Boston Pauper Institutions, Massachusetts, USA

Boston built its first almshouse in 1662 and another in 1686 after the first one burned down. The latter was a large, two-storey building at the junction of Beacon Street and Park Street — across from the Common and the future site of the State House. The cost of its construction was partly financed by subscriptions from wealthy donors. The establishment was intended for 'the relief of the poor, the aged, and those incapacitated for labor; of many persons who would work but have not the wherewithal to employ themselves; of many more persons and families who spend their time in jolliness and tippling, and who suffer their children shamefully their time in the streets, to assist, employ and correct.' Not all paupers were offered the almshouse. Those considered to be of a respectable character could receive outdoor relief in their own homes.

During the period of the Revolution, the town's Overseers of the Poor were forced to plead for loans for the 'poor in the Almshouse, entirely destitute and in immediate danger of perishing for want of the necessities of life.' the inmates, who numbered up to 300, were reduced to begging through the almshouse fence for food from passers-by.

A prison or bridewell was was added to the site in 1723, followed in 1739 by a workhouse which was to accommodate 'idle and vagabond persons, rogues, and tramps.' The workhouse inmates were employed in picking oakum.

By the 1790s, the almshouse and workhouse were both overcrowded and in a poor condition. The increasingly unsightly buildings were also located in what was becoming the fashionable district of Beacon Hill. Accordingly, in 1795, the old site were sold and new buildings erected at Barton's Point, on the north side of Leverett Street, roughly where Martha Road now runs. After a delay due the necessity of building a sea wall for the waterside site, the new almshouse, designed by Charles Bullfinch, was opened in 1800. Although it was larger than its predecessor, the new building — designed for the 'worthy poor' did not provide for the separation of the inmates of the old almshouse and workhouse, all of whom were transferred to the new establishment. Plans for a new workhouse did not materialise. Instead, some outbuildings were converted for the purpose and included a jail, whose twenty-four cells were used 'to limit, to restrain, or punish even the inhabitants of the almshouse.'

The new almshouse was soon greatly overcrowded. Of the 400 inmates in 1812, 300 were aged, invalids, or children, with 20 of that number being insane and 50 needing medical care in the little space assigned for that purpose. As a result, the institution had a high death rate. As had happened at Beacon Hill, the increasing development of area around Barton's Point made the almshouse site increasingly valuable and new premises were erected at a then isolated location in South Boston. Opened in 1822, the House of Industry as it was now known, was accompanied by sixty acres of farmland on which the inmates could work. undeveloped. Originally intended for the reception and employment of the able-bodied poor, the establishment soon became 'a general infirmary — an asylum for the insane, and a refuge for the deserted and most destitute children of the city.' So many of the inmates were sick, insane, old, or 'idiots', most of the labour of the able-bodied was taken up in the care of those who could not take care of themselves.

Author Charles Dickens visited the House of Industry in 1842 and recorded his impressions as follows:

There is the House of Industry. In that branch of it, which is devoted to the reception of old or otherwise helpless paupers, these words are painted on the walls: 'Worthy of Notice. Self-Government, Quietude, and Peace, are Blessings.' It is not assumed and taken for granted that being there they must be evil-disposed and wicked people, before whose vicious eyes it is necessary to flourish threats and harsh restraints. They are met at the very threshold with this mild appeal. All within-doors is very plain and simple, as it ought to be, but arranged with a view to peace and comfort. It costs no more than any other plan of arrangement, but it speaks an amount of consideration for those who are reduced to seek a shelter there, which puts them at once upon their gratitude and good behaviour. Instead of being parcelled out in great, long, rambling wards, where a certain amount of weazen life may mope, and pine, and shiver, all day long, the building is divided into separate rooms, each with its share of light and air. In these, the better kind of paupers live. They have a motive for exertion and becoming pride, in the desire to make these little chambers comfortable and decent.

