhouse on Lower Street, Rotherhithe. Its design combined sleeping and work into two sections of the same cell. He quickly followed with designs for the St George's and St Marylebone.

In 1874, the Local Government Board recommended the adoption of the cellular principle as the preferred design for casual cells.

Ripon casuals' sleeping cells, 2000

© Peter Higginbotham,

courtesy of Ripon Workhouse Museum and Garden, Sharow View, Allhallowgate, Ripon HG4 1LE.

A stone-breaking cell, 1887.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The similarity with prison cells was often heightened by the inclusion of a "peep-hole" in the door.

Melton Mowbray vagrants' cell peep-hole, 2005.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Cells could also be fitted with bell-pulls in case of a night-time emergency.

Melton Mowbray vagrants' cell alarm bell-pull, 2005.

© Peter Higginbotham.

In April 1880, new casual wards were opened at Salford which adopted the cellular design, as reported in the Local Government Chronicle:

New casual wards, on the cellular system, have been opened this week at the above union workhouse, from designs by Mr. H. Pinchbeck, King-street, Manchester. These wards are the fourth built on the cellular system, and are each fitted with a wood bed, well lighted and ventilated. The doors are strong, and secured with a double lock on the outside. Food doors are inserted, and inspection slides, which enable the attendant to see every portion of the cell without opening the door. To each is fixed a label apparatus, and by turning a handle from the inside a label is thrown out, and the gong placed in the corridor of the administrative department is struck, calling the attention of the attendant, and indicating the cell where he is required. On one side of the building, running the full length, are three rooms, in which mills will be placed for grinding corn, with connecting rods and handles fixed inside the cells, which the vagrants will have to turn and grind a given quantity of corn before leaving the building. On the first floor are the women's cells, eighteen in number, seven being double, for women with children, approached by a wide flight of stone steps, with waiting, bath, and storerooms, and fitted in every respect like the male wards. All the cells throughout are lighted by windows and by gas brackets made purposely, fixed in the corridor, apertures being left in the walls, covered with fine wire, through which the gaslight is admitted. All the cell windows have been designed to open and close simultaneously from the corridor by the attendant, and under his control only. All the floors, except in the administrative department, are laid with cement concrete. Great care has been taken in thoroughly ventilating the cells and other parts of the building, and the whole building is heated by hot water. The contract price for the whole of the works being £4,840. The building stands on a sloping site, and advantage is taken of this to arrange the basement above the outside ground line. This contains heating cellar, coal cellar, stone rooms, cooking kitchen, disinfecting room, and three work-rooms under the cells, each 45 feet long and 24 feet wide. There are three entrances, that in the centre being for the attendant in charge of the building. The entrance on the left is for male and that on the right for female vagrants. The male vagrants enter a spacious corridor, and pass into a waiting-room 21 feet long and 14 feet wide, thence to the bath-rooms, which are directly opposite. There are two, each containing two baths, and fitted with wash-basins, supplied with hot and cold water. Adjoining the waiting-rooms and opposite the bath-room is a large store-room, where rugs and clothing will be kept. On leaving the bath-rooms, the vagrants pass into the cells. There are 36 for males, which are arranged on each side of a corridor 125 feet in length. The building has been designed with a certain degree of taste. The front and side elevations of the administrative department are faced with bright red stocks, relieved with ornamental bands, and the doors, windows, and porches have stone dressings.

A large casual ward of the cellular type was erected in 1893 at Guildford. The building is a rare surviving example of its type and is now being preserved, with a part housing a museum.

Guildford casual ward from the south, 2005.

© Peter Higginbotham

Guildford casual ward corridor in male section, 2005.

© Peter Higginbotham

Guildford casual ward sleeping cell, 2005.

© Peter Higginbotham

Guildford casual ward stone breaking cell, 2005.

© Peter Higginbotham

Guildford casual ward stone-breaking cells exterior, 2005.

© Peter Higginbotham

Numerous variations on the cellular design were erected.

Frome casuals' block from the south, 2000.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Stratford-on-Avon casual ward stone-breaking cells exterior, 2005.

© Peter Higginbotham

Windsor stone-breaking cells, 2000.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Melksham casuals' block, 2000.

© Peter Higginbotham.

