LIFE IN A LONDON WORKHOUSE

by Duncan Cumming

This account of a stay in the Strand Union workhouse at Edmonton was published in 1901.

It is not given to every one to realise by experience what parish relief actually means. The rich are content to believe it to be a wise provision of a beneficent nation for the comfort and well-being of its poor, while those for whom it is intended look upon it with such horror and loathing as occasionally to die of starvation rather than avail themselves of its benefits. The latter view arises from regrettable ignorance and prejudice, for even the average workhouse enables a man to live a cleanly life, while a well-ordered institution, such as that in which my circumstances compelled me to take refuge for a time, is quite unlike the popular idea of the workhouse. On that bleak January afternoon when, my last sixpence gone, I found myself destitute and friendless in the streets of London, I knew no more about the workhouse than that whenever I had heard it mentioned it was with the sneer of contemptuous pity. And now when I found myself face to face with dire poverty, I shrank from getting closer to it. At last, after wandering aimlessly about the streets for a whole miserable afternoon, a friendly police-serjeant whom I accosted encouraged me to make my way to the door of the relieving office, where he left me with the words :

"You go in now, and get admitted. You can live a cleanly life there till you have time to pull yourself together. Answer all their questions plain and truthful, and don't mind their bluff, they have to be on their guard against frauds and loafers. Good-day, and good luck to you."

With those encouraging words he left me at the door of the relieving office of the Strand Union, in Maiden Lane. On entering, I was confronted by a stern-faced gentleman, who asked me, in succession, a number of questions, and finally, in a hesitating manner, handed me an order for admittance. The workhouse of the Strand Union is situated in Edmonton, some ten miles north of London, and thither I was conveyed with about a dozen others, men and women, in a large closed van, driven by a uniformed official.

Some of the women, who had been taking on quantities of their favourite "four ile" after getting their orders, began to sing and weep when we were well on our way ; they kissed and sympathised with each other, and finally fell to quarrelling in a pompous, subdued fashion, which dwindled down to an air of cowed submission when we reached our destination.

At the gate or receiving ward, we males were bathed, and received each a clumsy, ill-fitting suit of corduroys. This was but a temporary garb, however, for I may mention here that no one at this institution is condemned to permanent corduroys except the young able-bodied men on task-work. In a day or two afterwards, when I was "put on a job," I was supplied with a good suit of ordinary citizen's clothes, the male inmates of the Strand Union Workhouse wearing no uniform, but being provided with clothing as varied in colour and cut as that worn by the people in the streets.

While we were eating our supper of tea, bread and butter, the house doctor came in, and looking us over with rapid, scrutinising glance, asked each of us in turn, "Are you all right?" Supper over, we were dismissed to our several dormitories, a pasteboard card, inscribed with the name of each man and of the ward and bed number, enabling us easily to find our way to our respective quarters. Crossing the space between the lodge and the main house, I came to a long corridor leading to a flight of stone stairs, which I ascended as far as the second storey, where my particular ward or dormitory was located. Figure to yourself a long, many-windowed apartment, painted in vivid green and brown colours, with two square chimney shafts at some distance apart along the middle of the room, which had two great roaring fires on each side of them ; and four rows of beds running from end to end, with two wide matted passages separating the outer from the inner rows, the whole gleaming in the light of the bright fires below and of the gas jets overhead, and you have an outline of the strange scene that greeted my eyes as I entered the place which was to give me nightly shelter for many months to come.

There were nearly eighty men of all ages, from youth to decrepit old age, in this large dormitory, some already in bed, others leisurely shaking down their mattresses, and others standing chatting round the big fires. The bed itself was a very good one, a flock mattress, with two white sheets, two pillows, three heavy blankets, and a brown counter-pane. Everything was fresh and clean, for cleanliness is the dominant note of work-house life. Opening off this dormitory there were two lavatories, with hot and cold water taps, bath, roller towels, and every other convenience. At 8 P.M. the retiring bell clanged loudly outside, and in another quarter of an hour the wardsman turned off the gas, leaving, however, a safety lamp hanging at each end of the room to afford a dim light during the night. Some desultory talk was carried on here and there till nine o'clock, when all became still, and it became the wardsman's duty to see that silence was preserved after that hour ; and in case of serious disturbance he had only to touch an electric button in the wall beside his bed to receive assistance from the night-watch on duty in the regions below.