I do not remember one but it was clean and neat, and had its plant or two upon the window-sill, or row of crockery upon the shelf, or small display of coloured prints upon the whitewashed wall, or, perhaps, its wooden clock behind the door.

The orphans and young children are in an adjoining building separate from this, but a part of the same Institution. Some are such little creatures, that the stairs are of Lilliputian measurement, fitted to their tiny strides. The same consideration for their years and weakness is expressed in their very seats, which are perfect curiosities, and look like articles of furniture for a pauper doll's-house. I can imagine the glee of our Poor Law Commissioners at the notion of these seats having arms and backs; but small spines being of older date than their occupation of the Board-room at Somerset House, I thought even this provision very merciful and kind.

Here again, I was greatly pleased with the inscriptions on the wall, which were scraps of plain morality, easily remembered and understood: such as 'Love one another' — 'God remembers the smallest creature in his creation:' and straightforward advice of that nature. The books and tasks of these smallest of scholars, were adapted, in the same judicious manner, to their childish powers. When we had examined these lessons, four morsels of girls (of whom one was blind) sang a little song, about the merry month of May, which I thought (being extremely dismal) would have suited an English November better. That done, we went to see their sleeping-rooms on the floor above, in which the arrangements were no less excellent and gentle than those we had seen below. And after observing that the teachers were of a class and character well suited to the spirit of the place, I took leave of the infants with a lighter heart than ever I have taken leave of pauper infants yet.

Connected with the House of Industry, there is also an Hospital, which was in the best order, and had, I am glad to say, many beds unoccupied. It had one fault, however, which is common to all American interiors: the presence of the eternal, accursed, suffocating, red-hot demon of a stove, whose breath would blight the purest air under Heaven.

In 1847, a quarantine and poorhouse facility was erected on Deer Island, initially to accommodate the large number of sick Irish immigrants in Boston. The original wooden buildings were replaced in 1851 by a large brick building which was subsequently also used to house the city's criminals and juvenile delinquents.

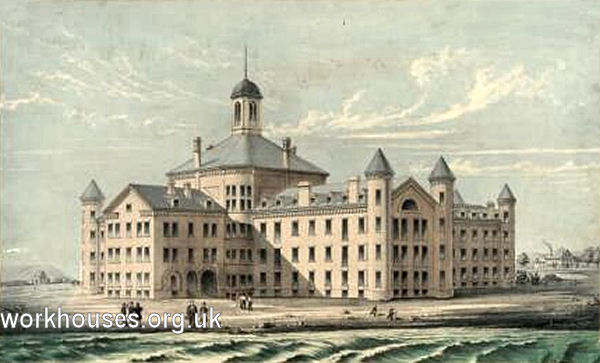

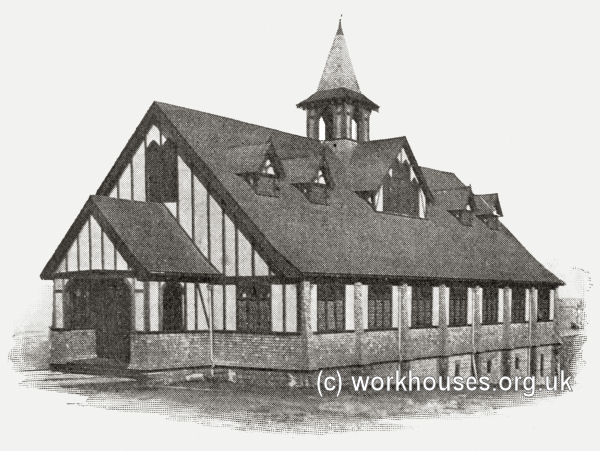

Design for Deer Island Almshouse, Boston, Massachusetts, c.1897.