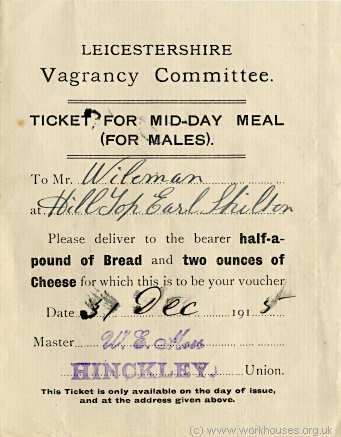

Way Tickets and Bread Tickets

Over the years, the overall numbers admitted to casual wards rose and fell due to a variety of factors. In the "Hungry Forties", trade recessions coupled with the effects of the Irish Famine led to a sharp increase. In 1848, in an attempt to reverse this rise, the Poor Law Board's first President, Charles Buller, issued new guidelines for the admission of casuals. The so-called Buller memorandum urged unions to discriminate between the honest unemployed "temporarily and unavoidably in distress" who were in search of work, and the "habitual tramp or vagrant who simulates destitution". It was suggested that the former category be issued with a certificate, as in the old "pass" system, through which they might receive preferential admission or treatment at the workhouses along a particular route, while the latter might even be refused admission completely unless in immediate danger of starvation. In making this distinction, Buller suggested that local police officers be appointed as assistant relieving officers and take on the job of issuing casual ward admission tickets. In an overenthusiastic response to these proposals, some unions even went so far as close their casual wards. Overall, a 38% drop in casual ward admissions took place in the following year.

By 1863, it had become apparent that many unions were evading their responsibilities towards the casual poor. Poor Law Board President C.P. Villiers issued a circular reminding unions of their obligation to help the genuinely destitute. In London, this was encouraged by making the cost of casual relief chargeable to a common fund, provided for by the Metropolitan Board of Works then, from 1867, by the Common Poor Fund. The resulting resurgence of numbers applying for admission to the casual wards led to the re-introduction of certificates, or way-tickets, in order to identify honest wayfarers. Way-tickets, issued by the police or casual-ward superintendent, were for a specified duration along a particular route and would be endorsed at each workhouse visited. The ticket-holder would be entitled to favourable treatment, such as being exempt from work tasks or being allowed early release from the casual ward. Despite some initial enthusiasm, take-up of the scheme was uneven and its use declined. However, in the early 1900s, a revival of interest took place, helped by encouragement from the Local Government Board, and the creation of County Vagrancy Committees. By 1920, wayticket schemes were operating in 45 counties in England and Wales.

In conjunction with waytickets, many casual wards also issued vagrants with meal-tickets or bread-tickets which could be redeemed for food at a specific location en route. These were intended to try and ensure that casuals kept to their supposed destination, and also aimed to reduce begging.

Bread ticket issued by Hinckley Union, 1915.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The Metropolitan Asylums Board

In April 1912, the Metropolitan Asylums Board (MAB) took over the provision of relief for the capital's casual poor which, according to the 1910 census, numbered over 25,000. The then twenty-eight casual wards in the capital were reduced, falling to six by 1921. However, a rise in demand during the 1920s led to an increase in provision. By 1929, nine were in operation (Chelsea, Hackney, Lambeth, Paddington, Poplar, St Pancras, Southwark, Wandsworth and Woolwich).

The MAB also operated a Night Office under Charing Cross Railway bridge which acted as a clearing house for vagrants. As well as passing people on to its own casual wards, some were referred people to other voluntary agencies. In 1923, the Holborn casual ward was converted to The Hostel where selected cases were given help to obtain employment.

A separate page gives further information on the MAB Casual Wards.

After 1930

Following the abolition of the workhouse system in 1930, the administration of poor relief passed to local county or metropolitan borough councils and their Public Assistance Committees. Although many former workhouse sites were sold off and converted to other uses, or completely redeveloped, many continued in operation (often with very little change) as Public Assistance Institutions. Many casual wards were closed, while those that remained being redesignated as Wayfarers' Reception Centres. In some areas a policy of "canalisation" was adopted, with smaller casual wards being closed and vagrants channelled to particular routes. Some Wayfarer's Reception Centres continued in use until the 1960s.