The rising bell woke me up smartly next morning at 6.45 A.M., breakfast was served at 7.30, and at 9, the daily office hour, I and the other "fresh admissions" were brought before the master to answer a few stereotyped questions, after which we were handed over to the tender mercies of the labour-master. This official has usually a difficult course to steer, and in a free-and-easy community like the inmates of this workhouse — largely composed of men of Hibernian extraction — particularly so. In the present case he was a very tall young North-countryman, who, having a will of his own and standing squarely on the prerogatives of his office, evidently made it his aim to treat every inmate alike, without partiality or prejudice. After a momentary glance at me he ordered me to go and report myself to the laundress. This female officer, whom I found to be a buxom, alert-looking, middle-aged person, clad neatly in nurse's costume, after eyeing me over critically, set me at once to work vis-à-vis with an exceedingly lively and active grey-bearded septuagenarian, at the sliding drying-horses with which the laundry was fitted. The laundress, I soon came to know, had the reputation of being a choleric and tyrannical personage among the men and women, about thirty in all, under her orders, but during the four months I worked under her I saw nothing to justify such a reputation. It is true that her manner was at times abrupt and scathing to the careless or the idlers, but she was by no means ill-natured at bottom. She had a good deal to try her patience : in charge of the washing for over one thousand inmates, as well as for the officers and the master's family — washing that must, at all hazards, be ready at the appointed hour — she could never count with certainty from day to day on the services of her most efficient hands, who, whenever the chance of outside work presented itself, naturally took their discharge.

One of the anomalies of workhouse life is that all the male inmates up to sixty years of age are booked as "young men," and so are liable to be assigned to "task-work," at the discretion of the doctor or the master. Now this same task-work is worthy of brief notice, inasmuch as the regulations concerning it are carried out to the letter in many workhouses, and in these life can hardly be worth living for most of the able-bodied men who are so unlucky as to fall short, if only by a few weeks, of the arbitrary age-limit of 60 years. These regulations, issued by the Board of Guardians, are posted up on the walls of the inmates' day-rooms and read as follows : "The task-work indoors required to be done under the superintendence of the labour-master by able-bodied males under 60 years of age, in return for their food, clothing, and lodging, is to break from 5 to 10 cwts. of stone per day, at the discretion of the master, or, to pick not less than 4 lbs. of unbeaten oakum. Able - bodied males and females over 6o years of age to be put to such work as the medical officer may sanction, according to their capacity and strength."

There was very little stone-breaking or oakum-picking going on at this institution while I was there, and that little fell into the hands of the right persons, sturdy young fellows who had no business to be in the workhouse, and whom a tolerably stiff application of this kind of pressure was usually successful in driving away. But there was plenty of other kinds of work, and almost everybody had something to do. The impression seems to prevail that the workhouse is the paradise of the idle and lazy, and that when an inmate has reached an advanced age, or has lost an arm or a leg, he is thereby exempted from labour. Never was there a greater mistake. Almost everybody (and the exceptions are doctor's cases) that can stand on two legs or on one, or who can see with one good eye or with two bad ones, has to do some kind of work in the workhouse, which, in fact, well deserves its name.

Setting aside the task-work already mentioned, workhouse labour is divided as follows : Field-work and gardening, conducted under the supervision of a special officer, and at which men used to outside work are chiefly employed ; and, secondly, domestic work — the kitchen, bakery, dining-hall, laundry, sick wards, artisan shops, and the stairs, passages and windows. During my sojourn at "the Strand," work seemed to go on just as at some well-ordered factory or commercial house, without any friction or petty tyranny, for the master himself, a humane and considerate gentleman, abhorred fussiness or injustice in a subordinate, and though there were one or two officers of the bumptious, Bumble-minded type who would have doubtless preferred a more arbitrary regime, they were constrained, willy-nilly, to follow the lines laid out by their chief. I worked not only in the laundry, but also, in turn, as attendant in a sick ward, as waiter and cleaner in the dining-hall, and as assistant cook, and in no case did I ever find the yoke a galling one, though the monotony of it made it often tiresome enough.