In 1887, a large brick building was erected on Long Island and the female paupers were brought there from Austin Farm, to where they had been removed from Deer Island ten years earlier. However, within two years of their arrival they were transferred to Rainsford Island, where the male paupers had stayed since leaving Deer Island in 1872, to take the places of the male paupers who in turn took their places at Long Island. The reason for this change was that on Long Island the men could be set to work, while on Rainsford they had little or nothing to do. When the hospital on Long Island was ready for occupancy in 1893, the inmates of the Rainsford Island hospital were removed to it, and on the completion of the women's dormitory building at Long Island, two years later, all the women were brought back.

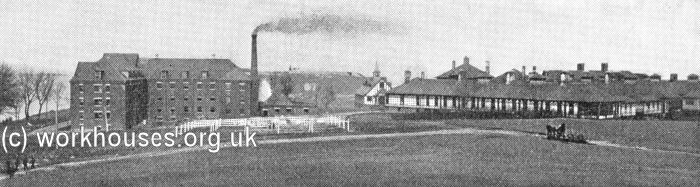

Long Island Almshouse, Boston, Massachusetts, general view from the south east, c.1897.

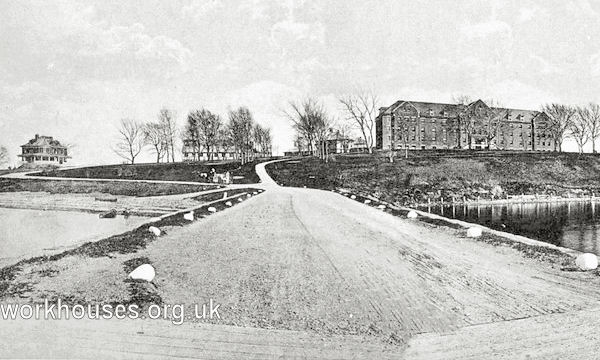

Long Island Almshouse, Boston, Massachusetts, from the west showing (left to right) Superintendent's House, women's dormitory block and chapel, hospital, main building, c.1900.

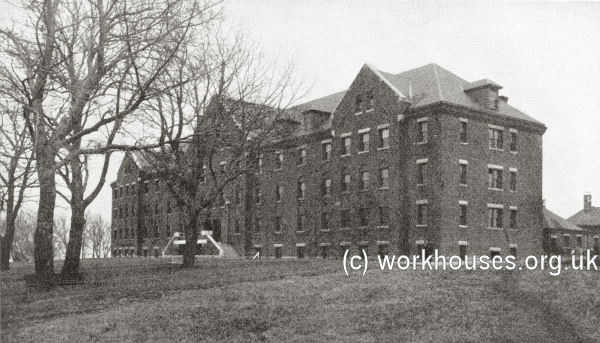

Long Island Almshouse, Boston, Massachusetts, main building from the south, c.1897.

Long Island Almshouse, Boston, Massachusetts, men's dormitory, c.1897.

Long Island Almshouse, Boston, Massachusetts, loafers' room, c.1897.

Long Island Almshouse, Boston, Massachusetts, women's building, c.1897.

Long Island Almshouse, Boston, Massachusetts, sewing room, c.1897.

Long Island Almshouse, Boston, Massachusetts, women's building, c.1897.

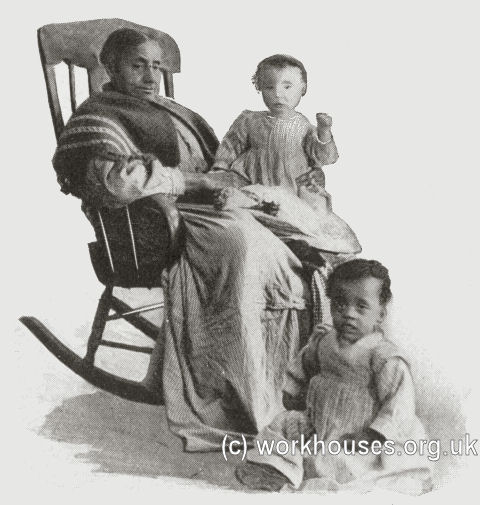

Long Island Almshouse, Boston, Massachusetts, children's ward, c.1897.