Social Explorers

Life in the "underworld" presented a particular fascination for the Victorian middle classes and lurid "inside" descriptions of institutions such as the workhouse and spike proved highly popular. These were often compiled by so-called social explorers disguising themselves as down-and-outs to obtain admission to such places as the casual ward. Such investigations were carried out by people as diverse as a clergyman, an American novelist, a politician, and a "Lady".

One of the earliest and best-known undercover reports was A Night in a Workhouse, published by James Greenwood in 1866 in the Pall Mall Gazette of which his brother was editor. Due to huge amount of interest it aroused, it was later reprinted in pamphlet form.

The cover of A Night in a Workhouse

© Peter Higginbotham

Greenwood's titillating prose described not only the repugnant conditions in the spike, but the characters who entered it such as an old-timer known as "Daddy":

'Come on, there's a dry place to stand on up at this end,' said Daddy, kindly. 'Take off your clothes, tie 'em up in your hank'sher, and I'll lock 'em up till the morning.'

Accordingly, I took off my coat and waistcoat, and was about to tie them together when Daddy cried, 'That ain't enough, I mean everything.'

'Not my shirt, Sir, I suppose?'

'Yes, shirt and all; but there, I'll lend you a shirt,' said Daddy. Whatever you take in of your own will be nailed, you know. You might take in your boots, though—they'd be handy if you happened to want to leave the shed for anything; but don't blame me if you lose 'em.'

The other inmates in the spike were a very rough crowd:

After various raucous forms entertaining themselves, the evening ended with a "swearing club":

Also in 1866, medical reformer JH Stallard published the experiences of 'Ellen Stanley', a working woman he had hired to make undercover visits to four of London's female casual wards. Her account was even more shocking than Greenwood's — here is an extract from her description of a night spent in the Whitechapel casual ward:

In the summer of 1902, the American writer Jack London spent some time incognito in London's East End, staying in doss-houses and casual wards and recording his experiences. Here is account of a night at the Whitechapel workhouse:

I did no more than make a show of splashing some of this dubious liquid at myself, while I hastily brushed it off with a towel wet from the bodies of other men. My equanimity was not restored by seeing the back of one poor wretch a mass of blood from attacks of vermin and retaliatory scratching.

A shirt was handed me—which I could not help but wonder how many other men had worn; and with a couple of blankets under my arm I trudged off to the sleeping apartment. This was a long, narrow room, traversed by two low iron rails. Between these rails were stretched, not hammocks, but pieces of canvas, six feet long and less than two feet wide. These were the beds, and they were six inches apart and about eight inches above the floor. The chief difficulty was that the head was somewhat higher than the feet, which caused the body constantly to slip down. Being slung to the same rails, when one man moved, no matter how slightly, the rest were set rocking; and whenever I dozed somebody was sure to struggle back to the position from which he had slipped, and arouse me again.

Many hours passed before I won to sleep. It was only seven in the evening, and the voices of children, in shrill outcry, playing in the street, continued till nearly midnight. The smell was frightful and sickening, while my imagination broke loose, and my skin crept and crawled till I was nearly frantic. Grunting, groaning, and snoring arose like the sounds emitted by some sea monster, and several times, afflicted by nightmare, one or another, by his shrieks and yells, aroused the lot of us. Toward morning I was awakened by a rat or some similar animal on my breast.

But morning came, with a six o'clock breakfast of bread and skilly, which I gave away; and we were told off to our various tasks. Some were set to scrubbing and cleaning, others to picking oakum, and eight of us were convoyed across the street to the Whitechapel Infirmary, where we were set at scavenger work. This was the method by which we paid for our skilly and canvas, and I, for one, know that I paid in full many times over.

Though we had most revolting tasks to perform, our allotment was considered the best, and the other men deemed themselves lucky in being chosen to perform it.

"Don't touch it, mate, the nurse sez it's deadly," warned my working partner, as I held open a sack into which he was emptying a garbage can.

It came from the sick wards, and I told him that I purposed neither to touch it, nor to allow it to touch me. Nevertheless, I had to carry the sack, and other sacks, down five flights of stairs and empty them in a receptacle where the corruption was speedily sprinkled with strong disinfectant.