During leisure hours the men dispersed to their various day-rooms, of which there were six, including a comfortable reading-room, with wall pictures, and tables well supplied with old magazines and illustrated papers. There was also a library, from which books were issued twice a week, but these also consisted only of bound volumes of old magazines, and a few defunct three-volume novels of aristocratic flavour. There was not a poet, or a historian, or a scientist, or a standard novelist represented in the whole collection.

All labour was over by 5 P.M., most of it much earlier, and after tea, which was served shortly after that hour, we were our own masters till bed-time, which was eight o'clock all the year round. The dormitories, however, were thrown open immediately after tea-time, and anybody who chose could retire then. Many availed themselves of the opportunity, and often have I heard some worn-out old fellow murmur, as he carefully made down his bed for the night, "Thank God for this bed I It is the best thing in the house." For myself, when work was over, and I had been somewhat refreshed by the large bowl of hot tea served with the evening meal, I was glad of the solace of a book and a pipe, seated in some corner amid a babel of voices, before retiring to rest. Sunday was the day when I felt most depressed in spirits, for then I had time to realise most acutely the blank hopelessness of my position. There was a tidy little chapel at which Anglican services were held twice on Sundays and once during the week, the Roman Catholics being accommodated in one of the larger day-rooms. Presbyterian though I am, I joined the worshippers in the chapel pretty regularly, though I could never rid myself of the painful feelings caused by the sight of the poor old women on the left of the aisle, in white caps and blue striped cotton dresses, with their wan sad faces mutely speaking in unavailing protest against the pitiable lot of their declining years.

Three times a day, at the tolling of a bell, we all flocked to the common dining-hall, a long and rather bleak-looking apartment, one end of which was reserved for the female inmates, who entered from their own quarters by a separate door. Leaving out the gruel, or "skilly" table, occupied by the few task-men in corduroys, breakfast and supper invariably consisted of a pint of tea, with a six ounce loaf of white bread and a pat of margarine. Dinner consisted, for all on Sunday, of five ounces of boiled beef, with half a pound of potatoes, or, rarely, cabbage or parsnips ; on Monday, the men on the labour side had this diet repeated, while those excused from work or employed only on light labour were served with four ounces of bread and a pint of pea-soup, the latter more or less thickened with vegetables and scraps of meat; on Tuesday, boiled bacon and cabbage for all ; on Wednesday, Irish stew, a humorous libel on that well-known dish, for it consisted only of a thin potato-soup, with a few cubes of tough and desiccated beef floating in it — it was, in fact, the least satisfactory dinner in the whole week's menu ; on Friday, baked fish and potatoes, a dinner from which, though, as a rule, it was good in quality and abundant in quantity, many of the inmates unaccountably absented themselves ; on Saturday, the labour men dined as on Monday, while the others were regaled on a kind of suet pudding, with molasses sauce, which when served hot enough was palatable and nutritious. It must be confessed that in this diet the beef was sometimes very tough and horny ; the Tuesday bacon — the dinner the inmates seemed to like best of all — was often insufficiently cooked, as were often, also, the whole potatoes (when there were any) in the so-called Irish stew ; and that the bread sometimes came in either over-baked or carelessly kneaded. But, on the whole, the diet was a fairly sufficient and nourishing one, and for those whose appetites it did not satisfy there was always plenty of left-over bread knocking about with which they could make good the deficiency.

All men on labour were allowed by the Guardians an extra two ounces of tea and half a pound of sugar per week, which was served out to them every Saturday afternoon in brown paper bags, in the dining-hall, and as there was a stock of kettles and tea-pots in the different day-rooms, a man could brew himself a mug of tea whenever he wanted it. Further, all men over sixty, and younger men on responsible or skilled work, received an ounce of shag tobacco every week ; while inmates in charge of shops, such as the tailor, the shoemaker, and a few others, drew special rations and a pint of beer daily, and they were understood also to be in receipt of a small weekly pittance of money (2s. 6d.).