Long Island Almshouse, Boston, Massachusetts, hospital building, c.1897.

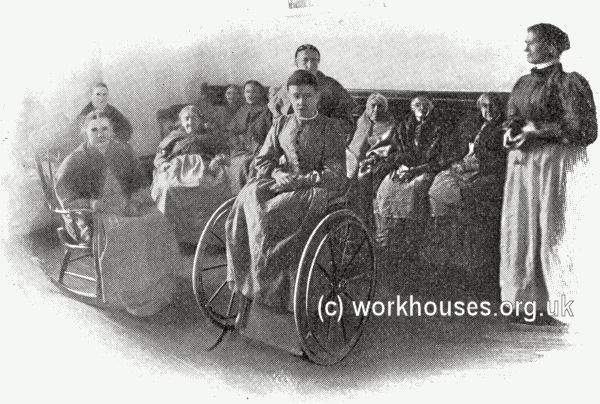

Long Island Almshouse, Boston, Massachusetts, hospital ward, c.1897.

Long Island Almshouse, Boston, Massachusetts, nurses, c.1897.

Long Island Almshouse, Boston, Massachusetts, chapel, c.1897.

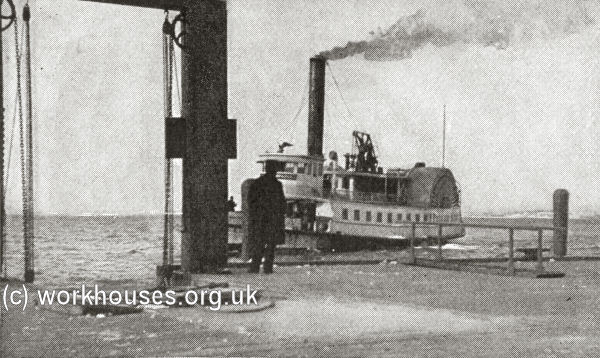

Travel to and from the island was by the paddle steamer J Putnam Bradlee, named after a local businessman and mill owner.

Long Island Almshouse, Boston, Massachusetts, steamer J Putnam Bradlee, c.1897.

Long Island Almshouse, Boston, Massachusetts, landing stage, c.1897.

In 1873, Boston took over the almshouse at Charlestown as an annexe for the Long Island establishment, mainly accommodating pauper couples. With the closure of the Charlestown branch in 1911, its 100 or so inmates were transferred to Long Island where additional inmate were erected to accommodate them.

In 1924, the Long Island Almshouse and Hospital was renamed the Long Island Hospital.

The buildings in the complex were steadily expanded and by the 1930s comprised the superintendent's house, the main institution building, men's and women's dormitories, men's and women's hospital buildings, a chapel, a power house, and a recreation centre known as the Curley building. The land surrounding the hospital was cultivated for both crop and animal production. A separate Hospital for Consumptives was opened in 1902. In 1921, the almshouse was converted into a home for single mothers and in 1928 the a shelter for homeless men was added. In 1941 the hospital created a treatment program for alcoholics which operated for several decades. The hospital is no longer in operation, though the homeless shelter is.

Records

Note: many repositories impose a closure period of up to 100 years for records identifying individuals. Before travelling a long distance, always check that the records you want to consult will be available.

- Massachusetts Historical Society, 1154 Boylston StreetBoston, MA 02215. Boston Overseers of the Poor records (1733-1925) include the Boston Almshouse records (1735-1911), consisting of admission and discharge registers, lists of inmates, deaths, indentures, accounts, and memoranda.

- City of Boston Archives, 201 Rivermoor Street, West Roxbury, MA 02132, USA. Holdings include: Almshouse admission register (1808); Deer Island and Rainsford Island Almshouse admission/discharge registers (1853-1914).

Bibliography

- Meltsner, Heli The Poorhouses of Massachusetts: A Cultural and Architectural History (2014, McFarland).

Links

- None.

Unless otherwise indicated, this page () is copyright Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.