At eight o'clock we went down into a cellar under the Infirmary, where tea was brought to us, and the hospital scraps. These were heaped high on a huge platter in an indescribable mess—pieces of bread, chunks of grease and fat pork, the burnt skin from the outside of roasted joints, bones, in short, all the leavings from the fingers and mouths of the sick ones suffering from all manner of diseases. Into this mess the men plunged their hands, digging, pawing, turning over, examining, rejecting, and scrambling for. It wasn't pretty. Pigs couldn't have done worse. But the poor devils were hungry, and they ate ravenously of the swill, and when they could eat no more they bundled what was left into their handkerchiefs and thrust it inside their shirts.

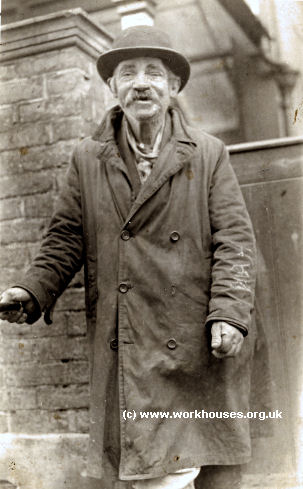

A typical "casual", c.1900.

© Peter Higginbotham.

In 1904, "A Lady" (later revealed to be one Mary Higgs) published an anonymous account of undercover stays in several lodging houses and casual wards. Mary Higgs was born in 1854 at Devizes in Wiltshire, and was the daughter of a Congregational minister William Kingsland. In 1862, the family moved to Bradford where her father became minister at College Chapel. She was educated at a local private school, and at Girton College in Cambridge where she was the first woman to study for the Natural Science Tripos. In 1879, three years after her father's death, she married the Revd. Thomas Kilpin Higgs. She later settled in Oldham and, amongst many other religious and philanthropic activities, became Secretary of the Ladies Committee visiting the Oldham Union workhouse. She became particularly interested in vagrancy reform and determined to discover first-hand what conditions were like in accommodation such as casual wards and common lodging houses. Her experiences revealed the squalid conditions often to be found, and how vulnerable female vagrants could be. Her refined sensibilities were also clearly affronted by the conditions inside such establishments, such as the gruel having no salt in it...

...

Put to bed, like babies, at about half-past six, the kind woman in charge brought us our food. Only one thing had exercised my mind—"What did that pauper mean by my going to him later?" However, I told the portress all about what he said. She was very indignant, and said I must tell the superintendent of the tramp ward next morning, that she had to leave us, but would take good care to lock us in, and I need not be afraid, he could not get. at us. We were very hungry, having had nothing to eat since about twelve o'clock. Anything eatable would be welcome, and we were also thirsty. We were given a small lading-can three parts full of hot gruel and a thick crust of bread. The latter we were quite hungry enough to eat, but when we tasted the gruel it was perfectly saltless. A salt-box on the table, into which many fingers had been dipped was brought us; the old woman said we were "lucky to get that." But we had no spoons; it. was impossible to mix the salt properly into the ocean of nauseous food. I am fond of gruel, and in my hunger and thirst could easily have taken it. if fairly palatable. But I could only cast in a few grains of salt and drink a little to moisten the dry bread : my companion could not stomach it at all, and the old woman, being accustomed to workhouse ways, had a little tea in her pocket, and got the kind attendant to pour the gruel down the w.c. and infuse her tea with hot water from the bath tap. We were then left locked in alone, at eight o'clock, when no more tramps would be admitted. The bath-room, containing our clothes, was locked ; the closet was left unlocked : a pail was also given us for sanitary purposes. We had no means of assuaging the thirst which grew upon us as the night went on; for dry bread, even if washed down with thin gruel, is very provocative of thirst. I no longer wonder that tramps beg twopence for a drink and make for the nearest public-house. Left alone, we could hear outside the voice of the porter. I wondered if he expected us to open a window. However we stayed quiet, but had one " scare." Suddenly a door at the end of the room was unlocked, and a man, put his head in. He only asked, "How many? " and when we answered "Three," he locked us in speedily. I could not, however, get to sleep for a long time after finding that a man had the key of our room, especially as our elderly friend had told us of another workhouse where the portress left the care of the female tramps to a man almost entirely, and she added that "he did what he liked with them." I expressed horror at such a state of things, but she assured me it was so, and warned us not on any account to go into that workhouse.

|

|

In the 1920s, former Oxford MP Frank Gray made undercover visits a number of Oxfordshire casual wards as part of his efforts to save teenage vagrants from a life on the road.