On my first Friday in "the house," I was summoned with others before the weekly committee of the Board of Guardians, and, after answering a few questions, told I might remain for a month, at the end of which time, if I had not meanwhile taken my discharge, I was to present myself again before them. Still another ordeal had to be gone through before I could consider myself a bona fide inmate. One evening, after tea, I was sent for by the "pass-master," name of ill omen to him who, on his admission, has not given a truthful account of his antecedents. This official, in the present instance, was a gentleman of suave and insinuating address, who after courteously bidding me to be seated near him, began to talk to me in the tone of one's family solicitor pleasantly breaking to his client the news of some unexpected windfall of fortune. The pass-master is the ratepayer's watch-dog, for his duty it is, by judicious wheedling and skilful cross-questioning, to discover whether a new-corner has any claims to the shelter of the Union, and to pass on interlopers either to their native parishes or to those in which they have been in continued residence for a period of three years or more.

There are all sorts of people to be met with in a large workhouse like that of the Strand Union. Besides the ordinary day-labourer and street-hawker, you may find among the crowd that throngs the day-rooms at night, walking about in listless vacuity, or sitting at the long tables reading or playing at draughts — decayed actors, journalists, lawyers, many old soldiers and a few sailors, commercial men, yes and, I grieve to say it, a broken-down clergyman or two. The rough and foul-mouthed graduate of the slums is also to be met there, especially during the winter months, but his life is not made too easy for him, and when he would disport himself in his natural choice way, he is promptly extinguished by the better element around him, always in preponderance even in such a society as this of the workhouse. But these young roughs do not stay long ; a diet of gruel, with the hardest work thrown in, is not to their taste, and as soon as they think they have been in the "lump" (as they term the workhouse) long enough to warrant them in asking the master for a coat or a pair of trousers, or, more often, a pair of shoes, they quickly take their flight back to their London rookeries. If the Local Government Board took away from the younger men who thus make a convenience of the workhouse the absurd privilege of taking their discharge after giving twenty-four hours' notice, to return the very same day if they like, there would not be such a run on its resources, at times, by the young victims of improvidence and drink.

Drink! The word suggests another and more painful reflection. Men over sixty are allowed to go out every other Wednesday, from 1 P.M. to 8 P.M. On any other day but that one would be inclined to infer from their bearing and conversation that not their fault but their misfortune was responsible for their incarceration, in their declining years, in the pauper's prison-house. But the eagerness with which they rush out with the few shillings sent to them periodically by poor, kind-hearted friends outside, to squander them noisily over the dingy, greasy bars of the neighbouring public-houses, and the maudlin, semi-imbecile condition in which many of them return at night, tell all too plain a story of the influence that strong drink has wielded over their past lives. There are, doubtless, many exceptions, but that drink has been one of the most potent factors in the evolution of the workhouse pauper, who that is thoroughly acquainted with him can deny?

Life in a London Workhouse by Duncan Cumming was published in Good Words in 1901.

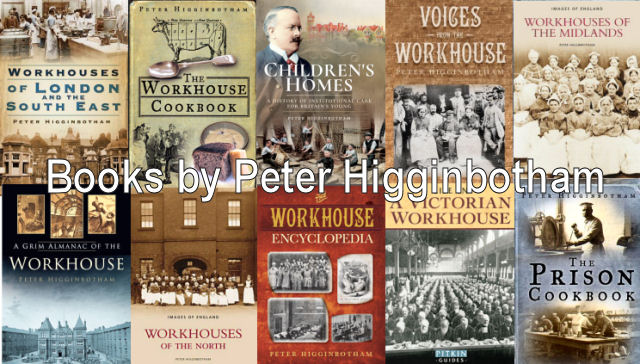

Unless otherwise indicated, this page () is copyright Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.