A Visit to Chelsea Workhouse (1879)

In 1879, a visitor to Chelsea workhouse gave his impressions of the establishment, a slightly shortened version of which is given below.

A VISIT TO CHELSEA WORKHOUSE.

I have been to Chelsea Workhouse. I went all over it — into the yards, where the women were sitting talking, their babies playing and running about in front of them — into the huge dining-room, where the evening meal of bread and cheese and tea was being laid out for the able-bodied paupers — into the children's playroom and the children's dormitories — into the dormitories of the able-bodied paupers, and of the aged and ailing paupers into the storeroom, the strong-room and padded room, the boardroom and committee-room — and I must say that I was extremely interested in and pleased with all that I saw. The people looked on the whole happy and contented enough. There were some women who seemed absorbed in their own thoughts, and whose faces wore a soured, half-angry expression; but such faces are to be seen wherever one may turn — in the most brilliant assemblage of wealthy and influential people, as here within the workhouse walls. As a rule, I repeat, the people appeared contented. The children were plump and active enough in the main. One or two whom I pointed out as looking sickly had been recently taken out of "the house" for a time by their parents, and had not yet recovered the effects of that outing. One little creature, who had just been brought back by its mother to the workhouse where it was born, was very pale and thin; its eyes were sunken, and its hair, of the splendid hue that friends call auburn and foes call red, formed a startling contrast to its white face. The child bent its head and clung to its nurse as I stopped to speak to it, and then the matron explained that it had only just come back, and that during its absence it had deteriorated at a startling rate. Poor little soul! It was preparing for a long journey, that must be taken once and that cannot be retraced; and there was something wistful and pathetic in the child's eyes that suggested an early solution to the trials and difficulties of its little life. Close at hand was a specimen of sturdy childhood that formed a curious contrast to the child in arms I have just described. "Jack" was as active as an eel — he was here, there, and everywhere; he was capering among the old women here, he was plunging into the children's nursery there; everyone seemed to know him and to have a kind word for him ; he hung on to the matron's skirt as she entered one ward, and turned to scamper after her as left it; he ran about beside me, looking up in my face, and smiling; he insisted on playing with my friend's umbrella. In fact, he was as healthy and active as anyone could wish; more active, in fact, than many persons would think desirable. I was glad to see the little fellow's activity, for it showed that the child was healthy, and his good spirts and merry face showed that he was happy.

The children are always my first preoccupation when I visit a place like this. I am always anxious that the children should be well looked after and should be happy. They are so totally irresponsible for their own position that it seems to me too much can hardly be done for those among them whose lots are cast in difficult and dreary places from no fault of their own. How true it is that, as Mrs. Browning says,

The child's sob in the silence curses deeper

Than the strong man in his wrath.

I should be glad to think that no children in England were worse off than the baby paupers in Chelsea Workhouse. I was inexpressibly glad, moreover, to see the little creatures clustering about the matron, and to see her behaviour towards them, indeed towards all the women as well. Everywhere the faces brightened as she approached; directly she appeared she was in instant request; here she was wanted to speak to a poor woman suffering from St. Vitus's dance; there she was wanted to exercise her judgment in the matter of some special permission. Wherever we went, there were eager eyes cast on Miss Sutton. whose help was needed, and whose kind words and cheering, friendly smiles were evidently treasured. I went into the old women's ward just as the tea was beginning, and there saw one of the great characters of the workhouse — an old lady of 98, who is the wife of a soldier, and who followed her husband through all the Peninsular war. She sat in an armchair by the fireplace, with a little table before her for her teacup and plate, and she looked for all the world like one of Herkomer's pictures of old women, in her high cap with its goffered frill, in her simple gown, the bodice of which was hidden by a red kerchief loosely crossed over her breast and tied behind. She had been all over Spain and Portugal and France, she told me; she was young and strong, she said, and so was her husband, but now it was all changed and then the tears came into her eyes, and she began to cry. She brightened up in a moment, however, when Miss Sutton talked to her, and was soon smiling again, her old face, enlivened by a pair of bright hazel eyes, being wonderfully expressive. I expect thaw hazel eyes of hers did a rare amount of mischief in their time, and were quite as potent in their way as her husband's weapons!