Frank Gray disguised as a tramp.

© Peter Higginbotham.

His stay at Thame was typical:

The gates open; we walk up the garden. A clerk takes particulars under a lamp at the front door, and we pass to the back, isolated from the higher grade of the workhouse, the permanent inmates. We shamble into this workhouse from the outer world, and then past the quarters of the permanent inmates to our den at the back midst the refuse heaps, well-nigh like lepers-the unclean.

I made a slip as I gave my answers, for I noticed the clerk momentarily start as he detected a pitch of voice unusual in a casual ward. I must be more careful thereafter.

In the Thame workhouse there is no strict search; there is no suggestion of a bath or a wash. We retain our clothes and sleep in some of them. To-night I have a pillow - my boots with my trousers wrapped over them. We sleep on boards on a gradient raised from the floor, and the slope helps sleep.

As we arrived at this workhouse and answered the stereotyped questions - as listlessly as they were asked - we received our hunk of bread, and with it we said good-bye to all officialdom and supervision and entered the casual ward. As the tramps have lost heart so have the officials.

Here the casual ward is a long narrow apartment with an overflow department upstairs. In the apartment I am in downstairs there is a sort of ante-room, just big enough for three; it is the antechamber of the lavatory - indeed it is part of the unsavoury arrangement whereby a tramp may wash, if he has not already lost heart and realized that in the general discomfort and squalor cleanliness has lost its meaning and its values.

Here, unclean and unhappy, I lie in a chamber already the home of body vermin and house vermin. With such hospitality as this, what do I owe to society?

Alternatives to the Spike

The casual ward was not the only form of shelter for the destitute or near destitute. Many other types of establishment existed, particularly in large cities such as London, Manchester and Liverpool. Some were privately run, while others were operated by charities and religious organizations. A number of these are described in separate pages on common lodging houses, The Salvation Army, and Rowton Houses.

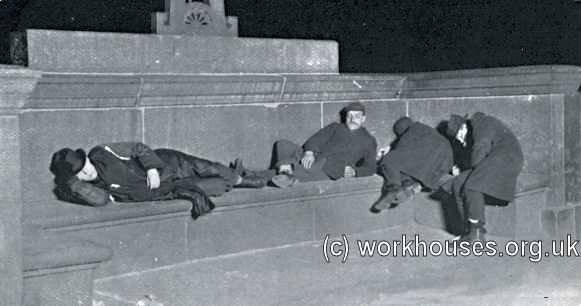

Asleep On Southwark Bridge, c.1900.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The Vagrant Population

Unlike inmates of the main workhouse, relatively little was recorded about inmates of the casual ward. An early snapshot of the vagrant population is provided by a survey of the individuals entering the vagrant ward of the West London union in March 1848. A typical day's entry is shown below:

| Tuesday, March 7, 1848. | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name. | Age. | Married or Single. | No. of Children. | Where from. | Remarks. |

