A Visit to Gloucester Workhouse

The text below is a slightly abridged version of an article by Mrs Emma Brewer, published as part of the series 'Workhouse Life in Town and Country', in the magazine Sunday at Home in 1890.

A Visit to Gloucester Workhouse

The Gloucester Workhouse stands practically on the railway, just outside the station.

It is an imposing-looking building of red brick, built in 1836, and the day we were there contained two hundred and thirty inmates, and thirty children.

An infirmary was added in 1860, which appears to us unsatisfactory. For example, the stairs are too steep and twisty, and the passages so narrow that it is impossible to carry a stretcher with a bad case on it up to the wards.

Ten years ago this workhouse was so filthy and neglected that, we are assured, it would have been impossible for us to have gone through it, and now, notwithstanding its proximity to the railway, everything in it and about it is scrupulously clean and orderly. In fact, it is as good a specimen of what ten years have effected in workhouse management as could be seen.

Among the inmates there are many old agricultural labourers, and a large number of factory women, dock labourers and waggon hands, beside many deserted women and women with families — drink being in a great measure the cause of the latter classes finding themselves here.

Beside the master and matron, the paid officers consist of the schoolmaster and mistress, an industrial trainer, a nurse, porter, cook, tramp master and mistress, a tailor and shoemaker. The two last teach their trades to the boys, who not infrequently develop into very good shoemakers, tailors, and gardeners, trades which serve them in good stead both here and in the Colonies, whither many of the boys go after leaving the house.

The children are kept until they are twelve or fourteen, and have passed the fourth standard, which, being the minimum necessary for the wage-earning community, means reading with intelligence, writing clearly and correctly from dictation, and working sums rapidly in the compound rules of arithmetic.

One of the great wants in the workhouse for the girls who have to go out to service has been the industrial training necessary for a small household. Everything is on so large a scale that when they first go out to service they are confused at finding themselves in a small kitchen; for example, they cannot light an ordinary fire, they know nothing of the use of the saucepan or gridiron, they are unable from sheer ignorance of their surroundings to perform the duties of their new position, and they lose heart and often head too, and turn out a failure.

Dr. Clutterbuck, the Poor Law Inspector, has long tried to remedy this, and it must be a pleasure to him, as it was to us, to note that Gloucester has recognised that a workhouse school should be a real practical school of cookery and household training, from whence little kitchen maids, parlour-maids, housemaids, and nurses could go out into the world to better themselves.

It has provided a tiny bright kitchen and scullery outside the girls' day-room, where all this is taught by the industrial trainer. Here, a few weeks ago, one of the girls aged thirteen cooked and served up a nice little dinner, quite unaided, on the occasion of the inspector's visit. He was very pleased, fur this special training has been one of his hobbies.

Another departure from ordinary rules struck us pleasantly, and this was giving the children twice a week bread cake, instead of bread and cheese. It is ordinary bread with currants and a little sugar; it delights the little ones, and is much more wholesome for them than bread and cheese.

We were very pleased with the women's sitting-room, which was exceptionally pretty and cheerful, with its crimson curtains and table covers, its bright pictures and flowers; the women themselves seemed happy, and were occupied with needlework for the house.

Another part of the house which we would gladly have spent some time in was the day-room and little kitchen for the girls. In the former, the girls wore very busy at needlework and knitting, both of which were good and did credit to the industrial trainer, a kind sensible woman. The room was adorned with pictures, and on one side hung a neat row of brush and comb bags, each child having its own. Everything in the little kitchen adjoining was bright as the girls could make it.

The food is good and varied; instead of porridge, the adults have tea and bread and butter, while the children have bread and milk.

The wardswomen and washers are allowed half a pint of beer a day, and the old men over sixty an ounce of tobacco a week. There is accommodation for a married couple, but it is not in demand.

The infirmary is exceedingly well cared for, the wards are bright, and there is a nice little hospital kitchen, where beef tea or any little extra is prepared. There is also a well-supplied surgery. A paid dispenser comes in twice a day for half an hour, and dispenses for three doctors.

The chapel is small but pretty, and well cared for. Service is held twice on Sundays.

The casual wards are on the cell system.

The death rate is very low.

Altogether this workhouse is a credit to the master and matron as well as to the guardians.

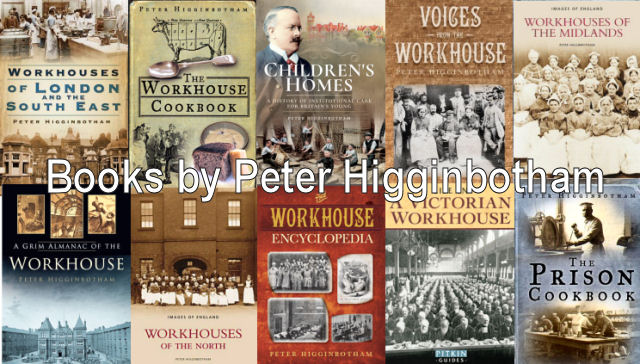

Unless otherwise indicated, this page () is copyright Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.