The numbers of dormitories I saw were, in common with every part of the establishment, faultlessly clean, and they are most carefully ventilated. There was no closeness in them in the daytime; that I can unhesitatingly declare. The beds were clean and comfortable and the red and yellow counterpanes gave a cheerful aspect to the rooms. The number of rooms I went through may be guessed when I tell my readers that 585 persons were sleeping in the workhouse the very night of my visit. Up and down, from east to west, from north to south, there are galleries upon galleries of beds, and everywhere the same care for cleanliness, the same rules for ventilation, the same order and discipline. The only difference made in the treatment of the paupers is that the old people receive all kinds of extra attentions and comforts that are not awarded to the able-bodied paupers.

There are various trades and occupations going on in the workhouse, of course, such as tailoring, woodcutting, laundrywork, &c., and there is a due amount of oakum picking. Then all the housework and needlework have to be executed, and here I lit upon a curious fact. When I was in the storeroom, and saw all the piles of material, made and unmade, of sheeting and skirting, of good strong Welsh flannel, and some serviceable prints for the dresses, I asked if the inmates of the workhouse made all these clothes and all the bed linen, &c. I was told that they did, and the master of the workhouse (Mr. Gibbons) — a kind-hearted man, utterly removed from the traditional master — added that he did not know what they should do when the present race of old women died out, for the young women of these days will not and cannot sew, he said. Nearly all the needlework of the establishment is done by the women, the young ones being unable to use their needle, and resenting any attempt at teaching them. This is significant, and indicative of the times! Each person within the walls has to work if possible in some way or other, and very long ago one initiate of the house, who was an artist fallen upon evil days, painted a picture, upon the dining-room wall, of Chelsea Church many, many years ago. The picture is a genuine curiosity. Above it is painted, on the wall, one eye of an enormous size, and the peculiarity of which is that from whatever part of the hall you look at it, it appears to be looking at you. The boardroom that I mentioned is the meeting-room of the Board of Guardians, and here well-known and prominent men of experience and standing congregate to attend to their duties. Sir Henry Gordon, who attends, was specially engaged at the time of the Crimean war to reorganise the supply of provisions to our army. It is a welcome feature in Sir Henry Gordon that he should be willing to devote his time and organising capacity to the small details of parish administration. In this room hung a portrait of Miss Sutton's father, who was for thirty-five years master of the workhouse, and Miss Sutton has held the post of matron for twenty years!

As we turned from the great of the workhouse I said to the friend who had accompanied me that if all workhouses were like that, if all masters and matrons were like those I had just seen, and who had shown themselves so obliging and had taken so much trouble, I could not bring myself to think the paupers so badly off. But my friend assured me that I had seen a palace among workhouses, and that few of the London institutions of the kind could rival the Chelsea house.

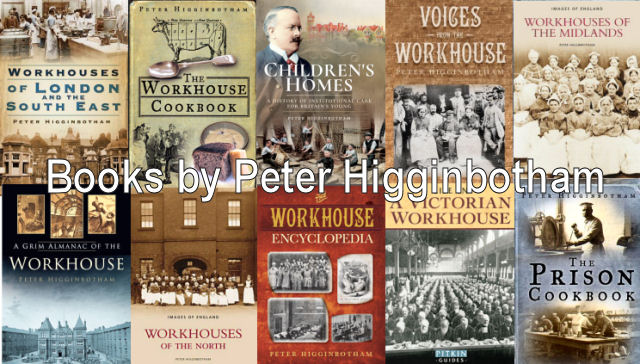

Unless otherwise indicated, this page () is copyright Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.