Ann Dawson |

39 |

Widow |

3 |

Essex |

Cadger, been here many times. |

Susan Dawson |

16 |

Single |

.. |

" |

Ditto |

Bridget Brady |

44 |

" |

.. |

Mayo |

Ditto |

Mary Carty |

24 |

" |

.. |

Cork |

Ditto |

Eliza Fannigan |

15 |

" |

.. |

Galway |

Ditto |

Mary Collins |

30 |

" |

.. |

Cork |

Ditto |

Mary Brown |

49 |

Widow |

.. |

Seacole Lane |

Cadger, been here before. |

Margaret Lewis |

32 |

Married |

.. |

Guernsey |

Charwoman, out of employ. |

Ellen Crawley |

29 |

Single |

.. |

Skibbereen |

Cadger, sleeping in different refuges. |

Nancy Crawley |

12 |

" |

.. |

Cork |

Ditto |

Joseph Carter |

19 |

" |

.. |

Chatham |

Cadging on her way home. |

John Harris |

23 |

" |

.. |

Hertford |

Shoemaker, seeking employ. |

Mary Donovan |

23 |

" |

.. |

Cork |

Cadger, sleeping in different refuges. |

Johanna Neil |

33 |

Married |

1 |

" |

Ditto |

Mary Neil |

7 |

. . |

.. |

" |

Ditto |

George Harris |

20 |

Single |

.. |

Shropshire |

Ditto |

Isaac Twithet |

24 |

" |

.. |

Great Berkhamstead |

Labourer, seeking employ. |

George Wood |

17 |

" |

.. |

Sussex |

Cadger, seeking employ. |

Pat Robson |

32 |

" |

.. |

New Castleton |

Travelling draper. |

James Davis |

15 |

" |

.. |

Somersetshire |

Cadger, sleeping in different refuges. |

Maria Hellen |

20 |

" |

.. |

Gosport |

Needle-woman, seeking employ, by P.C.254, 1½ |

Elizabeth Griffiths |

38 |

Married |

.. |

Buckinghamshire |

Servant, out of employ. P.C.260, 2½ |

22 |

GEORGE JERRARD, Porter. |

||||

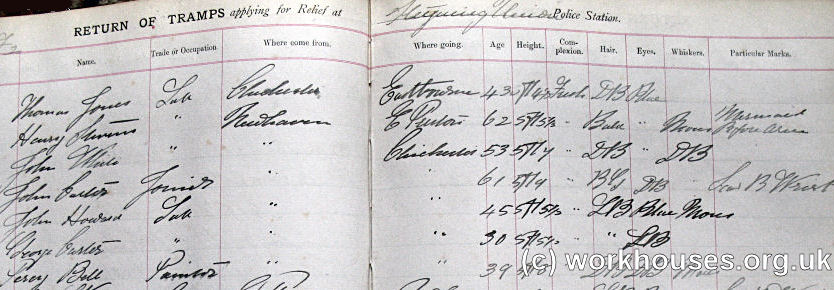

The information recorded about each vagrant generally comprised five basic questions: "Name", "Age", "Occupation", "Where from:", and "Where to". Some brief details of physical appearance might also be recorded as shown in the extract below from the Steyning Union's "Tramp Book" in 1907:

Steyning Union Tramp Book, 1907.

As well as the paucity of information recorded, its reliability is far from certain — vagrants were no doubt sometimes inclined to give false information when responding the questions put to them by officialdom.

Official returns of numbers in casual wards were compiled for January 1st and July 1st each year. The data for the years between 1850 and 1930 are shown in the graph below which also illustrates the overall proportion of the population receiving any kind of poor relief.

Casual totals 1850-1930.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The figures make several interesting points:

- Apart from a dip during the First World War, the numbers of casuals rose steadily between 1850 and 1930. The overall increase was five or sixfold for a period when the national population had roughly doubled.

- The general level of pauperism declined steadily over the same period, indicating that poverty was not the main determining factor of vagrancy.

- Prior to the mid-1880s, the numbers of casuals was generally higher on July 1st than January 1st. In subsequent years, casual totals were higher in January.

- General pauper numbers were consistently higher in January than July.

Women and children formed part of the casual ward population. In 1845, non-metropolitan casual wards received a total of 247,227 males against 39,539 females (Rose, 1988) — women thus forming around 13.8 per cent of the inmates. The proportion declined slowly over the years so that on January 1st 1905, the total number of casual ward inmates in England and Wales was 9,580 of which women made up 9.3 per cent. On that same night in 1905, 188 children were recorded as casual ward residents.

Frank Gray, writing in around 1930, distinguished a number of distinct vagrant "types":

- The "real free, true, and genuine tramp" — possibly the child of tramps, a lover of the countryside, and who loved to roam alone. Gray believed that this type formed quite a small proportion of the tramp population.

- Genuine workers seeking employment — again small in number. Gray argue that the number of this type stayed low since after a few months on the road, the genuine worker invariably lost his identity amongst the ranks of the long-term vagrants.

- Labouring navvies — men employed on a casual basis in the construction of roads, railways etc. These men often resorted to the casual ward between jobs when their money had run out. This type were, Gray reckoned, of generally better appearance than permanent tramps.

- Seafarers — travelling between ports, or between their home and a port.

- Seasonal workers — these took to the road in the spring and summer to reach specific districts for specific purposes. The Irish and others worked out for haymaking and harvesting, while those from town slums left their winter residences to pick fruit, peas, hops etc. In later years the "hoppers" came to form a distinct class who treated the expedition as a holiday jaunt, but sleeping rough or using the casual wards en route.

- Professional beggars — although many types of vagrant begged, the majority begged to live. The professional beggar, on the other hand, lived to beg, and could make a good living at it. Such beggars often had a small stock of goods — lavender, shoe-laces, combs, cotton-reels etc. — which were more used to open a conversation with a likely prospect with a view to begging. In order to evoke sympathy, such men often wore war medals which they were not entitled.

- Habitual drunkards — which Gray considered formed the largest portion of all vagrants. Such men often spiralled downwards — they "beg and drink beer and lose all interest in food, and so in their weakness, as they totter to death, they require less beer to dull their senses."

- Habitual criminals — another large and important class of tramps. These were men who were past their prime as regards active criminal operations but who claimed status on the basis of past exploits and length of sentences served. In their twilight years they often turned their hand to training younger men in the business.

- Physical "degenerates" — those who, usually from birth have suffered physical deformity or incapacity resulting in difficulty in obtaining manual work.

- Mental "degenerates" — those suffering intellectual or personality disorders which had led to their descending into the realms of the casual ward. Gray reported the results of a survey which found that the proportion of casuals who would be classified as "lunatics" was 5.7%.

- Youths — a type in which Gray had a particular interest in helping. These were young men who, through family circumstance, economic conditions, the social disruption of war, or just sheer wanderlust, had joined the numbers frequenting the casual ward but had not graduated to its long-term habitués — though were considerable danger of doing so.

Exactly what proportion of the total was constituted by each of such categories is difficult to assess. Mary Higgs, in her evidence to the Departmental Committee on Vagrancy in 1904, quoted a survey carried out by a Poor Law Official in a northern union where only three percent of casual ward inmates were reckoned to be "habitual vagrants". Separate evidence from the Workhouse Masters Association made a very different claim — that only three percent of casuals were genuinely seeking work.

It also needs to be remembered that those who made use of the casual wards formed only a small part of the nation's wandering homeless. The 1904 Departmental Committee estimated that there was a hard core of up to 30,000 permanent vagrants in England and Wales, of which the casual ward figures accounted for only around twenty per cent.

Many longstanding vagrants often became well-known "characters" in their area, such as Franky Shagg from the Isle of Wight.

Franky Shagg, date unknown.

© Peter Higginbotham.

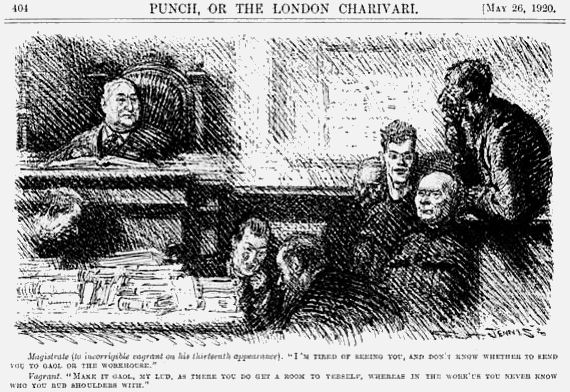

Incorrigible vagrant cartoon, 1920.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Bibliography

- Booth, William (1890) In Darkest England and the Way Out (London: Salvation Army)

- Duncan Cumming (1901) Life In A London Workhouse

- Edwards, Rev. George Z (1910) A Vicar as Vagrant (London: PS King)

- Greenwood, James (1866) A Night in a Workhouse (pamphlet reprinted from Pall Mall Gazette)

- Gray, Frank (1931) The Tramp: his Meaning and Being (Dent, London)

- Higgs, Mary (1904) Five Days and Five Nights as a Tramp Among Tramps — Social Investigation by a Lady

- Higgs, Mary (1904) The Tramp Ward

- London, Jack (1903) The People of the Abyss

- Orwell, George (1931) The Spike

- Rose, Lionel (1988) Rogues and Vagabonds (London: Routledge)

- Stallard, JH (1866) The female Casual and her Lodgings (London: Saunders, Otley & Co.

Links

- The Guildford Spike - a musuem set in the former Guildford workhouse vagrants' block.

- Ripon Workhouse Museum is set in the former vagrants' block of Ripon workhouse.

Unless otherwise indicated, this page () is copyright Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.